Was the road to a Donald Trump impeachment paved by Andrew Johnson?

The 17th U.S. president was a cracker-barrel orator who defied the partisan labels of his time—and stepped right into a trap set by his congressional foes

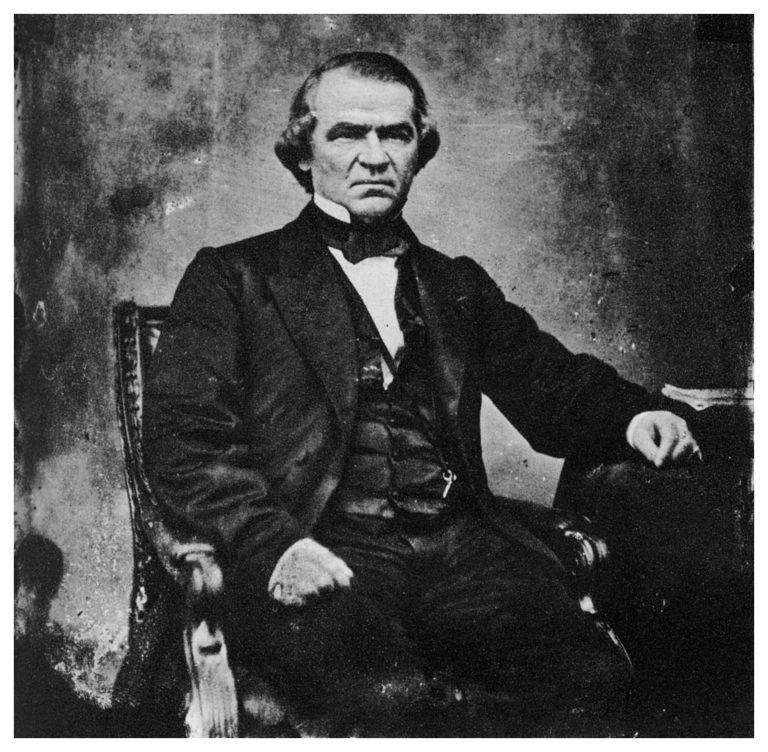

Andrew Johnson’s policies of conciliation towards the South after the Civil War and his vetoing of civil rights bills led to bitter confrontation with the Radical Republicans in Congress (Photo: Print Collector/Getty Images)

Share

The dark and muddy backstreet that is known as Impeachment Alley wends its way from Hope, Arkansas toward its eventual terminus in the Borough of Queens, New York. Along the way, it passes through a handsome Tennessee city that still proudly honours one of the most dishonoured men ever to live in the White House.

You see his name and image everywhere you go in Greeneville, Tennessee—at the Andrew Johnson Bank, on Andrew Johnson Boulevard, and in the life-sized bronze of Andrew Johnson at the corner of College and Depot Streets. You learn of his career in the artifacts and the videos at the Andrew Johnson National Historic Site, at Andrew Johnson’s homestead, at Andrew Johnson’s humble tailor shop—lovingly preserved exactly as it was in the 1830s—and at the hilltop gravesite where the 17th president of the United States has been sleeping since 1875 with a copy of the Constitution under his rotting head.

“When you think about it,” notes a librarian on Main Street, “he served at one of the worst times in our history. I don’t think that he’s seen as a villain now.”

History is a patient goddess. In the 22nd century, rocket-loads of tourists may orbit to Jamaica Estates to stand beneath the life-sized bronze of Donald Trump and to tour his family’s mansion on Donald Trump Boulevard, just as they flock to Bill Clinton’s step-father’s house in much-less-wealthy little Hope. While the anti-Trumpers rage in Washington, it is instructive to tour the exterior states and learn about the scoundrels and the saints who came before him.

Impeached in the House of Representatives in 1868, then rescued from removal from office by a single senator’s vote that reputedly was gained by bribery, Andrew Johnson and his ordeal of attempted partisan regicide echo loudly down to 2019, when a House-load of Democrats in the mood for a lynching may well do the same to The Donald.

“Off the record, I am strongly rooting for Trump to be impeached,” that librarian confides. “But the clientele we deal with here are staunch Trump supporters, and we have to be kind to them.”

“Your Andrew Johnson is not ranked very highly,” a visitor observes.

“And he never will be,” the librarian shrugs. “But he did a lot of good in Greeneville, donating land for schools, and as mayor and a state legislator.”

An aggregation of scholarly polls taken over the past half-century inhumes Andrew Johnson two or three shovelfuls from the very bottom of the pit of unable presidents, barely on top of the accursed James Buchanan, who took no action as the Southern states seceded on the precipice of civil war, and, in the most recent assessments, just above the unspeakable (to liberal academia, at least) Trump himself.

Johnson is even reckoned the inferior of William Henry Harrison, who died after having only 30 days in office in which to screw things up.

Still, says a ranger at the Andrew Johnson Visitor Centre in downtown Greeneville, “they love him here.”

