Who gets to be Canadian?

A veiled Muslim? A native-born terrorist? How the campaign is distorting the true meaning of citizenship.

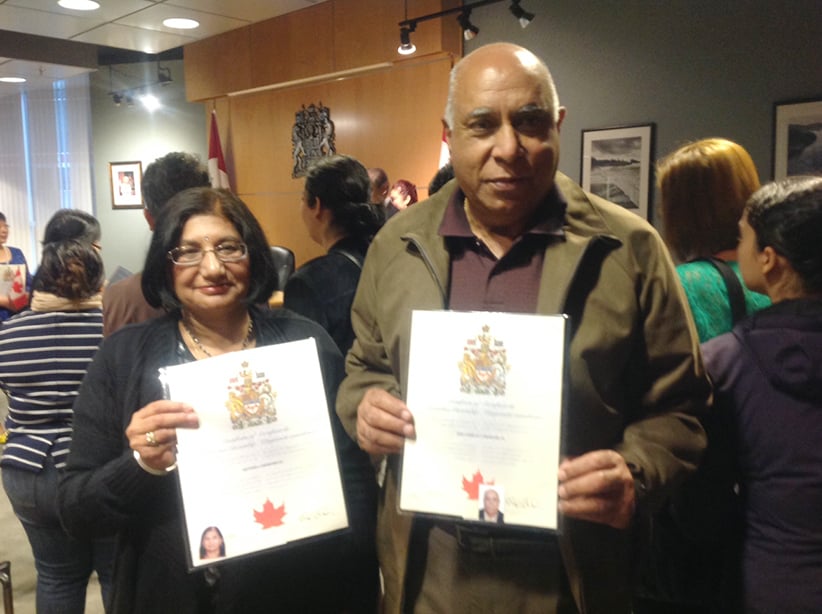

Oct 6 2015–Vancouver BC–Citizenship ceremony: New Canadians take the citizenship oath during a ceremony in Vancouver. (Photographs by Brian Howell)

Share

They arrived early, many before 8 a.m., in the warming promise of a Vancouver autumn day. They queued outside the federal office building in orderly fashion, as Canadians would, though they were not yet citizens. Not quite. A Canadian flag flapped listlessly overhead, on an outrigger flagpole attached to the building. One of the flag’s snap hooks had broken loose, leaving it hanging like a limp rag, as if an ill wind could rip the Maple Leaf from it moorings and send it fluttering to the sidewalk to join its deciduous brothers and sisters.

This, though, was not a crowd looking for gloomy portents. There was optimism in the air. On this Friday, Oct. 2, these people, born of 23 diverse nations, filed into this building to stand before a judge and recite the oath of citizenship. They walked in as South Africans, Iranians and Syrians; they walked out as Canadians. It is a moment native-born Canadians can never know. For them, it is not an accident of birth, this citizenship. They chose us, for any number of reasons, some carrying stories that would tear at your soul.

For those of us born on home soil, citizenship is a birthright. It’s something to be grateful for, if we are wise, but not really something that required much thought, definition or effort. We are born on third base, we Canadians, and we think we’ve hit a triple. Now, suddenly, in the last weeks of a federal election campaign, citizenship has become an issue that may determine who leads the country for the next four years.

Who gets to be Canadian? Is citizenship a right? Is it a privilege, as Immigration Minister Chris Alexander recently suggested? Can it be removed? If so, for what, and by whom? Can it be conferred on a Muslim woman whose face is veiled with a niqab or burka while she recites the oath of citizenship? What about those guilty of “barbaric cultural practices,” such as polygamy, forced marriage or female genital mutilation? What about your neighbours, who just had their newborn son circumcised? Is slicing off a squalling baby’s foreskin barbaric? Better phone the new Conservative-inspired RCMP tip line, just in case. Let the police decide.

Related: A Maclean’s primer on the niqab

Perhaps these are legitimate questions for discussion, but in the heat and thunder of the final weeks of an election campaign, it is more shouting than debate. Stripping the citizenship of a handful of convicted terrorists under the new Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act, or blocking the citizenship of women who want to veil their faces while reciting the citizenship oath, may have worked a marvellous tonic for Conservative fortunes, especially in Quebec. (And also, ironically, for their separatist rivals, the Bloc Québécois.) Whether Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau’s and NDP Leader Tom Mulair’s opposition to these Tory initiatives captures more of the so-called progressive vote is less certain. Citizenship is what moves the polls now. Syrian refugees? That was so last month.

