A Republican race for the political middle

Can Bush, Romney and Christie save the Republicans from another race filled with fringe candidates?

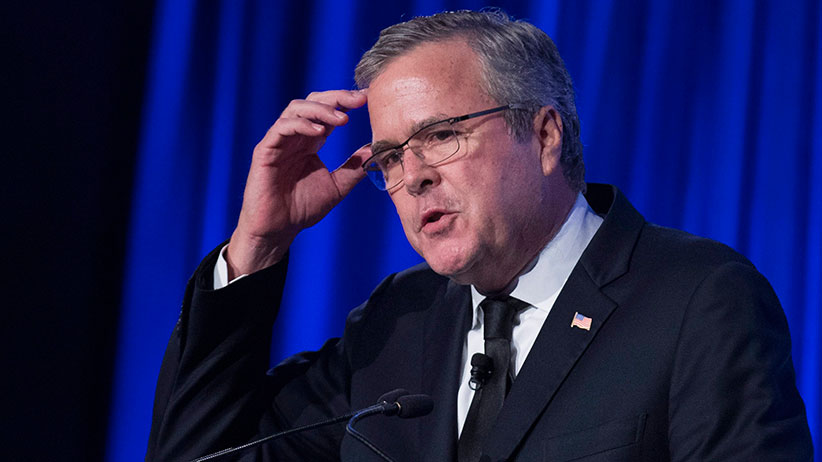

Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney and former Florida Governor Jeb Bush (L) pose for a photograph together after a 2012 Romney for President campaign rally in Tampa, Florida October 31, 2012. Brian Snyder/Reuters

Share

The Republican presidential contest is getting started and it already feels different. Hillary Clinton is eclipsing the Democratic field, but the Republican contest is wide open, with the potential to be what their 2012 contest was not: a race for the political middle.

The 2012 Republican debate stage was crowded and occasionally messy. Texas Gov. Rick Perry forgot the name of a government agency he planned to eliminate. Congresswoman Michele Bachmann claimed vaccines cause “mental retardation.” And, before withdrawing amidst allegations of sexual harassment, businessman Herman Cain boasted that he did not know the name of the president of “Uzbeki-beki-beki-stan-stan.” That field was the “weakest in memory,” strategist Karl Rove recently wrote in the Wall Street Journal.

It was also highly ideological. Competing in the wake of the Tea Party wave, candidates in 2012 tried to outdo one another with displays of conservative fervour. Eventual nominee Mitt Romney, the one-time moderate governor of the liberal state of Massachusetts, resorted to describing himself as “severely conservative” and advocated for making the lives of undocumented immigrants so unpleasant that they would “self-deport.”

“In 2012 we saw a half-dozen candidates all competing on the right—for social conservatives and the Tea Party,” says Timothy Hagle, a political scientist at the University of Iowa. “This time around, we have more people competing for that more middle- or centre-right type candidate.” Three big names now dominate conversations: Jeb Bush, Mitt Romney (again) and Chris Christie. This could be the strongest and “the most volatile, unpredictable Republican contest most Americans have ever seen,” predicted Rove.

Today, the closest thing to a Republican 2016 frontrunner is Bush, the brother and son of two former presidents, and a former governor of the key swing state of Florida. Bush is a policy wonk with moderate positions on immigration and education reform that irritate many in his own party, but that appeal to the party’s leaders and big-dollar donors. Though he has not yet announced his candidacy, already his allies have told financiers that they aim to raise a daunting $100 million for his campaign—a move aimed in part at intimidating potential rivals into staying out. But Bush faces more obstacles than those enjoyed by George W., the self-professed “compassionate conservative” candidate, in 1999: he has not held office since 2007, the family name now carries the baggage of his brother’s misadventures in Iraq, dynasty fatigue, and the fact the party’s grassroots has moved to the right.

“His brother was clearly the choice of the Republican political elite and could sit back and let people come to him in Austin,” says David Karol, a political scientist at the University of Maryland and co-author of The Party Decides: Presidential Nominations Before and After Reform. “It doesn’t look like Jeb is going to have as easy a path to the nomination as his brother did.”

Moreover, the middle is getting crowded. Romney injected urgency into the race by telling a private meeting of donors on Jan. 9 that he was considering running again. He has since contacted supporters and gave a speech denouncing Obama’s policies to a Republican meeting in San Diego.

