Trudeau’s LGBTQ apology is a good start, but it’s not enough

Opinion: Commitment to long term and sustainable support for LGBTQ community-based social services will make the apology worthwhile

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau waves a flag as he takes part in the annual Pride Parade in Toronto on Sunday, July 3, 2016. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Mark Blinch

Share

John Paul Catungal is an instructor of critical race and ethnic studies at the Social Justice Institute and a faculty associate of geography and Asian Canadian and Asian migration studies at the University of British Columbia. This piece first appeared at The Conversation.

On Tuesday, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau plans to make a formal apology on behalf of all Canadians to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people who have been imprisoned, fired from their jobs or otherwise persecuted in the past because of their sexuality. Some of those who lost their jobs as part of the so-called “gay purge” are seeking financial redress through an active class-action lawsuit against the Canadian government.

Tuesday’s apology will be an important, albeit long overdue, step forward to say sorry for the history of state-sanctioned discrimination against LGBTQ people in Canada. Before we start celebrating, however, we need to take a step back and consider the scope and implications of this apology.

Addressing historic wrongs is important. An apology, as an acknowledgement of structural violence, can offer a starting point for moving toward a more socially just, perhaps even queerer, future.

When governments take responsibility for the harms they caused, it communicates to those most intimately affected that their experiences are valid. The trajectory of their lives are shaped not by their individual failures but by a broader set of constraining contexts.

An apology can also support community-based strategies toward both individual and collective healing. It can open up opportunities for further action. For example, LGBTQ organizations will rightfully make strategic use of Trudeau’s formal apology. They will likely make further claims on the government for further legislative and policy changes and for more sustained support for services and programs for LGBTQ communities.

But an apology can only have a positive impact if done properly. An apology, in and of itself, is absolutely not enough. The apology must be more than a mere symbolic gesture with little real impact.

Action is needed. Commitment to long term and sustainable support—financial and political—for LGBTQ community-based social services is necessary. Especially since many of the structural issues that require the need for these services are themselves legacies of government-sanctioned homophobic, transphobic and heteronormative violence.

Connecting inequalities

We also need to recognize the massive inequality within LGBTQ communities. Scholars and activists have documented that, among members of LGBTQ communities, trans people, especially trans women and trans people of colour, continue to experience disproportionate violence on the streets, in schools and in the workplace.

Stronger policy and legislative actions are needed to combat violence against trans people. This means actively supporting community-based strategies with trans people in leadership roles.

While the focus on LGBTQ communities is a good start, it is not enough. We need to look more broadly at the diverse intersectional effects of heteronormativity as a government-sanctioned project.

After all, biased government policies and practices were key to the enactment of violence against many communities that overlap with LGBTQ ones. For example, while the LGBTQ community was disproportionately impacted by homophobic government responses to HIV/AIDS in the 1980s, other affected communities were also touched intimately by the effects of discriminatory AIDS-phobic, homophobic, racist and ableist discourses and attitudes.

Moreover, Indigenous scholars like Martin Cannon and Bonita Lawrence have powerfully documented how Canadian government strategies to “civilize” Indigenous people—through the Indian Act and residential schools—relied upon Euro-Christian norms of binary gender and heterosexuality imposed upon Indigenous communities. Colonial strategies of imposition sought to displace the complex cultural systems of gender and sexuality of many Indigenous communities.

The persistence of binary notions of gender continues to be felt not only by Indigenous people, but also by trans people as they fill out government forms like passport applications that insist that male and female are the only possible choices for gender.

We need only look to Two-Spirit organizing today to see not only the ongoing effects of colonial heteronormativity, but also, perhaps more importantly, the perseverance of Two-Spirit people in the face of the continuing gender and sexual violence of settler colonialism.

In addition, government policies that have restricted the idea of “family” to the heteronormative nuclear family ideal affected not only LGBTQ people, but also forms of family that do not conform to such a definition.

It’s worth asking, for example, whether single mothers, divorced families and other non-nuclear configurations of family were also adversely affected by the same heteronormative state prescriptions that targeted LGBTQ people.

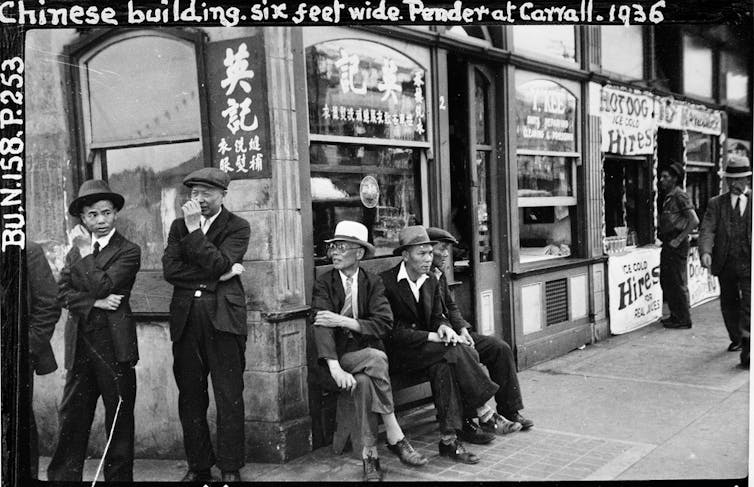

Race also needs to be part of our public conversation about the formal constitution of the idealized nuclear family. Consider, as one example, that the historical Chinese head tax legislation was a way for the Canadian government to restrict Chinese migrants’ capacity to form families. This government policy worked both to curtail the reproduction of racialized communities and to secure a vision of Canada’s future as a white settler nation.

Federal policies concerning migrant family separation and reunification remain contentious today, particularly for racialized labour migrants such as agricultural workers or nannies whose presence in Canada is conditional on leaving their families behind.

‘Homonationalism’

Another concern is the likely possibility of Trudeau’s apology being mobilized to measure how much better Canada is than other parts of the world. Such “homonationalism,” to borrow from the scholar Jasbir Puar, can have the racist effect of ranking cultures and countries using LGBTQ-friendliness as a metric of progress and civilization.

This can serve to downplay the continued gravity of certain LGBTQ2 struggles here, especially those experienced by trans folks of colour, while also facilitating punitive actions and racist attitudes towards cultures deemed “backward” by such metrics.

It is important to think critically about state-sanctioned homophobia in such places as India and Uganda. But rather than employing a racist-colonial discourse of these countries’ irredeemably homophobic cultures, it is imperative that we think through how histories of colonialism and the continuing presence of transnational religious missions shape the political landscapes of gender and sexuality in these places today.

Through shared histories of British colonialism and the settler colonial imposition of heterosexuality, Canada is heavily entangled with these places. Canada is a possible node in transnational networks of fundamentalist religious missions that fuel homophobia, including state-sanctioned forms, in these places. A too-celebratory account of the apology as a patriotic nod to Canadian exceptionalism can serve to silence these other ongoing issues.

In short, the scope of apology is worth interrogating: Exactly what—which wrongs, actions, laws, policies and silences—is the government apologizing for? How does such a limited definition of scope limit our understanding of the scope of state heteronormativity itself?

Broadening our approach allows us to see that Canada has had a longstanding and broad interest in governing sexuality, the effects of which have been felt not only by LGBTQ2 people, but also by many others.