It won’t feed your family, clean the environment or pare health care wait lists, still, there’s no denying the issue of who is worthy to be Canadian is as existential as it gets. If one is to understand citizenship, then, a good place to start is 877 Expo Blvd., Vancouver, one of dozens of citizenship courts across the country. Anyone is free to enter and watch, even jaded Canadians. It does the heart good.

Meet Ishver Girdharlal, 67, and his wife, Arvinda, 61, formerly of Johannesburg, now of Vancouver, and among the first in line this Friday morning. They are South African-born, though of Indian descent. Although the Girdharlals are South African citizens, they, as non-white children, were banned from certain parks and playgrounds. As adults, they were denied the vote until the end of apartheid in 1993. They endured, raised three children, now scattered to London, Los Angeles and Vancouver. They had a nice home, though, with Johannesburg’s notorious crime and murder rate, it was gated and guarded. They arrived home from a visit to Vancouver for the birth of their grandson to find they’d been robbed. Enough, Arvinda said. Time to move to a safe haven.

“I love Vancouver,” says Ishver, adding a caveat many in the city can understand: “It’s very expensive. I can’t even afford to buy a house here.” But they can vote, something they won’t take for granted. And yes, now as dual citizens, they have followed the election rhetoric on the revocation of citizenship for convicted terrorists who hold a second citizenship. Perhaps, they suggest, the debate is a bit of a luxury in such a peaceful country. It’s different when you have known fear, “when you have lived the reality,” as Ishver puts it. They can see the validity of the citizenship law that Prime Minister Stephen Harper champions, if the offences are narrowly defined as violent, treasonous acts. “I come from a country with lots of violence and, sometimes when I look at it, maybe he’s right,” Ishver says. Still, on such a fine fall morning, the politics of fear seem remote indeed. Says Ishver: “This will never be like South Africa was—and is.”

Later that Friday, the leaders of four political parties gathered in Montreal for the final debate of this long campaign. The debate was in French and the target audience were the volatile and ardently secular voters of Quebec. In a country with any number of crucial issues, the leaders spent an extraordinary amount of time debating the citizenship rights of a handful of convicted, if inept, terrorists, as well as the clothing of a 29-year-old Muslim woman named Zunera Ishaq, who came to Ontario from Pakistan in 2008. She wants to unveil her face to citizenship officials in private for identification purposes. She wants to wear her niqab when she recites the oath of citizenship with dozens of people. She is one of two women who have been denied citizenship for their refusal to publicly unveil since a prohibition against face covering while reciting the oath was introduced in 2011.

Polls show the law has huge public support, as Harper, and Bloc Québécois Leader Gilles Duceppe, his ally on matters textile, noted in Friday’s debate. They said the niqab is a symbol of oppression. Public disapproval of such veils also figured prominently in their interpretations of constitutional protection of religious freedom—though one searches in vain for a mention in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms that fundamental rights are grounded in poll data.

Related: This election will be won on citizenship issues. To our shame.

Civil libertarians took Ishaq’s case to the Federal Court of Canada. The judge ruled in her favour, as did the Federal Court of Appeal, which issued its ruling from the bench in mid-September. The Harper government immediately requested a stay of the ruling, pending an appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada. On Monday, the appeal court rejected the stay, meaning Ishaq is free to seek citizenship on her terms. Regardless, the issue is in play for the final stage of the election campaign, alongside the Conservatives’ attempts to use the powers of their toughened citizenship act to de-Canadianize and banish from the country members of the so-called Toronto 18, once they’ve served their sentences. One is Canadian-born, most are Pakistani-Canadians or from Jordan, Egypt or Iran.

There is no public sympathy for these al-Qaeda-inspired extremists. It leaves prominent immigration lawyer Lorne Waldman—who represents both Ishaq on the niqab case, and convicted terrorist Saad Gaya, born in Montreal to parents who are Canadian citizens—defending esoteric legal principles in an electoral climate of fear and anger. “I fully support the notion that if someone commits some of these heinous crimes, they should have the full force of the law thrown on them, but I don’t think our legal system recognizes that people should be punished twice,” he says of Gaya’s case. “Exiling [to Pakistan] someone who was born in Canada, and who has never been to the country they’re going to be deported to, is a horrible punishment.” Both the stripping of citizenship and the niqab issue were “manufactured by the Conservatives” to surface during the election campaign, Waldman says. “They’re playing to Islamophobia. When you put together the terrorism issue and the niqab issue, it really appeals to a base, crass fear that people have.”