Bush and Romney are two high-profile business-friendly figures for many of the same donors and top campaign staff and strategists. “If this becomes Jeb vs. Romney, it’s going to be an ugly race,” Dan Senor, a former Bush adviser, told Bloomberg recently. “It’ll probably get pretty personal pretty quickly. It’s not going to be ideology that divides them.”

Romney argues he’s been vindicated on a number of policy disputes with President Barack Obama, but the former financier—and owner of a mansion with a car elevator who spoke dismissively of “47 per cent of Americans,” whom he claimed supported Obama because they pay no income tax and feel entitled to government support—faces deep skepticism. Romney has to explain “why he would be a better candidate than he was in 2012,” the conservative Wall Street Journal editorial page declared recently. “The answer is not obvious.”

Also squeezing into the moderate-Republican-governor camp is Christie, New Jersey’s governor, who has experience working with a Democratic legislature in a northeastern state, and even angered his party in 2012 by embracing Obama amidst the destruction of hurricane Sandy. This month he appointed a finance chairman, launched a campaign funding organization, and held a private meeting for reporters from the national media and did not invite his local press corps. “I believe in a New Jersey renewal, which can help lead to an American renewal,” he said in his state policy speech this month. (He is betting that national voters will overlook the “bridgegate” scandal in which his staffers created traffic problems for a suburban community after its mayor failed to endorse Christie in an election. Christie said he was not aware of their actions.)

State leaders like Bush, Romney and Christie have an advantage over rivals in Congress: they can more easily develop policy accomplishments while maintaining distance from some of the partisan and ideological battles on Capitol Hill that have turned off voters. “They can run against ‘the dysfunction of Washington’—against Obama and implicitly against congressional Republicans,” says Karol.

The three high-profile figures with the potential of broadening the party’s appeal are also a welcome sight to party leaders. The Republican elite emerged from the last election concerned that the divisive primaries and the parade of fringe candidates damaged Romney, painting the party into an ever-more narrow caricature. After the last election, the party put together a report on broadening its appeal beyond its hard-core supporters. It decided to reduce the number of primary candidates’ debates and start them three months later—in August instead of May.

However, there are other potential candidates who are likely to make ideological principles a centre of their campaigns. The governor of Wisconsin, Scott Walker, is a conservative hero for his aggressive battles against labour unions in his home state. And the colourful characters are back, too. Texan Rick Perry is likely to run again. Other long-shot candidates include brain surgeon Ben Carson, who wears his political inexperience as a badge of honour, but has struggled with an episode of plagiarism and a tendency to make pronouncements such as declaring Obama’s health care reform “the worst thing that has happened in this nation since slavery.” There is also former Hewlett-Packard executive Carly Fiorina, who failed in her 2010 Senate bid in California. Social conservatives Rick Santorum and Mike Huckabee are also expected to mount campaigns.

Many of the candidates will gather Saturday to test-drive their messages before the Iowa Freedom Summit, a conservative conclave in the rural state that is the first to make a pick for the party’s nominee, a full 12 months away.

Other factors may dash hopes of those who seek a centre-right primary. Despite the public backlash that Republican hard-liners faced after they shut down the government in 2013 in a failed effort to derail Obamacare, the right wing of the party remains powerful. Conservatives have been emboldened by Republican success in last November’s congressional elections and see their Senate victories a repudiation of naysayers urging the party to moderate its approach.

Moreover, the people who vote in party primaries tend to be more ideological than general election voters. The last candidate who tried to paint himself as a different kind of Republican was former Utah governor Jon Huntsman; he fretted about climate change and took a job as Obama’s ambassador to China. In the 2012 primary, he got 0.6 per cent support in Iowa’s contest, although he finished third in New Hampshire, where non-Republicans were allowed to vote. “The media loved him but he got no traction at all. That was the cautionary tale,” says Karol.

Meanwhile, the Tea Party forces are also gearing up. Ted Cruz, the Texas senator who led the government shutdown, is also considering running. “Do we go back to the same old, same old? Or do we stand for principle?” Cruz asked the South Carolina Tea Party conference in a speech last week. He emphasized that a moderate candidate will not excite the party faithful to organize and vote. “If we nominate another candidate in the mould of a Bob Dole, John McCain or Mitt Romney . . . the same people who stayed home in ’08 and ’12 will stay home in ’16 and the Democrats will win again,” Cruz said.

Republicans now have a year to decide if they agree.