American politics? They’ve become a family affair.

It goes well beyond the Clintons and the Bushes: political families have become a staple of U.S. politics, at every level.

(Photo illustration by Lauren Cattermole and Richard Redditt)

Share

Three wooden steps above the patch of pavement where one of the most beloved and reviled politicians in American history crumpled and died, a father’s son awaits his own election day. Known to the world since childhood as Christopher or Chris, the tyro, age 34, is standing for the city council of Washington as the one true heir of the dad whose name he now goes by: Marion Barry.

“When I was handing out flyers the other day, I got a flashback that it was 1992,” the son is saying, standing on what had been his father’s front porch, looking down at the spot where heart failure felled Washington’s “mayor for life” last November at the age of 78. “He was on this same street, doing the same thing. He had just come home from jail. That was the first summer my mother let me go live with him. That was our real bonding time.”

The elder Marion S. Barry served as mayor for four terms, interspersed with a six-month sentence for an infamous session of crack cocaine smoking with an ex-girlfriend who was working for the FBI (“Bitch set me up!”). Following his tumultuous mayoralty, Barry repeatedly was elected as a humble councillor from Ward 8, the capital’s most benighted, neglected and destitute neighbourhood.

Now the (only) scion of his clan is campaigning to take his seat. In a season of Clintons and Bushes (and Trudeaus, of course), the Barry name isn’t the only one whose political currency is being assayed. Congress and the 50 state houses are replete with the widows, nephews, daughters, siblings, sons and cousins of departed politicians. But Chris Barry may be the only one who has purposely altered his public name; in his case, in order to capitalize on this capital’s late, reprobate hero.

“If you meet 10 voters in Ward 8, how many say ‘I loved your father?’ ” candidate Barry—listed on the ballot as “Marion C.”—is asked. “Ten out of 10,” he replies. “And how many of them say, ‘Your father got me my first job?’ ”

“Eleven out of 10!” a supporter leaning on the balustrade interjects.

“If I wasn’t ‘Barry?’ ” Barry the younger muses. “I say the name helps, but even without the name, I’d still feel the same, have the same passion.”

The son contends that he alone can carry on his father’s legacy. For the past few years, however, he may have been overemulating his old man, making numerous court appearances for drug offences. He currently is facing criminal charges after he allegedly heaved a garbage can at a bank teller who declined to oblige him $20,000 in cash from an overdrawn account. “Maybe I didn’t realize how deeply I was grieving,” the scion alibis. “Had Marion Barry not been my father, he still would be my hero,” says Marion Barry.

Then, from inside the house, a campaign worker yells: “Hey, Chris!”

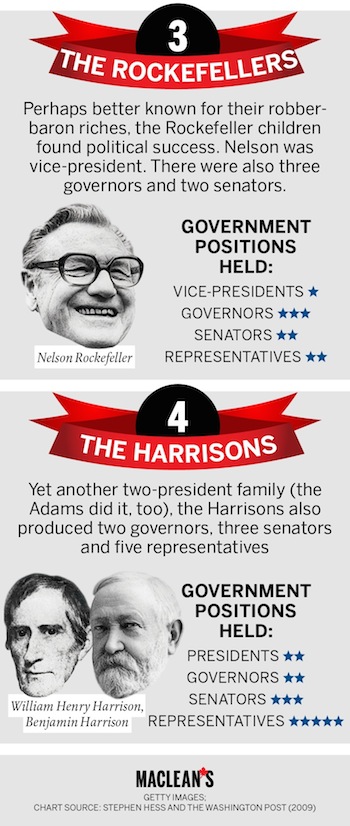

The American political landscape has changed considerably since 1856, when a crowd of Ohioans stormed the home of a young attorney named Benjamin Harrison, urging him to run for office merely because his grandfather, William Henry Harrison, had been elected president of the United States in 1840. “My ambition is for quietness rather than for publicity,” the younger Harrison protested. “I want it understood that I am the grandson of nobody.”

These days on Capitol Hill, it is rather easy to find the suggestion of a nepotistic—or at least familial—trend, without even having to invoke Hillary Clinton or Jeb Bush or Rand Paul, the Kentucky senator and Republican presidential candidate whose father sat in the House of Representatives for 22 years.