Hours before Friday’s debate, the Tories doubled down by announcing their re-elected government would create an RCMP tip line Canadians could call if they suspect people are victims of such “barbaric cultural practices” as polygamy, female genital mutilation and forced marriage. “These practices have no place in Canadian society,” Status of Women Minister Kellie Leitch told a news conference. “By contrast, Justin Trudeau and Thomas Mulcair are more worried about political correctness than tackling these difficult issues that impact women.”

Critics were quick to point out the chilling historical precedents of past governments in other countries where the citizenry was encouraged to report the offending behaviour of fellow nationals. The Liberal and NDP leaders were left mounting a complex defence of rights with little public appeal.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

If such tactics are to be successful, they must feed a need. One of the most telling explanations of a changing national mood comes from an analysis by the polling company EKOS, entitled Tolerance Under Pressure? Among its conclusions: “Under the forces of growing economic and cultural insecurities linked to security and terror, we are seeing a sharp erosion of our openness to diversity and immigration . . . These issues, along with concerns about religious dress, have rarely been ballot-booth issues in Canada. They are, however, the key sorters underlying major shifts in the voter landscape.”

In other words, EKOS president Frank Graves told Maclean’s, things like the niqab “can be conditioning issues that frame your general sense of: ‘Where do I belong in the political spectrum? Who’s us versus others?’ ” It’s part of a recent growing “allergy to pluralism and multiculturalism,” says Graves. “I don’t think people will say: ‘I’m going to vote simply because of the niqab issue.’ But I do think it’s a factor.” The Conservatives, in contrast to their rivals, understand the role of values in engaging their base. “Emotions are what determine who wins elections.”

Last Friday morning in the Vancouver courtroom, 20-year-old Iranian-born Erfan Attar stood with 74 others, raised his right hand and recited in unison with his fellow new Canadians the oath, which begins: “I affirm that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada . . .” He has two priorities this Friday: Make it in time for his noon engineering classes at Simon Fraser University, and register to vote on Oct. 19. He arrived from Iran five years ago with this family. Canada, he says, is home now. He is carrying on a family tradition. His father is an engineer, though his credentials aren’t accepted here. “It’s the risk he took,” says Attar. “You’ve got to give up something to gain something.”

He has been following with disappointment the revocation-of-citizenship debate. “I think it’s wrong. I have a strong feeling it makes the citizens, the new immigrants, feel they’re not as important as older citizens,” he says. It makes his vote all the more important. “I live here now. It’s the future of this country. It affects me.” he says. “This has made me non-Conservative.”

There are no politics in this courtroom, of course. Here is an idealized, optimistic Canada, a foreign concept, if one tunes into the electoral debate. Prospective candidates arrived to find a little Canadian flag, a Maple Leaf pin and an Our Citizenship booklet on each chair. Photos of Canadiana played on a screen as people filed in: inukshuks, the royal family, soldiers squinting down rifle barrels.

Many governments have put their stamp on the rights and responsibilities of those entering the Canadian family. It was only in 1947, with the passage of the Canadian Citizenship Act under Mackenzie King’s Liberals, that Canadians ceased to be British subjects. It was Pierre Trudeau’s Liberals who introduced the concept of dual citizenship in 1977. “What does Canadian citizenship mean?” asked the Citizenship and Immigration website in 2004, under Jean Chrétien’s Liberal government. The general headings were: equality; respect for cultural differences; freedom; peace; law and order; followed by explanations of multiculturalism, bilingualism and environmental responsibility.

The Citizenship Act was extensively revised by the Conservatives in 2014, increasing residency times and strengthening language requirements for citizenship qualification, among other things. The revised study guide lists citizenship responsibilities as: obeying the law; taking responsibility for one’s self and one’s family; serving on a jury; voting in elections; helping others in the community; and protecting and enjoying our heritage and environment. “Defending Canada,” with careers in the Armed Forces, Coast Guard, or police and fire departments, is also much valued in the guide, as is the equality of women and men. “Canada’s openness and generosity do not extend to barbaric cultural practices that tolerate spousal abuse, ‘honour killings,’ female genital mutilation, forced marriage and other gender-based violence,” it warns.

