How Hillary turned the U.S. election into a showdown over gender

As she takes on the divisive Trump, Hillary Clinton harnesses her sex as campaign strength

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton receives a warm reception from a capacity crowd at the Exposition Center of the North Carolina State Fairgrounds in Raleigh, N.C., on Wednesday, June 22, 2016. (Chuck Liddy/Raleigh News & Observer/Getty Images)

Share

Hillary Clinton has just taken the stage at the Exposition Centre in the North Carolina Fairgrounds in Raleigh-Durham before a rapturous crowd: young, old, male, female, black, white, Hispanic, babies in strollers, elderly in wheelchairs. It’s late June, a month from the Democratic National Convention, and the Clinton campaign has chosen the economically embattled swing state to unveil her economic plan. North Carolina matters; Barack Obama won it by 0.32 per cent of the vote in 2008; Mitt Romney took it in 2012 by a slightly higher margin.

The space, typically home to gun fairs and scrapbooking festivals, is festooned with American flags and “Stronger Together” banners. Security is tight and ominously present. Bomb-sniffing dogs, body sweeps, Secret Service—marked and unmarked—monitor a crowd primed by hours of pop female empowerment anthems: Spice Girls’ “Wannabe,” Shania Twain’s “Man! I Feel Like a Woman,” Katy Perry’s “Roar”—and a parade of testimonials from politicians and common folk celebrating the woman touted to be the “first female president of the United States.”

Once on stage, Clinton basks in the adulation as she energetically outlines her plan in big rhetorical strokes: a national minimum wage, making college debt-free, making companies share profits with employees, and corporations and the one per cent paying their fair share of taxes. Throughout, she weaves the personal with political as only a former FLOTUS, mother, senator and former Secretary of State could. “If you notice anything different about me today, it could be because now I’ve got double the grandmother glow,” she says to cheers, referring to her daughter, Chelsea, giving birth days earlier. She pivots quickly: “I believe with all my heart that you should not have to be the grandchild of a former president or Secretary of State to have every opportunity available to you in this country.” The crowd erupts.

MORE: Why the phrase ‘spicy boi’ is flooding Hillary Clinton’s social-media accounts

Presenting herself as a champion of women and families, she flouts her Republican opponent’s claim that she’s capitalizing on her sex: “And you know, whenever I talk about these family issues, Donald Trump says I’m playing the woman card. Right? Well, you know what I say, ‘If fighting for child care, paid leave and equal pay is playing the woman card—’ ” she pauses to cue an audience to shout in unison: “Then deal me in!”

As Clinton leaves the stage to Taylor Swift’s “Shake it Off” she’s swarmed by people wanting selfies. “She should be proud to play the woman card,” says Charles Keeling, a 69-year-old white man. “Hillary’s a friend to the women of America.” He and Clinton “see pretty much eye to eye,” he says: “She speaks to my priority issues like climate change and gun control.” Emily Giangrande, 22, who just completed a graduate degree, wants her dog-eared copy of Clinton’s 2003 memoir, Living History, signed. “I’ve been a Hillary Clinton supporter since middle school,” she says. That Clinton is a woman is part of her appeal: “It’s confounding that we’ve never had a female president,” she says. “It’s time we caught up with the world.” Her 45-year-old mother, Geri Maddox, agrees: “Hillary has paid her dues.”

That the first female U.S. presidential candidate for a major party has made gender an election issue is inevitable. But Clinton’s candidacy highlights another truth: American presidential elections have always been about gender—only male gender, as Jackson Katz points out in the recently published Man Enough?: Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, and the Politics of Presidential Masculinity. From Ronald Reagan vs. Jimmy Carter onward, elections have been unspoken masculinity contests, debates about American manhood waged exclusively by white men until Barack Obama, Katz argues. The tough guy with certitude has prevailed; the nuanced or indecisive is emasculated, viz. Michael Dukakis or John Kerry. Sports, military, even cowboy imagery dominate: Ronald Reagan on his horse, Barack Obama on the basketball court, Donald Trump in his red baseball cap.

Were this a “normal” election—one in which Clinton was facing a moderate Mitt Romney-style Republican opponent—she’d be at a major disadvantage. Not only is she a woman but more than half of Americans (53 per cent) hold an unfavourable opinion of her (Clinton’s popularity has taken a nose-dive every time she has sought power). She’s also been dogged by accusations of greed and corrupt behaviour, giving rise to Trump’s “crooked Hillary” taunt.

