Is too much time in office bad for a politician?

Jim Prentice wants to enforce term limits on Alberta’s MLAs and premiers

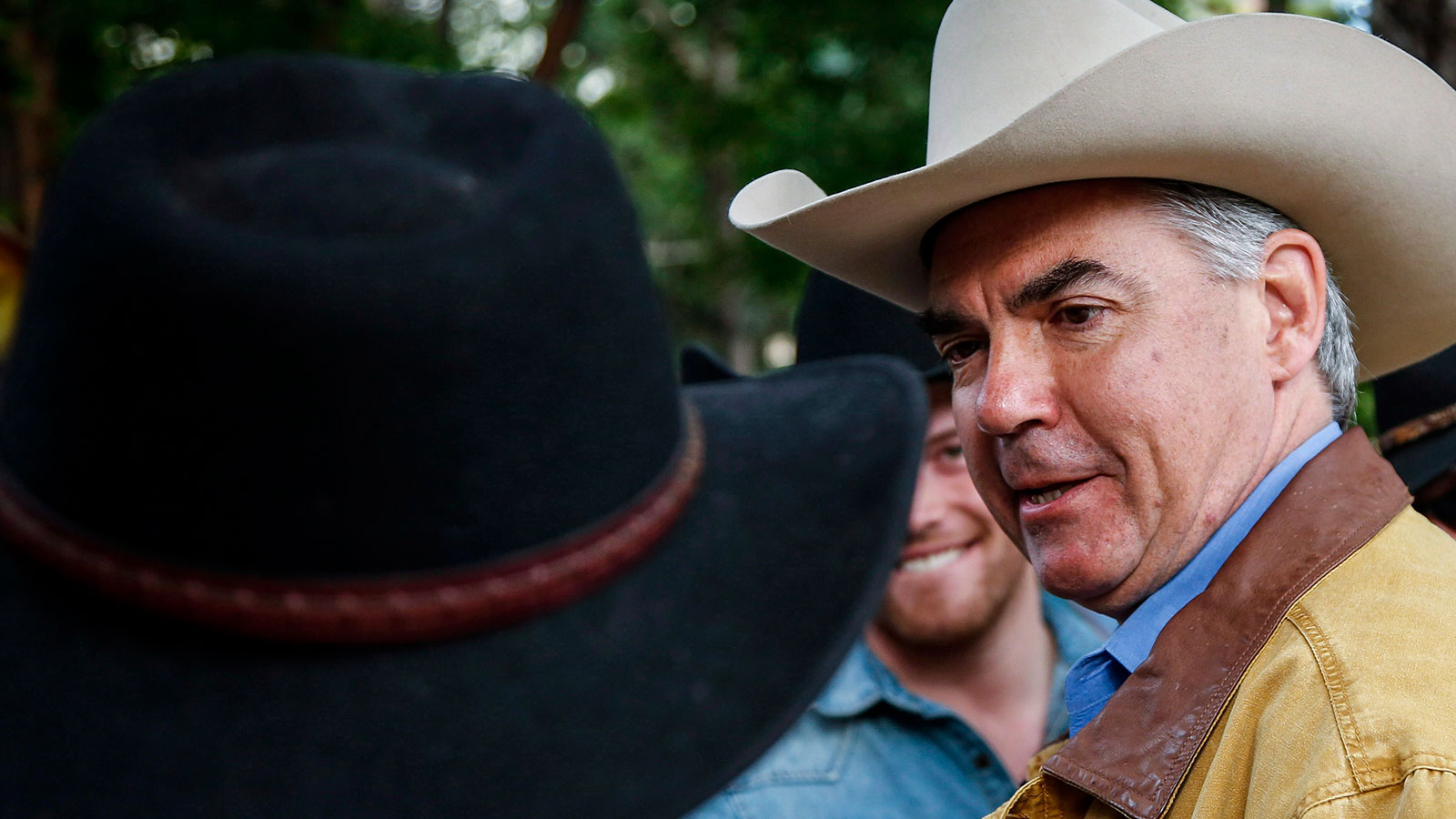

Jim Prentice, a former Conservative cabinet minister and now a banker, extolls the benefits of the $6.9-billion hydroelectric project at Muskrat Falls in Labrador as he addresses a business luncheon in Halifax on Wednesday, Sept. 28, 2011. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Andrew Vaughan

Share

Do some of our elected representatives spend too much time in office? Do they eventually lose touch with the wider world? Does this loss of touch occur somewhere around the 12-year mark?

Jim Prentice doesn’t like “career politicians” and so he would like to limit the amount of time an individual can serve as MLA or premier in Alberta: specifically by imposing term limits. This is possibly a bad idea, but it’s at least an interesting one to play with.