RELATED: What Trump’s impeachment might look like—and how dangerous it could be

Andrew Johnson was a professional fabric-stitcher who never sat through a day of formal schooling, a teenaged runaway from an apprenticeship in North Carolina who found refuge on what then was the Western frontier, a cracker-barrel orator who rose from village politics to the very nucleus of power, and a Southern slaveholder who held fast to the Union even as the nation split apart. He became president the night that Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, but he never outlived the false and heinous rumour that he was the secret mastermind of the conspiracy that killed the beloved Honest Abe.

“Before the rebellion,” Johnson wrote during the Civil War, “I was for sustaining the Government with slavery; now I am for sustaining the Government without slavery. In my opinion, freedom will not make negroes any worse, and will result in their advancement. I am for an aristocracy of labor, of intelligent, stimulating, virtuous labor; of talent, of intellect, of merit; for the elevation of each and every man, white and black, according to his talent and industry.” He had set his personal chattels free the year before.

In mid-September, it is a quiet—in fact, a very quiet—afternoon at the Andrew Johnson Visitor Center; there’s not another tourist in sight. The next morning, a couple from Illinois arrives—they are inveterate presidentialists who enjoy visiting every location from the birthplace of Silent Cal Coolidge to Millard Fillmore’s tomb.

“I have wrestled with poverty, the gaunt and haggard monster,” we hear Andrew Johnson say in one exhibit, in words that Donald Trump probably never has uttered. “I have met it in the day and night; I have felt its withering approach and its blighting influence . . .”

In 1864, Abraham Lincoln, a Republican, chose Johnson, a Democrat, to be his running mate in Lincoln’s quest for a second term. When Lincoln was killed, Johnson, whose assigned assassin got drunk that night and shrank from committing murder, took the reins of state. People whispered that the Tennessean had set the whole thing up.

RELATED: How does impeachment work, and could it happen to Donald Trump?

The Senate majority at the time was in the grips of men who proudly called themselves Radical Republicans. President Johnson proposed to re-absorb the beaten Confederacy by allowing each state to decide which rights would be granted to millions of former slaves. The Radicals favoured full suffrage for African-American men, who then would be expected to show their gratitude by supporting Republican candidates. Eager to dispose of Johnson, they set a trap.

Congress passed a law that forbade a president from firing any government official who had been confirmed by the Senate and pointedly made it a “high misdemeanor” to do so. Defiantly, Johnson dismissed the Secretary of War. The trap sprung, and the case came to the Senate for trial.

Replace the words “Secretary of War” with the words “FBI Director James Comey,” and you can see where we are going with this.

The radicals needed 36 votes to get rid of Andrew Johnson. A Kansas Republican named Edmund Ross voted no and they got only 35. It was whispered that Ross had been paid a Trumpian sum to save Johnson’s job.

“There have been all sorts of theories, from monetary to Masonic, to explain why each senator voted as he did,” says cultural resource manager Kendra Hinkle of the Andrew Johnson National Historic Site. “There may be some truth in all of them. However, I will use Ross’s own words to explain the decision he made.

“In a letter to his wife a week later, he wrote: ‘Millions of men are cursing me today but they will bless me tomorrow. But few knew of the precipice upon which we all stood.’”

A century-plus after this, Bill Clinton, impeached for lying about his sexual activities with a White House intern, was acquitted by a count of 55-45. In 1974, Richard Nixon, certain to be convicted by Congress, resigned before he could be voted out. No American president has been removed from office—at least not yet. In Brazil and South Korea and Guatemala and Paraguay and Lithuania and Indonesia, yes, but not in the U.S.A.

RELATED: Cohen pleads guilty; Manafort convicted. And Trump goes on.

We don’t know yet if Democrats will win enough seats in the House of Representatives in November to impeach Donald Trump and send the case to the Senate for trial. We don’t know yet whether Robert Mueller will deliver a litany of malfeasance, collusion, and corruption so damning that no man or woman of either party will vote to exonerate the 45th chief executive. We don’t know yet if Donald Trump will quit in the face of certain expulsion. We only know that the United States has been to this cliff before.

“I have performed my duty to my God, my country, and my family,” Andrew Johnson wrote not long before a stroke ended his productive and tempestuous life in 1875. “I have nothing to fear—death to me is the mere shadow of God’s protective wing; beneath it I almost feel sacred … Here I will rest in quiet and peace beyond the reach of Calumny’s poisoned shaft—the influence of envy and jealous enemies—where Treason and Traitors can have no place. Adieu.”

A century and a half later, in a country whose two halves revile each other almost as much as they did in the 1860s, the rise and fall and partial resurrection of Andrew Johnson holds a trenchant lesson.

“Andrew Johnson was a president of the United States, a title held by only 45 men in our nation’s history,” says Kendra Hinkle. “Whether these men are considered successes or failures by the standards of the day, each has contributed to the totality of where we are as a nation in 2018. Many of the questions the people of Andrew Johnson’s time grappled with are still relevant topics we struggle with today.”

“I believe that my father was the greatest man that this country ever produced,” a daughter named Martha Johnson Patterson once said, long after the 17th president was placed in his sepulchre, high above Impeachment Alley.

“No one has more faith in the American people than my father. He will be your greatest, your truest and your most loyal champion,” once declared Ivanka Trump.