The slip-up in the Liberals’ biggest policy promise

The details of duelling $6-billion tax pledges from Trudeau and Scheer deserve a closer look, including one not-insignificant omission

Trudeau makes a campaign stop at a daycare in St. John’s, Nfld., on Sept. 17, 2019 (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick)

Share

Entering the home stretch of this fall’s federal election race, the reviews have turned decidedly sour. The contest is, leading pundits tell us, about nothing—a deeply unserious affair in which any big noise is set off only by revelations about the leaders, some of them undeniably grabby, but which don’t have much to do with how the country is actually run.

Yet both the governing Liberals and the Conservatives, who of course stand the best chance of bumping them from power, have each put at least one big-ticket tax proposal in the window. These directly competing promises of broad tax relief, either of which would cost billions to implement, haven’t attracted much scrutiny, even though they’re designed to appeal to wide swaths of Canadian families.

One reason the tax pledges have drawn scant notice is that they’re superficially so similar they might seem to cancel each other out. The Liberals propose to raise the “basic personal amount” (BPA)—what an individual can earn before income tax kicks in—to $15,000 from around $13,000. The Conservatives counter with a promise cut the tax rate on the lowest income bracket—up to $47,630—to 13.75 per cent from 15 per cent.

Either change would see taxpayers sending nearly $6 billion less to Ottawa when the policies are fully implemented. The contrast gets a lot more interesting, though, when you probe beneath those top-line numbers. Arguably the key difference is that the Liberal proposal would be far more advantageous to many single-income families, while the Conservative option would be better for many two-income families.

Under the existing BPA rules, the working parent in a one-income family claims the full BPA plus an equal amount for a spouse who doesn’t have any or much income. In the case of a single-parent family, the parent claims the BPA plus an equal amount for one child or another eligible dependent. That means the $2,000 increase in the BPA promised by the Liberals would really be double that amount for single-income families.

READ MORE: A 338Canada projection: Have the Tories blown it in Quebec?

There’s an unexpected wrinkle here, though. In looking into this part of the Liberal plan, Maclean’s discovered that the Liberals failed to explain this intended feature of their proposal to the Parliamentary Budget Officer, when the PBO was independently costing their BPA platform plank.

So the PBO’s calculations assumed that the Liberals did not intend to raise the credit for a dependent spouse or child. Just to add to the confusion, University of British Columbia economist Kevin Milligan, who was asked by the Liberals to analyze the policy’s impact in advance of its release, assumed those credits would increase in line with the BPA.

The result is that the PBO’s estimate of the cost of the Liberal plan, about $5.7 billion by 2023, is low by about $490 million, according to David Macdonald, a senior economist at the Ottawa-based Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. A Liberal spokesman confirmed that the party does plan to raise those closely related credits when the BPA increases, and that the PBO’s costing didn’t take that into account. After Maclean’s published this story, Liberal party officials responded by stressing that there will be enough flexibility when the tax measures are designed and implemented to keep those added costs well below the $490 million it would take to raise the credits fully in line with the increased BPA.

It is odd, to say the least, that the biggest single promise in the Liberal platform, in terms of its bottom-line impact on the federal books, is not precisely costed out. Still, the omission in the PBO costing amounts to less than nine per cent of the total promise, and thus doesn’t much change the comparison between the Liberal policy and the Conservative alternative.

Every chance they get, the Liberals frame that choice in starkly partisan terms. They say the Conservative proposal would cut taxes more for a person making $400,000 than for someone earning $40,000. “Whenever the Conservatives cut taxes, they cut them for the wealthy, and in this election, it’s no different,” Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau says in a campaign ad. “The Conservative approach would go back to giving tax breaks to millionaires.”