It’s important, at the outset, to define Prentice’s terms.

The term limit has a richer history in the United States (various nations also subject their presidents to such limits), where the time between elections is fixed and predictable. In the parliamentary system, while elections are bound to occur eventually, a vote can be called at just about any moment—governments can fall on votes of confidence and prime ministers and premiers can seek to have the legislature dissolved.

Sowhen Prentice invokes term limits—three terms for an MLA, two terms for a premier—he doesn’t really mean terms. As he explained to me in an interview on Tuesday, he’s really looking at years—12 years for an MLA, eight years for a premier. After being in office for that amount of time, an individual would, under Prentice’s plan, be ineligible to run in the next election. (Prentice isn’t the first to propose term limits in Canada. Belinda Stronach suggested term limits at the federal level three years ago—though she would have limited federal MPs to two consecutive terms.)

There is at least one caveat.

If I understand correctly, an individual’s years as premier do not count against his or her years as an MLA. So you could, presumably, be an MLA for eight years and then premier for another eight years.

Now, this might not be constitutional. (Prentice says he’s open to pursuing the limits through provincial legislation or the internal rules of the Progressive Conservative party in Alberta.) But even if it is allowable under the Charter, is this the sort of thing we should want to see imposed on our political system? Would term limits improve matters? Would this address any of what ails our politics? Is there some great principle that the term limit makes real?

“Take it firstly as a bit of an operative philosophy about the need for renewal and new people and new ideas and new energy—both in the Progressive Conservative party, but also in government generally,” Prentice says.

For that matter, Prentice says he has always approached his own political career with this understanding. “I’ve always felt very strongly about this,” he says. “The very first speech I gave when I ran federally was that I was stepping forward as a politician, not as a career politician, but as a citizen, who believed that it was important to make a contribution in the federal political stage and that I would stay there no longer than 10 years. People were surprised when I left, but I left because it was like nine-and-a-half years. And I said, go back to the very first speech I gave. I just don’t believe in career politicians.”

Woe is the career politician, he or she whose ability to repeatedly win the support of his or her constituents is to their eternal shame.

Don Braid, Dave Cournoyer, Dale Smith and now Independent MP and former Alberta MLA Brent Rathgeber have had their kicks at Prentice’s proposal and their analyses are worth reading. I’ll try not to repeat their concerns, but I don’t like the idea of term limits either. In fact, I dare say there is much to commend the career politician. At its worst, the term limit strikes me as a kind of anti-politics gesture—a concession that politicians and the other parts of the system cannot be trusted to best manage our public affairs without this restriction. At the least, I think it is a crude and problematic mechanism for engineering change.

But, if nothing else, Alberta (or the Alberta PC Party) might be about to embark on a fascinating experiment in parliamentary democracy. At the very least Jim Prentice has given us something against which we can test our sense of the political system.

From where I sit, that some MPs are still here after 12 years seems like the least of our problems. Perhaps the situation is somehow different in Alberta.

Wikipedia tallies 36 states that impose term limits on governors and 15 states that impose term limits on legislators, but of course it’s difficult to make straight comparisons between the congressional and parliamentary systems. In our case, the prime minister or premier is drawn from the legislature and derives his or her cabinet from that same group. Imposing term limits on that parliamentary system creates unique complications. It would, for instance, limit a prime minister’s cabinet options. (Going back to Stephen Harper’s first cabinet, he wouldn’t have had former Reform MPs Jason Kenney, Chuck Strahl or Monte Solberg.) A second-term prime minister who had served eight years as an MP beforehand would become the most experienced member of the legislature.

The details will need to be worked out and the ramifications considered. Would one’s clock start again if they were defeated or otherwise stepped away before reaching the 12-year mark? Could a deposed eight-year premier go back to being an MLA? How would this impact opposition parties and how they select leaders (budgeting a prospective leader’s remaining allowable time in the legislature would seem to be necessary)? Would opposition parties have to be careful not to select anyone who would reach the 12-year mark before the next election or could a 12-year MLA run in an election if he or she had some chance of becoming premier? How would the so-called “lame duck” status of second-term prime ministers impact the work of the government and the legislature?

Imagine a prime minister at the six or seven-year mark, but with a minority government. How would the looming eight-year mark impact the opposition’s willingness to defeat the government or the government’s willingness to trigger an election? (Keeping in mind that an unscrupulous or popular prime minister could extend his tenure by a few years if he won a new mandate shortly before reaching the eight-year mark.)

If term limits were suddenly imposed tomorrow at the federal level, Stephen Harper would be ineligible to lead the Conservatives in the 2015 election, but so would possible successors like Jason Kenney and James Moore. In all, 50 of 307 current MPs would be ineligible for the 2015 election. You can judge the quality of those MPs for yourself—go here and scroll down. (Some of those MPs aren’t running in 2015 of their own volition.) About the same share of current Alberta MLAs would similarly be ineligible.