For example: on a Thursday morning in late April, the House subcommittee on health of the committee on energy and commerce is meeting to discuss the topic of “21st-century cures.” Of the 13 Democrats on the subcommittee, one is Joseph P. Kennedy III (the grandson of senator Robert F. and the son of a Massachusetts congressman), one is John Sarbanes (the son of a U.S. senator from Maryland), one is the son of a county judge in Florida, one is the son of the former Speaker of the New Mexico legislature, one is the son of a former New Jersey state senator, and two are the widows of members of Congress from California who triumphed in special elections to replace them, just as the living Marion Barry is aspiring to succeed the dead one. (Committee chairman Fred Upton of Michigan, a Republican, is the uncle of swimsuit model Kate, but this is a question of pulchritude, not politics.)

One rarely hears a Kennedy or a Bush protest, “I am the grandson of nobody.”

“I think we’ve seen more of this in the last 20 years,” says the retired Democrat whom the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture calls “the most popular Arkansas politician of the modern era.” “Or maybe it is just the 24-7 news cycle.” The man on the phone from Little Rock is not Bill Clinton—he is David Hampton Pryor, 80, Clinton’s predecessor as governor of Arkansas and a three-term United States senator whose son Mark rode his famous surname to two terms in the Senate as well. As a senator and the father of a senator, the senior Pryor speaks with authority on the subject of political families and their seemingly intractable place in American political life.

“I think we’ve seen more of this in the last 20 years,” says the retired Democrat whom the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture calls “the most popular Arkansas politician of the modern era.” “Or maybe it is just the 24-7 news cycle.” The man on the phone from Little Rock is not Bill Clinton—he is David Hampton Pryor, 80, Clinton’s predecessor as governor of Arkansas and a three-term United States senator whose son Mark rode his famous surname to two terms in the Senate as well. As a senator and the father of a senator, the senior Pryor speaks with authority on the subject of political families and their seemingly intractable place in American political life.

When Mark was a baby, did you bounce him on your knee and say, “Someday, you’re going to be a governor and a congressman and a senator just like your Daddy?” the elder Pryor is asked. “I never even thought about it,” he replies. “We’ve got three sons, but Mark is the only who chose that life. In his first race, Mark won by a big healthy vote for the Arkansas House and people said it was because of his name. Then he challenged a Democratic state attorney general and people said, ‘We’ve had enough Pryors,’ and they put Mark on the shelf. It cuts both ways.”

A century ago, president Woodrow Wilson named a new secretary of the treasury: his son-in-law. A century before that, president John Adams named a minister to Prussia: his son John Quincy, who would go on to become president himself. “The ambition is constant, and unceasing,” John Quincy Adams wrote.

This set the stage for president John F. Kennedy to appoint his brother Bobby to be his attorney general. And for William Jefferson Clinton to name someone to overhaul the nation’s health care system: his wife. And for president George W. Bush to select as his secretary of labor the wife of Mitch McConnell, the Republican leader in the Senate. And so on, ad infinitum and, to some Americans, ad nauseum.

“From 2003 to 2006, the Senate had the highest percentage of senators’ children—six —in its history,” the New York Times calculated. “The same methodology suggests that sons of senators had an 8,500 times higher chance of becoming a senator than an average American male Boomer.” Sniffed the Guardian: “The U.S. seems to be drawing its political leadership from an increasingly shallow puddle of genes.”

“With at least 18 senators, dozens of House members and several administration officials boosted by family legacies, modern-day Washington sometimes resembles the court of Louis XIV without the powdered wigs,” hooted the Washington Post.

But then a funny thing happened—the 2014 elections. Mary Landrieu, daughter of a popular mayor of New Orleans, ran for re-election to the U.S. Senate—and lost. Kay Hagan, niece of a popular governor of Florida, ran for re-election to the U.S. Senate—and lost. Mark Begich, the son of a congressman from Alaska who died in a plane crash while in office, ran for re-election to the U.S. Senate—and lost. Mark Udall, the son of a congressman and a member of the most prominent political dynasty in the American west, ran for re-election for the U.S. Senate—and lost. Jason Carter, grandson of the 39th president, ran for governor in Georgia—“The question is not about Jimmy Carter, it’s about Jason Carter”—and lost.

Yet all those Democrats on the House subcommittee on health were able to keep their seats. “The public has a way of sorting all this out. I think they generally look at the individual as an individual in his or her own right,” says the elder Pryor. The father speaks from sad experience: last November, his son Mark, the U.S. senator, ran for re-election and lost. “He not only lost it, he lost it big,” sighs Pryor. “And down in Georgia, you can’t have a better name in politics than Nunn, but Michelle Nunn, whose father was senator Sam Nunn and who is one of the most outstanding young people I’ve ever known and who would have been a fabulous U.S. senator, was defeated in the November Republican onslaught.”