But in Trump, who’s prone to sexist, racist remarks, and who plays the male gender card even more overtly, Clinton’s been handed a perfect foil, a gift of sorts. “Trump’s entire candidacy is based on the idea that the solution to our national problems is to put a tough, no-nonsense white man back in the White House,” says Katz. It’s all about his manhood—and by definition, theirs.”

That in turn frees Clinton to make gender politics a campaign issue in a way that otherwise would have seen blowback. Polling bears this out. As of early July, Clinton was ahead by seven points, largely on her strength with female voters; its the highest level of female support of any candidate in more than four decades and the widest gender gap recorded —24 percentage points in the latest Pew Research Center Poll. These voters are not only Democrats: Republican media strategist Mindy Finn has likened Trump to an “abusive boyfriend.” In early July, Republican Women for Hillary formed: “Vote to make sure Republican women don’t get Trumped,” its Facebook page proclaims. Trump, meanwhile, leads, by a narrowing margin, among white men: 50 per cent to Clinton’s 41 per cent.

RELATED: With the Democratic nod, Hillary finally gets her moment

The result is an unprecedented gender-centric showdown between characters who’ve achieved near mythological cultural resonance: the boorish, blustering billionaire and former reality-TV star who treats women as objects versus a woman whose 25 years in the public eye has rendered her protean, a shape-shifter who is variously a workhorse feminist advocate, a Lady Macbeth-style schemer, an accomplished stateswoman, a Wall Street shill and a master of Washington cash-for-access culture.

In the introduction to a new book of essays with the telling title Who Is Hillary Clinton? Two Decades of Answers from the Left, Katha Politt calls Clinton “a test of our attitudes—including our unconscious ones—about women, feminism, sex and marriage, to say nothing of the Democratic Party, progressive politics, the United States and capitalism.”

The election promises to be a watershed, says Katz: “It’s as close to a national referendum on the state of women’s advancement as you could possibly get.” Clinton frames it in bigger terms, with the country, a polarized tinderbox, at stake. “This election isn’t about the same old fights between Democrats and Republicans,” she said during speech at Planned Parenthood in June. “It’s about who we are as a nation.”

As contests of masculinity, presidential elections are about creating heroes, not policy. Clinton becoming the first female U.S. president isn’t enough, however. She has to defeat a foe representing a threat to both women and America, to make Trump “the loser” he so despises. Women are at risk, she told the crowd at Planned Parenthood. Trump “wants to roll back the clock . . . Back to the days when abortion was illegal, women had far fewer options, and life for too many women and girls was limited.” And she’s the one to vanquish him, she boasts. “We’re not just going to break that highest and hardest glass ceiling. We’re going to break down all the barriers that hold women and families back.”

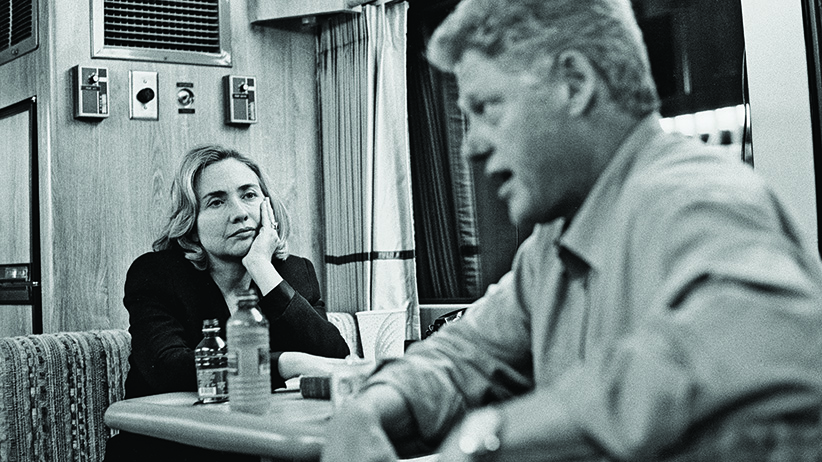

The email scandal that saw Clinton and her aides rebuked by the head of the FBI for being “extremely careless in their handling of very sensitive, highly classified information” when she was Secretary of State, was the latest of a decades-long parade of controversies she has stoked since arriving on the national stage. The first was on a 60 Minutes interview during the 1992 presidential election, in which she sat beside her husband to address claims he’d committed adultery (there was no admission, only a call for privacy). Hillary Clinton incited fury with her remark: “I’m not sitting here as some little woman standing by my man like Tammy Wynette. I’m sitting here because I love him and I respect him and I honour what he’s been through and what we’ve been through together, and if that’s not enough for people then heck, don’t vote for him.” The comment, which overlooked the fact Wynette was married five times, revealed defiance unseen on the U.S. political stage: an alpha wife bristling against the conventional beta role.