(Some enterprising researcher might figure out what percentage of MPs and MLAs ever end up going beyond the 12-year mark. You have to scroll a fair way down this tally of our 4,214 federal MPs before you reach those above the 13-year mark.)

The majority of MPs and MLAs might not be impacted by such a change and the prospective office holders would no doubt adjust to the new rules, but some subset of potential office holders would be eliminated.

Beyond the practical issues, the concept of term limits comes down to very fundamental questions about how we imagine our elected representatives should be.

Prentice says his idea is about renewal and opening politics up to new voices and new ideas. But he also has a certain understanding of how elected public office should be viewed.

We don’t, of course, impose term limits on doctors, lawyers, teachers, judges, civil servants or police officers—public jobs that are integral to the functioning of civil society. So why would the job of elected representative be any different?

“I believe in the duty of citizens to step forward for public service,” he says. “I don’t believe that politics should ever become a job.”

As he has said elsewhere: holding elected office should be viewed as a public service, not as a career.

There’s a certain element of practicality to this. An MP might wish to make a career of it, but the voters might feel differently. You might be able to draw loose parallels to any chosen career, but it is likely harder to maintain work as a career politician than it is to maintain work as a career teacher.

There is also a certain appeal to the idea of the teacher or lawyer or businessman or factory worker stepping forward for public office and thus being brought together with other noble citizens for the purposes of representing us and, together, managing the affairs of the country.

But is that ideal particularly useful?

Term limits idealize the new, but I suspect that ideal underestimates both the learning curve for the newly elected and the value of experience. We can overestimate those things too, but let’s give some due to the knowledge and skills that can be gained from representing constituents, working in parliament, studying public policy and seeking re-election. Probably the 12-year MP is going to possess some things that a new MP lacks—things that would benefit a legislature.

Maybe we don’t want a legislature composed entirely of career politicians, but the career politician is not an inherently ruined character. Jack Layton and Jim Flaherty were career politicians. John A. Macdonald and Wilfrid Laurier were career politicians. Peter Lougheed and Bill Davis were career politicians.

At the risk of descending into semantics, we might accept that public office is a job or at least that there is nothing inherently wrong with deciding you want to do it for 20 or 30 or 40 years and equally managing to win the necessary public consent to do so.

In the abstract, that the public would repeatedly renew someone’s term in office seems an odd thing to object to—indeed, that we would effectively limit the democratic will of the public is probably the strongest argument against term limits. Do we imagine that some voters do so against their will?

Surely there might be ensconced incumbents who we might be somehow better off without. But for the sake of getting rid of such individuals, how many valuable and valued contributors would be barred?

Perhaps that’s a necessary sacrifice if you view elected office as a corrupting influence. And that, I think, is at least one of the implicit messages of a term limit.

Prentice quibbles with me slightly on this point, but only slightly: “I don’t suggest that it’s corrupting. I do suggest that you lose your grounding. And you cease to be a citizen legislator and become a person who has a job.”

As he said to me at another point, “I think if people stay too long they get out of touch.”

That strikes me as a rather sad conclusion. If it is the case that our elected representatives become deluded by significant time in office, we might ask why that is. To presume that losing touch is an inevitable result of elected office would seem to be rather defeatist.

Of course, the job itself, by its definition and the means for retention, is about not losing touch. At least with a segment of the popular numerous enough to get you re-elected.

But then the idea of the term limit would seem to be predicated on the notion that regular elections aren’t sufficient. That, given enough time, some significant number of elected representatives will lose their way. That without strict limits on the service of office holders, the political system—the politicians, the parties, the media and the voters—is not capable of being sufficiently vibrant or healthy.

Or, if you prefer a nicer spin, that a system with term limits would be so superior that we should force a major restriction on democratic expression.

You might, of course, try other things first—empowering backbenchers and the legislature, opening up the policy process and candidate selection, making it more viable for independent candidates to seek office and so on. A government interested in new voices and new ideas could simply invite those into the public debate and generally entertain them.

“In terms of reactions to this idea, there’s quite a difference between what the general public feels and what people who are part of the system feel and I’ve been quite struck by that,” Prentice says. “The public is overwhelmingly supportive of what I’ve been saying. The people who are opposed to are people who are part of the system. It’s very interesting.”

I suppose that split doesn’t entirely surprise me. I dare say one might suggest that while members of the general public are well-positioned to comment on their satisfaction with things, they are not always in the best position to know what precisely should be done to change things.

Here, as with the rest of it, there’s a question about whether those who are experienced within the system possess valuable insight that should not be too cavalierly dismissed.