Trudeau’s incredibly close election battle—in 1972

Pierre Trudeau’s biographer talks about how Justin Trudeau’s second campaign looks remarkably like his father’s sophomore run

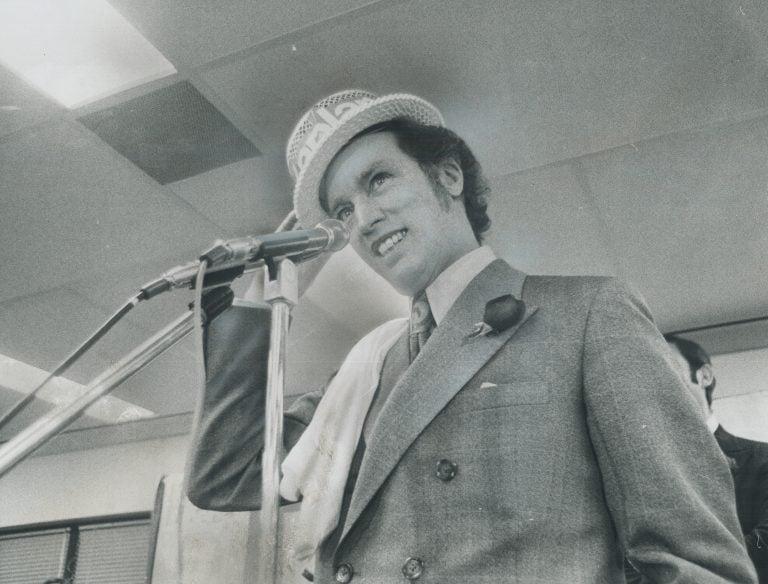

Pierre Trudeau dons a straw boater during a rally in Hamilton, Ont., in 1972 (Boris Spremo/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Share

There’s no need to resort to pointing out that Oct. 18 is the hundredth anniversary of Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s birth to bring the late prime minister into the mix of commentary on the excruciatingly close election battle his first-born son now finds himself waging.

Even without such an auspicious date to mark, the elder Trudeau’s saga—specifically the chapter on his rocky second federal election run as Liberal leader—just can’t be ignored. That 1972 campaign was fought to a virtual draw between his Liberals and Robert Stanfield’s Conservatives, leaving a chastened Trudeau relying on NDP support in order to remain to power with a minority government.

It’s hardly necessary to remark that there’s an echo in the air. If Justin Trudeau is reduced to an NDP-backed minority on Oct. 21, he’ll have been knocked down a peg from his surprise 2015 majority triumph in a way that’s uncannily similar to how his father was proved to be a mere mortal only four years after his storied “Trudeaumania” victory in 1968.

Let me pause here to say this is usually the point where a diligent journalist, having revelled in some convenient historical analogy, brings in the voice of a more sober professional historian to show why any superficial similarities matter far less than the deeper ways that past and present simply refuse to line up so neatly.

And, following proper practice, I indeed called up John English, director of the Bill Graham Centre for Contemporary International History at University of Toronto’s Monk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, and author of a magisterial two-volume Pierre Trudeau biography, to set me straight.

But English instead repeatedly pointed out parallels between 1972 and 2019 that hadn’t even dawned on me.

Let’s start with a key point of contrast, though. Both Pierre in ’72 and Justin in ’19 have faced criticism for how they behaved as rookie prime ministers and how they campaigned on their second times out as party leader. “The difference,” English says, “is that Pierre was seen as being distant, aloof and overconfident, but he was not seen, to use the words of Donald Trump about Justin, ‘weak and dishonest,’ or, to use the words of Andrew Scheer, ‘a phoney and a fraud’. Things are so much more nasty now. Bob Stanfield was such a gentleman, he would never have used words like those.”

READ MORE: Innovative Research poll: Who wants a minority government? Lots of Liberals.

Still, it’s not like politics in ’72 entirely lacked edge. For example, David Lewis, the NDP leader, gained momentum by running against what he called “corporate welfare bums.” And English detects the same thrust in NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh’s campaign-trail rhetoric, replete as it is with vows to end the way both Liberals and Conservatives have run Ottawa to the advantage of business. “They’ve been working to make life easier for the multi-billionaires. They get massive corporate tax cuts. Billions of dollars go towards them. We see offshore tax havens continue. This is not the way to build a country,” Singh has said.

Pierre Trudeau adjusted himself accordingly to secure Lewis’s support during his 1972-74 minority. “He shifted rather dramatically to the left and relied on the NDP, and, in that respect, the same kind of scenario is a distinct possibility,” English says of a possible Justin Trudeau-led, Singh-supported minority. “History does repeat itself, I guess, in some ways.”

And he pointed to two important ways that the broader context in 1972 looks strikingly like the 2019 conditions in which a minority Justin Trudeau government would govern—if that’s where this unpredictably tight contest ends, and that’s a massive if that Scheer’s Conservatives are working feverishly to stop from coming to pass.

Firstly, there’s tension between Ottawa and Edmonton over energy policy—a growing strain in ’72 as Pierre Trudeau faced Peter Lougheed’s muscular Conservative government in Alberta, and a major factor once more with Premier Jason Kenney running the oil-patch province now.

Secondly, there’s overwhelming unease over the U.S. presidency, always a key concern for a Canadian PM. “They had [Richard] Nixon and now we have Trump,” English says, adding, again: “The parallels are surprisingly strong.”

But before we get to finding how a minority might govern, and to seeing how it handles the external pressures under which it will take shape, there is the matter of votes to count. Today’s polls and seat projections show a clinch between Trudeau and Scheer that could hardly be closer.

Philippe Fournier of 338Canada has the latest data putting the two big parties in a deadlock at just over 30 per cent each in the polls, which might translate, if those support levels hold until election day, into roughly 132 seats for either. That would leave Trudeau or Scheer searching for some combination of Green, NDP or Bloc Quebecois support to secure the 170 votes needed to win a confidence vote in the House.

Nobody knows, of course, how the votes will tally up on election night. An enormous amount can happen in the minds of voters over the last weekend of a campaign. However it turns out, though, the tolerances can hardly be finer than in ’72. The initial count then was 109 seats for Stanfield’s Tories, 107 for Trudeau’s Liberals. Then there was a recount in a rural riding near Toronto. It switched from Conservative to Liberal—by a margin of four votes.

Four. And English notes that he found out to his amazement, when he was researching the second volume of his Trudeau biography, Just Watch Me: The Life of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, 1968-2000, that the Conservatives didn’t remember to send a scrutineer to oversee that crucial recount. Should there be recounts this time, don’t look for history to repeat itself on that score.