She fanned the flames later that year after then-California governor Jerry Brown accused her husband of improperly benefiting from his wife’s legal practice in his capacity as Arkansas governor, charges never substantiated. “I suppose I could have stayed home, baked cookies and had teas,” Clinton said, outraging homemakers and winning the label “smug bitch.” (Media failed to report her full statement: “The work that I have done as a professional, a public advocate, has been aimed . . . to assure that women can make the choices, whether it’s full-time career, full-time motherhood or some combination.”)

The statement is befitting a woman born in 1947, raised in a middle-class household in a Chicago suburb, who came of age amid the social ferment of the ’60s: civil rights, the women’s movement and belief a new world order would bring equality to all. She attended Wellesley, an elite women’s college, in 1965, becoming class president. In 1969, she entered Yale Law School. There she’d meet Bill Clinton, the “Viking” from Arkansas. Hillary was the star; she introduced herself to Clinton in 1970 after he had followed her around campus for months. After graduation, she worked for the Children’s Defense Fund before marrying in 1975 and moving to Arkansas. She joined a prestigious law firm, becoming its first female partner, and continued to work after Chelsea was born in 1980. She kept her name after marriage, which saw her husband ridiculed when he ran for governor in 1978; he won, then lost in 1980; when he ran again in 1982, his wife was known as Hillary Rodham Clinton. (She dropped Rodham when she ran for president in 2008.)

Refusing the power-behind-the-throne role played by first ladies from Edith Wilson to Nancy Reagan, Clinton presented herself as an equal partner, a “two for one.” She moved her office to the West Wing and waged an unsuccessful bid for universal health care. Her ambitions were criticized by her husband’s foes and the media. In 1995, the satiric magazine Spy presented her as an androgyne, female on top, male below. (Spy also famously dubbed Trump a “short-fingered vulgarian.”)

Clinton rejected the traditional wife role but proved adept at dipping in and out of the script when needed. After her health-reform plan failed, she churned out first-lady feel-good books, including It Takes a Village and Dear Socks, Dear Buddy. She even agreed to a retrograde chocolate-chip-cookie bake-off with Barbara Bush during the 1996 presidential campaign; Clinton won (rolled oats were her secret ingredient). And she stood by her man during the scandal and impeachment arising from his relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. In 2000, roles were reversed: her proximity to presidential power helped her become a U.S. senator in 2000 and secure an $8-million advance for her autobiography.

Throughout, the Clintons’ 41-year marriage, often described as an “arrangement” as if other marriages are not, garnered speculation. In Gail Sheehy’s Hillary’s Choice, Clinton revealed she was attracted to Bill Clinton because “he wasn’t afraid of me.” At a 2014 TED Talk, the anthropologist Helen Fisher suggested that the couple defied social norms: Hillary Clinton fit the “testosterone” neurochemical profile (logical, competitive, direct, demanding), while Bill was “estrogen” (a negotiator, philosopher king, good with language).

The Clintons have survived a host of scandals: Whitewater, Travelgate, the suicide of White House counsel and Clinton friend Vince Foster, Lewinsky and, more recently, claims that the Clinton Foundation launders money and had undue influence at the State Department. But accusations of carelessness, greed, arrogance, and seeing themselves above the law linger. In 1998, Hillary Clinton blamed a “vast right-wing conspiracy” for creating the Lewinsky disgrace without evidence. Yet she is no doubt a target. The Republican-led investigation into the 2012 attack in Benghazi, Libya—where four Americans were killed and Clinton’s State Department was blamed for not properly protecting installations—lasted longer than the investigation into 9/11, with no smoking guns produced. Yet Benghazi, not the capture of Osama bin Laden, remains her legacy. High speaking fees she commands have also led to charges she’s in Wall Street’s pocket, yet 20 organizations paid her more. With the exception of one speech to Deutsche Bank, Clinton received $225,000 each for eight Wall Street speeches. She received $275,000 from Canada 2020, the Vancouver Board of Trade and the Board of Trade of Metropolitan Montreal, which would suggest, if anything, she’s in Canada’s pocket.

Discomfort with Clinton’s ambition is evident in her approval ratings, which hit an all-time high of 67 per cent in December 1998 after the Lewinsky scandal, when she was the humiliated wife. When she asked for power —introducing health care reform to Congress, declaring her first Senate run—her favourables plummeted. They’d rise after she withdrew from the 2008 presidential race and stayed high, peaking when she stepped down as Secretary of State; they dropped when she declared her second presidential run.

