Trial by fire: An exclusive excerpt from Thomas Mulcair’s memoir

Tom Mulcair was a lonely federalist working for the Quebec civil service in 1980, when a referendum threatened to tear the country apart

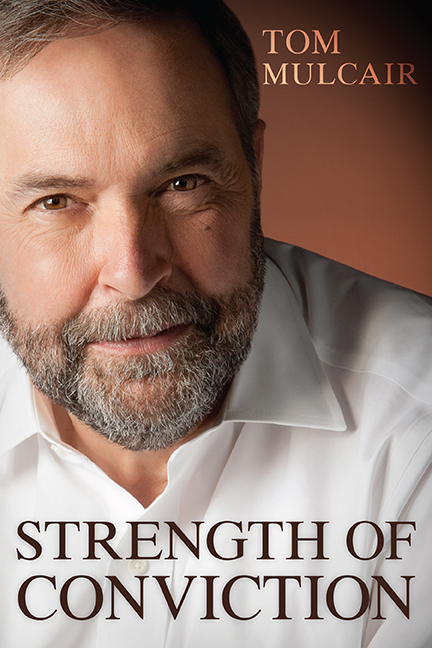

NDP leader Tom Mulcair speaks at a rally in Ottawa on June 17, 2015. The federal NDP is going on a pre-election offensive aimed at demonstrating it’s the party best positioned to defeat Stephen Harper’s Conservatives in the looming Oct. 19 election. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Justin Tang

Share

As the 1970s came to an end in Quebec, the Parti Québécois was in government, René Lévesque was premier and Thomas Mulcair, fresh out of law school, was a twentysomething in the provincial Justice department. In 1980, he was moved to the Conseil de la langue française, a body established to advise the government on the application of Bill 101, the province’s French language charter. As the first Quebec referendum loomed, Mulcair would find himself drawn into that political fight. Strength of Conviction, his new memoir, is Mulcair’s attempt to explain himself and how he got to where he is now—leader of the NDP, with decent odds of being this country’s next prime minister.

As the 1970s came to an end in Quebec, the Parti Québécois was in government, René Lévesque was premier and Thomas Mulcair, fresh out of law school, was a twentysomething in the provincial Justice department. In 1980, he was moved to the Conseil de la langue française, a body established to advise the government on the application of Bill 101, the province’s French language charter. As the first Quebec referendum loomed, Mulcair would find himself drawn into that political fight. Strength of Conviction, his new memoir, is Mulcair’s attempt to explain himself and how he got to where he is now—leader of the NDP, with decent odds of being this country’s next prime minister.

When I say that for me, getting a job at the Québec Justice Department was like being sent to an exclusive finishing school, I mean that, having gone to McGill so young, I may have been able to catch up and get through law school, but the Québec Justice Department is where I actually learned the law. I loved my job, so much that in 1980 I applied for a permanent position in the civil service, because I wanted to be hired right where I was, at Justice. You had to put in your name to get on the list of candidates, and then to qualify by passing the exams. I finished first, which meant that my name was first on the list for all departments, and I found myself “drafted” by the Conseil de la langue française, an advisory body created by the Lévesque government under Bill 101, the Charter of the French Language. Not to be confused with the Office de la langue française, which supervised the application and enforcement of Bill 101, the Conseil had as its mission to counsel the minister responsible for the application of the Charter of the French Language on any question relative to the French language in Québec.

At the time, the political context in Québec was dramatically different from what it is today. By the early 1970s the language issue had reached full boil. The October Crisis had terrified the province. The invocation of the War Measures Act, giving the army and police extraordinary powers that led to the arbitrary arrest and detention, without charge, of hundreds of innocent people, inflamed the cleavages already dividing the population. The Parti Québécois victory in the election of 1976 had stunned everyone, and as a lawyer in the legislative drafting branch of the Québec Justice Department I had a front-row seat on the projet de société being presented to Québecers during the first Parti Québécois mandate. In social, economic, and environmental terms, René Lévesque and his government came in on a whirlwind of change, often inspired by the Scandinavian social democratic model. Progressive policies were enacted, among them the Québec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, a university tuition freeze, public no-fault auto insurance, anti-scab legislation, government regulation of the professions, and the beginnings of publicly subsidized child care.

The modèle québécois (Québec approach) that evolved at that time would become emblematic of forward-looking policies that reflect Canadian values of fairness and solidarity. As a progressive, I was truly impressed by the speed and efficiency with which Lévesque and his government were able to effect real change in people’s lives. But his was also a government that was preparing to hold a referendum on dismantling Canada. As a Canadian, therefore, I felt a more and more pressing need to get involved and do everything I could to help keep our country together. Up to that point I had never engaged in grassroots political organizing. The biggest campaign I’d ever participated in was my run for president of the Law Undergraduate Society at McGill. I was a 25-year-old husband and dad, working full-time in government, and had no idea how to get started. I learned then the truth of the adage attributed to Tip O’Neill, the former Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, that “all politics is local.”