The act also allows dual citizens to be stripped of their citizenship and removed from the country if convicted of such offences as terrorism, violation of human rights, war crimes and organized crime. During a campaign interview on a radio station in London, Ont., Harper left open the possibility that other heinous crimes might be added to the list. “Obviously, we can look at options into the future,” he said. “I think most Canadians, whether they are immigrants or other Canadians, understand that what demeans Canadian citizenship would be to allow war criminals and convicted terrorists and people who are actually out to destroy and defame our country to keep their citizenship.”

The toughened law has yet to be tested in court, and many legal scholars expect it would fail a constitutional challenge. “The law is, arguably, offside with [equality-rights guarantees] of the Charter,” says Evan Fox-Decent, a McGill University associate law professor. “The new form of citizenship is more akin to a benefit than a right—all the while maintaining the old form of citizenship as a full-throated right for those who have it.”

Much hinges on the perceived change that citizenship is now more privilege than right, says Donald Galloway, a University of Victoria law professor. “It’s not just a right; it’s the most basic of rights. It is the right to have rights, and, in that sense, all your other human rights are meaningless if you do not have it,” he says. “So, for our immigration minister to blithely state that citizenship is a privilege is not just a travesty, but a failure to recognize his own limited authority.”

“You will be given the most valuable gift: Canadian citizenship,” says the judge before administering the oath. “I know, for many of you, the journey has not been easy.” The judge tells the story of a five-year-old Vietnamese girl and her family who were “desperate to escape the turmoil and oppression of the aftermath of a long war.” They made many attempts by boat, only to be turned back and sent to re-education camps. “Try to imagine a five-year-old girl pushing a paddle boat in low-tide muddy water in the rain and dark, in water up to her neck. Unfortunately, she failed in the escape attempt, then ended up in still another re-education camp.” Finally, they escaped in a tiny boat, only to be caught in a violent storm on the South China Sea. They were rescued by a freighter and were sent to a refugee camp in Malaysia.

“When this little girl’s family finally arrived in Canada, she was nine years old, and it was her job to pick berries from five in the morning until 10 at night. When she grew up, she ultimately became a Canadian citizenship judge. I was that little girl.” The crowd gasped. Her name is Trang Nguyen, one of 69,000 “boat people” taken in by Canada after Saigon fell to North Vietnamese forces four decades ago. The government resettled 26,000, while the rest arrived, thanks to the sponsorship of church groups and individuals.

There are echoes of that today in the Syrian refugee crisis, faint echoes in harder times. Sitting in the courtroom, listening intently, was Ali Abo Nofal, his wife, Layla, and their daughters, Mariam, 14, and Rana, 10, a family that also knows what it’s like to be scared, displaced and trapped in refugee camps. Later, after meeting the judge, they pose for photos. Layla and Mariam, the older daughter, wear the hijab, a Muslim headscarf that covers only their hair and neck, and frames smiling faces on this day. With the family is Dave Talbot, part of a group from the United Church in Comox, B.C., which sponsored the family’s arrival in Canada four years ago.

Talbot’s mood vacillates between joy for the Abo Nofal family and anger at how the Conservatives are using the face-covering nijab as “a wedge issue.” He learned that morning of the attack in Montreal of a pregnant Muslim woman who was knocked to the ground as two teens tried to rip the niqab from her head. “My country,” he says, “it’s not the same anymore.” He brightens as he looks around the room at the hugs and happy chatter, at new citizens posing for photos. “With what’s happening in Canada,” he says, “this is what we need the most.”

Then Ali tells his family’s story: “I am a Palestinian from Iraq. I was born and spent all my life in Iraq. After [age] 45 years, when Saddam Hussein is gone, the Iraqi people said,‘We don’t like any Palestinians or any Arabic people in Iraq.’ And they killed my two brothers there. After that, we moved to the border between Iraq and Syria, to a camp. We stayed there for about 2½ years in a tent.” There were hot summers, cold winters and snakes. So many snakes. Then another two years in a refugee camp in northern Syria. “After that, we came to Canada.”

Ali is 51 years old. He was a pariah in Iraq, then a refugee. He had never been a citizen of any country until the morning of Oct. 2, 2015, the day he became a Canadian. He does not need a politician of any stripe to tell him the meaning and value of the certificate he clutches in his hand.

After the ceremony, there is also a chance to catch up with the Girdharlals, to shake their hands, to offer a welcome to the Canadian family. “Now,” says Ishver in reply, “we are one.” Yes, Ishver, as neat a definition of citizenship as you will find in our books of laws: all of us, good and bad, in this together. “We are one.” That’s how it’s supposed to work, isn’t it?