In a telling scene in August 2001, Clinton was among the 12 of 13 female senators interviewed on Larry King Live. King asked who had presidential aspirations, a question never asked of male senators. None said yes. Even today, Clinton’s Twitter handle lists the personal first: “Wife, mom, grandma, women+kids advocate, FLOTUS, Senator, SecState, hair icon, pantsuit aficionado, 2016 presidential candidate.” Given a body of research showing discomfort with high-achieving women, that’s not surprising: “Women are expected to be nice, warm, friendly, and nurturing,” concluded sociologist Marianne Cooper, a Stanford professor and lead researcher for Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In, in a 2013 study published in the Harvard Business Review: Those who act assertively, competitively or exhibit decisive leadership, are “deviating from the social script,” Cooper wrote. “We often don’t really like them.” Tellingly, the 2015 book Unlikeable: The Problem with Hillary Clinton, written by conservative Edward Klein, reported Steven Spielberg was enlisted to make the candidate cuddlier; she fired him.

Calls for Clinton to be “authentic” also are unreasonable, says Katz: “What does it mean to be authentic when you’re under the glare of public scrutiny she’s been under since she was first lady? Everything is a performance at that point.”

Clinton’s performance now is focused on harnessing her sex, and female accomplishment, as a strength, contrary to the tack taken in 2008 when advisers recommended she downplay the historical import of her run. “I have to say, pink never looked so good,” Clinton told a crowd at Planned Parenthood in June.

It’s a stragetic counterpunch to Trump, the former owner of the Miss USA and Miss Universe pageants, and his clarion call to downwardly mobile white men, one that taps into a malaise decades in the making. In her 1999 book, Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, Susan Faludi traced the decline of traditional postwar masculinity resulting from globalization, downsizing and the women’s movement. The resulting loss of purpose and sense of betrayal gave rise to so-called “Angry White Man” politics seen in the Promise Keepers movement, she wrote. Faludi presciently observed a shift to an “ornamental” or celebrity culture that measures masculine success in terms of fame and wealth, factors that paved way for a non-politician candidate like Trump, who has the advantage of not being part of the nation’s political wallpaper, with no record to attack, unlike Clinton. Stiffed was published before 9/11, and the resulting xenophobia, nativism and fear that the Trump campaign also stokes with messaging drawn directly from white-supremacist forums.

“Make America great again” is code for “white men who feel betrayed by the system,” Katz says. “Trump rejecting ‘political correctness’ gives cover to publicly criticize women and people of colour and do it forcefully rather than cowering and being fearful [that] people will call him names. He doesn’t care if he’s called racist or sexist.” The resentment he stokes is evident in “Trump that bitch” T-shirts worn by supporters, 47 per cent of whom are “mostly voting for him,” with 39 per cent mostly voting against Clinton, according to a July USA Today/Suffolk University Poll. (Almost three-quarters of Clinton supporters say they’re mostly voting for her.) It’s evident too in Trump’s defence of his “manhood” during the Fox News Republican debate when he responded to taunts about his hands: “If they’re small, something else must be small,” he said, “I guarantee you there’s no problem. I guarantee.”

That presidential elections are traditionally manhood contests gives Trump ground to say Clinton “doesn’t even look presidential!” as he tweeted during her Raleigh speech. Sarah Palin also employed gender-laden language in July: “You seen some of the left’s rallies? Cranky. Demanding. Shrill.” But in making history as the Democratic nominee, Clinton has begun redefining the iconography of the American presidential race—and finding her more authentic alpha voice in the process.

A new Hillary, a warmer Hillary—or at least a Hillary warmed by hard-won success—entered Brooklyn Navy Yard alone on June 7 to deliver her acceptance speech. Eschewing the traditional family backdrop tableau (they’d join her later), she greeted and hugged supporters before taking the stage, arms outstretched as if hugging the nation. Hours earlier, the campaign released “History Made,” a video that placed Clinton’s victory within a continuum of historic female advancement: the Seneca Falls convention of 1848, which passed a resolution in favour of women’s suffrage, and alongside trailblazers Gloria Steinem, Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg and Shirley Chisholm, who ran for president in 1973, the first woman to do so. “We need to learn from the women of the world who blazed new paths,” Clinton says in the voiceover.

She presented herself as a trailblazer and protector: “As your president I will always have your back,” she said. The cover of the next week’s New Yorker depicted Clinton in the boxing ring, a contender, reflecting the paucity of gender-neutral imagery surrounding political victory.