Related: Q&A: Thomas Mulcair on why Canada may be ready for the NDP

In Québec, as the referendum approached, sovereignist fervour was at its peak. It was also true in our department. In 1980 I’d come across precisely two other federalists at Justice. One was very crafty about hiding it; the other was Pierre Gauthier, who, like me, is not crafty at all and wore his Canadian heart on his sleeve. I would soon find out that there were many more of us than met the eye. Pierre, a former chief of staff to a minister in the first [Robert] Bourassa government, was a senior administrator in the department. He and his family, like Catherine, Matt and I, lived in Cap-Rouge. Pierre was very actively involved in organizing for the “No” side in the Québec City region. Pierre got me involved in getting people out to rallies, canvassing to locate potential “No” supporters, and other campaign-related activities. It was my first real taste of political organizing, and his depth of experience taught me a lot. The usual ban on political activity by civil servants (in force before the Charter ended the ban) had been lifted by the PQ government for the referendum. Our next-door neighbour in Cap-Rouge, Claude Beausoleil, was also deeply involved in organizing, and through him I learned another important lesson: that participating meant a lot more than the old cliché about smoke-filled back rooms.You could hand out flyers. You could talk with your neighbours. I was amazed at how many of the people I spoke to planned to vote No in Québec City.

Meanwhile, within the civil service, known federalists were subject to teasing or to persistent attempts at “persuasion,” which to some must have felt like intimidation. Others just kept their heads down. Not me. One day, an enterprising lawyer colleague, knowing that I planned to vote No, asked to have lunch with me, thinking he could beat it out of me during the course of the meal. Our deputy minister, René Dussault, was sitting right next to us in the cafeteria and couldn’t help chuckling as he overheard our discussion, which must have sounded like something straight out of a re-education program. In fact, in the months leading up to the referendum the atmosphere was difficult, and the cleavages it opened in the workplace, within families, and even between people who until then had been lifelong friends took many years to heal.

For me, the defining moment of the campaign was hearing Claude Ryan, the leader of the Québec Liberal Party, give a speech in a packed hall in Val-Bélair, a northern suburb of Québec City. As the director of Le Devoir he’d been Québec’s leading public intellectual, writing immensely influential editorials and becoming known as “le pape de la rue Saint-Sacrement” (“the pope of the rue Saint-Sacrement,” after the street in Old Montréal where the offices of Le Devoir were situated). In 1978, he’d left the paper to run for the leadership of the Liberal party. Now here he was, campaigning flat out for Canada. He had no voice left, but he was awe-inspiring. He took the referendum so much to heart that on the night of the vote, after the results were announced and showed a resounding 60 per cent to 40 per cent victory for our side, he went on hectoring his opponents. It left him with an image problem that unfortunately stuck, but was at odds with the kind, caring, principled man that he was.

The PQ government had lost decisively, and many who had supported the “Yes” side, including within the government, were hurting and bitter over the defeat. Within the civil service there were consequences. Québec City is a civil service town. Obviously, a great many government employees had voted No. Blaming them for the “Yes” side’s loss in the provincial capital, the premier and his cabinet spun around and trained their sights on the miscreants. As for me, in September I obtained my titularisation—that is, a permanent appointment to the civil service —and in the spring I was elected secrétaire de section (section head) of the Syndicat des professionnels du Gouvernement du Québec (SPGQ), the Québec union of public service professionals and the second biggest union in the Québec government. I would have a front-row seat as the re-elected PQ government started tearing up collective agreements.

When I got the call that I had been recruited into the Conseil de la langue française, I thought it must have been a mistake. A federalist, whose first language was English, at the heart of the advisory body reporting directly to the minister responsible for protecting and promoting the French language? When I sat down with Georges Rochon, the director of legal affairs, I got straight to the point. “You’re probably as thrilled to have me as I am to be sitting here, so maybe we can just move this along and I can apply to some other department,” I said. To my surprise, Rochon, who turned out to be the most generous guy you’d ever want to meet, replied: “Monsieur Mulcair, au contraire. J’aimerais tellement que vous veniez travailler avec nous” (“Mr. Mulcair, on the contrary. I would love it if you would come and work with us”). When I asked him why, he said it was because in his shop everybody thought the same way, whereas he believed that people needed to realize that sometimes having another point of view was healthy and useful. He reiterated how pleased he would be if I accepted the offer, so I did, working under Camille Laurin, the minister of cultural development and author of Bill 101, the 1977 law that established French as the language of work and as the sole official language in the province.

Excerpted from Strength of Conviction by Tom Mulcair. ©2015, Tom Mulcair. All rights reserved. Published by Dundurn Press