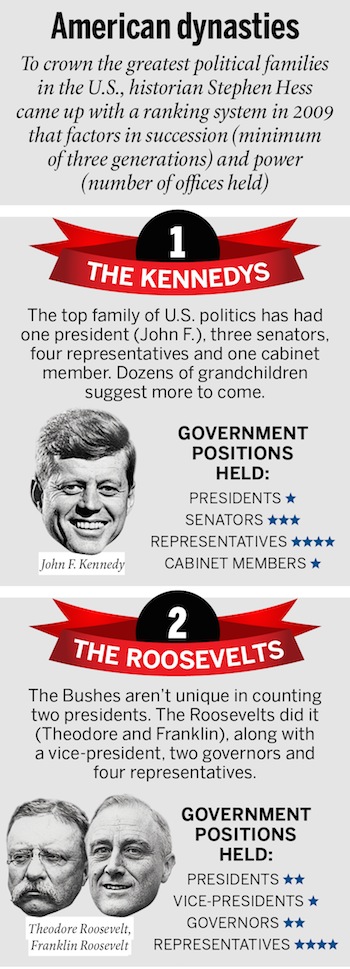

In 1966, the noted historian and presidential adviser (going all the way back to the Eisenhower years) Stephen Hess wrote a book entitled America’s Political Dynasties. Fifty years later, he’s writing it all over again. “If you look at any point in American history, you’ll find exactly the same thing,” Hess says from the Brookings Institution, where he is senior fellow emeritus of government studies. “We have had political dynasties forever, but they’re constantly changing—some growing, some dying. I think that shows the virility of our democracy.”

The 2014 wipeout of hereditary senators does not mean that the dynastic epoch is ending, Hess contends. Bakers beget bakers, and politicians—especially in gerrymandered congressional districts where family, ethnic and business roots run deep—will always beget more of the same. Witness the Frelinghuysens of New Jersey, whose sons have served in Congress for seven generations dating back to the 1770s. And all those Democrats on the health subcommittee who held their seats last fall. Yet there is not a Roosevelt or a Harrison or an Adams to be seen.

The 2014 wipeout of hereditary senators does not mean that the dynastic epoch is ending, Hess contends. Bakers beget bakers, and politicians—especially in gerrymandered congressional districts where family, ethnic and business roots run deep—will always beget more of the same. Witness the Frelinghuysens of New Jersey, whose sons have served in Congress for seven generations dating back to the 1770s. And all those Democrats on the health subcommittee who held their seats last fall. Yet there is not a Roosevelt or a Harrison or an Adams to be seen.

“Americans seem to be embarrassed that the Bushes and Clintons are once more in contention,” Hess says. “But look at where our top so-called dynasties come from—Bill Clinton came from the lower-lower-lower middle class. Hillary Rodham came from the sort of fallen middle class. The Clintons’ problem is that they only had one child!”

“I don’t know if it’s bad or good,” says Pryor. “I don’t know if you can say to families, ‘Your father was president and your brother was president and therefore you can’t run.’ I think you have to let it run its way through and let people make the decision.”

“There’s a—I don’t want to say Bush or Clinton fatigue—but the public is constantly looking across the constellation for a new face or a new name. A lot of the Tea Party appeal is based on that desire to have newness and freshness,” adds Pryor. “You know, we had a congressman from Arkansas for about 10 years named Marion Berry,” Pryor says. “And oh, that poor congressman! He spent half of every day trying to tell people that he wasn’t Marion Barry! All that just because of a name. Ain’t America great?”

Back on his late father’s front porch (the house is for sale; Marion Barry the elder was behind on his payments), Marion Barry the younger is asked about Jeb and Hillary and he answers, “All politics is like that—the same cliques, the same circles. They got people already being groomed for 2030. The real split, the real divide is between the real America and the Republicans and the business people.”

“What’s great about our political system is that we are all judged on our own merits,” Hillary Clinton said in 2008. “We start from the same place. Nobody has an advantage no matter who you are or where you came from.”

“I think this is a great American country,” said Barbara Bush, wife of a president and mother of a president, when asked about her son Jeb’s candidacy. “And if we can’t find more than two or three families to run for high office, that’s silly.”

Now, in Ward 8 in Washington, special-election night comes and goes. Two candidates run neck and neck for the seat at council, but Marion Christopher Barry isn’t one of them. He finishes a distant sixth with 460 votes out of 6,351. So much for the coattails of the “mayor for life.” But the son remains undaunted; of all his possessions, he knows that his surname is the most valuable. There will be another election in Ward 8 next November.

“This time, money spoke,” Marion Barry the younger declares. “Next time, the people will speak. My campaign for my father’s seat in Ward 8 begins tomorrow.”