The maternal fighter metaphor continued in new commercials for Clinton highlighting her lifelong support of children’s issues. She also engaged in female bonding with progessive Sen. Elizabeth Warren, “a pair of tough broads, teaming up to chew up and spit out Donald Trump,” as journalist Rebecca Traister put it. Her Twitter feed has become more aggressive. “Delete your account,” she ordered Trump after he tweeted: “Obama just endorsed Crooked Hillary. He wants four more years of Obama but nobody else does!”

Clinton clearly revels in goading Trump, whom she calls “Donald” as if referring to a wayward child. Last week, in front of one of Trump’s shuttered Atlantic City casinos, she attacked the basis of his masculine cred, his wealth, pointing to his record running up debt, defaulting on loans and employees, and bankrupting companies. The campaign has an arsenal of recyclable one-liners. In Raleigh, Clinton called Trump the “self-proclaimed king of debt,” taking a shot at his bankruptcies: “We need to write a new chapter in the American Dream—and it sure cannot be Chapter 11.” His reality-TV show history is also fodder: “Maybe we shouldn’t expect better from someone whose most famous words are, ‘You’re fired!’ ” Clinton said in Raleigh. “Well, here’s what I want you to know, I do have a jobs program, and as president, I’m going to make sure you hear, ‘You’re hired!’ ”

Trump’s emotional volatility, a trait historically associated with women, is another target. “Imagine if he had not just his Twitter account at his disposal when he’s angry, but America’s entire arsenal,” Clinton has said. It’s touchy territory for Clinton, who has been attacked for her support of the invasion of Iraq and backing escalation of the war in Afghanistan. Katz sees her hawkish stance as necessary, even strategic: “You have to be living in a complete fantasy world to think that a woman could get within one step of the presidency without firmly establishing her masculine credentials as the potential commander-in-chief.” Last week, Clinton was the more active candidate in addressing racial violence, speaking at the African Methodist Episcopal Church community in Philadelphia. Trump was uncharacteristically muted, issuing a Facebook message and taped video.

Clinton is rewiring the political landscape in other ways. Last week, the New York Times reported she plans to strike gender parity in a cabinet that is currently 35 per cent female. She wants to bond with Republicans over drinks, a more-gender neutral setting than the traditional golf game. Tellingly, her female-centric Instagram feed features a photo of her raising a pint of Guinness among men in Ohio, a nod to the maxim that people vote for a president they want to have a beer with. The site also includes a plea for bipartisan unity: there’s a post of a gracious letter George H.W. Bush left Bill Clinton when he became president. “That’s the America we love,” she wrote.

“Republican Women for Hillary” (hashtag: #GOPWITHHER) have responded in kind. “Our decision to support Hillary Clinton is not a gender thing, though it’s wonderful she’s a woman,” Meghan Milloy, who’s on the group’s steering committee, tells Maclean’s. The 29-year-old, who works for a conservative think tank, says Trump’s “racist, misogynist and bigoted” comments scare her. “His lack of experience and the way he flies off the handle is concerning,” she says, adding that the group has been criticized for turning their back on the party. “My response is, ‘No, we’re doing our party a favour. This is the party of Lincoln and a party for the people. We don’t want to be rebranded the party of Trump’.” Hundreds have contacted them, she says; they met with the Clinton campaign last week. Hers is not purely an anti-Trump vote, Milloy says: “I have enough common ground with [Clinton] that it’s a vote of support for Hillary.” Clinton’s experience is a plus: “You can disagree with Hillary all you want but she’s been in the situation room; she knows how things work.”

That means she also knows she has a fight before her, despite the fact that Trump’s campaign is in a shambolic state—48 per cent of Republicans want another candidate, according to a June CNN poll—and that more of the electorate (60 per cent) dislike him more than her. That a candidate known for hateful, false, often incoherent statements is only behind seven points reflects a country severed in a true gender war. Last week, Clinton and Obama were back in North Carolina, in Charlotte. Trump was in Raleigh, where things turned ugly; his supporters called to “Hang that bitch!” and “Hang Hillary!” When a mosquito landed by Trump he became discombobulated, yelling, “I don’t like mosquitos!” He then addressed it: “Hello, Hillary,” as the crowd roared.

It was a different mood outside the Exposition Centre in June, where vendors sold Hillary T-shirts and buttons with positive messages: “Love trumps hate,” “I’m with her,” and “Hills yes!” Yet on the edge of the parking lot two girls—no older than seven—with sticks bashed a piñata shaped like a tiny Trump. A crowd gathered to egg them on as a cameraman filmed it. Love may trump hate, rhetorically speaking, but this is a political war, one whose stakes have never been higher.