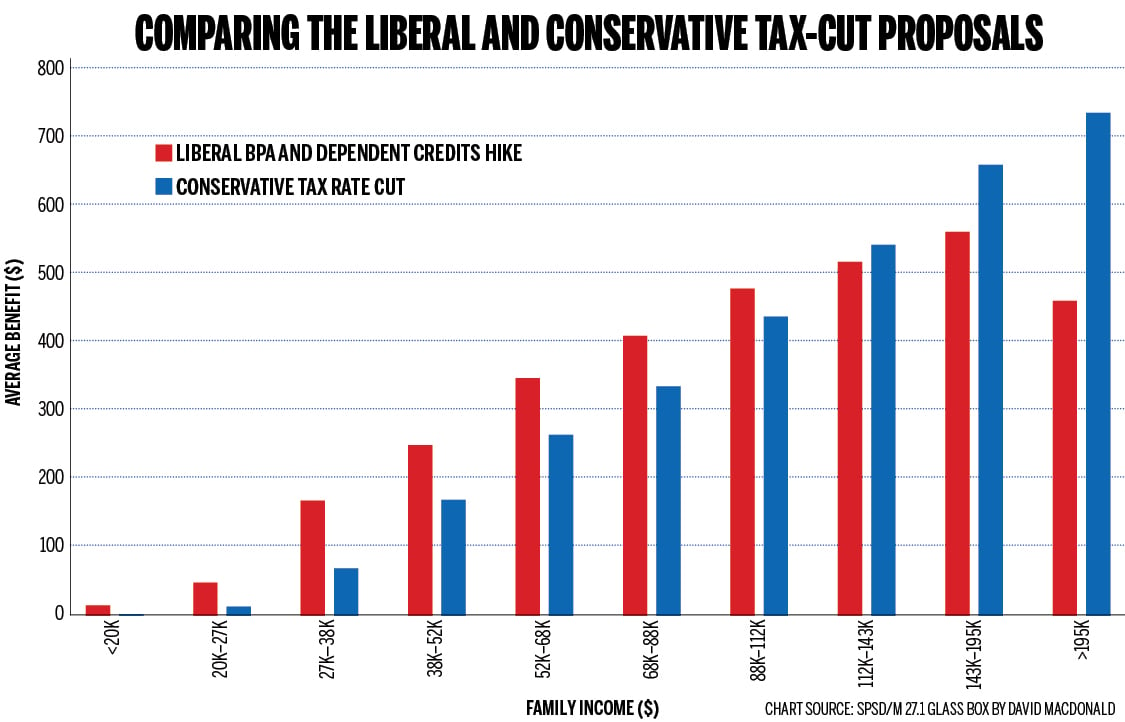

In fact, the contrast isn’t nearly that straightforward. Macdonald crunched the numbers for Maclean’s. Dividing families into 10 income groups, called deciles, he found that the Liberal plan on average gives families a larger benefit up to those earning in the $88,000-$112,000 range. In the deciles above that level, the Conservative tax cut on average translates into bigger tax savings.

One reason for the Conservative proposal being better at the top end of the income scale is that the Liberal plan doesn’t extend the BPA increase to those earning more than $147,000. But Macdonald said that limit matters to very few taxpayers. “The Liberal version has a phase-out, but that phase-out is so high—it starts at the top two per cent of individuals—that it doesn’t have a huge impact,” he said.

In fact, Macdonald said the Liberal policy—just like the Conservative alternative—tends to offer rising tax benefits as families climb the income ladder. “Generally,” Macdonald said, “it doesn’t seem that either is particularly progressive, with high-end families gaining as much, if not more, than middle- and certainly lower-income families.”

But the two proposals are far from interchangeable. There are big differences when it comes to single-income and two-income households. Trevor Tombe, a University of Calgary economics professor, looked at that point of contrast for Maclean’s, although he cautioned that his estimates don’t take into account all sorts of credits and deductions that can change how much tax Canadians actually pay.

Still, Tombe’s estimates give a sense of the gap between the real-world impacts of these clashing tax-relief pitches. Consider the median lone-parent family, which Statistics Canada says made $46,140 in 2017. Tombe said a single-income taxpayer making $40,000 who has a spouse or other dependent would be ahead by $581 a year with the Liberal BPA increase, compared to only $173 with the Conservative tax-rate reduction.

But the picture is different for two-income families. Statistics Canada says the median couple family earned $92,990 in 2017. Under the Liberal proposal, a two-earner family making $80,000 would be $581 better off, Tombe said. But under the Tory proposal, that family’s tax saving, assuming equal incomes, would be $673, he said. Raise that two-income family’s income to $100,000, and the Conservative cut saves them $923, while the Liberal cut is still $581.

In other words, according to Tombe, the Liberal BPA increase is more generous for single-earner families earning about the median income (that mythic middle-of-the-pack point at which half of all Canadian families earn less, half more), but for a two-income household around the median, the Conservative policy looks quite a bit better.

Neither the Liberals nor the Tories have said they intended to design tax policies that would help families differently depending on whether they have one or two incomes. That appears to be an unintended consequence of what they’ve proposed. “It does point out,” said UBC’s Milligan, “that these kinds of family tax issues can involve some subtleties, and you have to pay attention to implementation to get it where you want to go.”

Macdonald is critical of both the Liberal and Conservative approaches. “The challenge with monkeying around with these broad taxation levers is that you always end up with these sorts of distributions,” he said. “Also, you likely get little political credit for it, compared to something more tangible like say a new transfer program or a new social program.” However, he does credit the Liberal plan for offering more to the lowest-earning third of families and unattached individuals.

Not everyone stands to gain no matter which party wins—not even close. According to Macdonald, about a quarter of all families stand to reap no tax savings at all from the Liberal or Conservative policies. Who misses out? “You’ve got a single mom that receives social assistance and the Canada Child Benefit,” he said as an example. “Neither is taxable, so she can’t benefit from these changes.”

The nuances that Macdonald and Milligan point to haven’t even been hinted at in the campaign debate. In fact, almost no serious discussion at all has been prompted by these promises. Enough time still remains, though, for that to change as the race lurches into its final week and a half. But if this keeps on feeling like an election about nothing, that will mean duelling $6-billion tax pledges—among other mostly overlooked platform commitments—didn’t count.