Is Marco Rubio the real deal?

Marco Rubio has what it takes to be America’s president. But first, he needs to triumph in a crowded, histrionic Republican field.

Share

Toni Ledbetter and Tony Ledbetter are relaxing on a divan in a hotel lobby just outside the gates of Walt Disney World. The Florida sun is setting in a mellow, mousey sky, and the Ledbetters—they are mister and missus, from Daytona Beach—are talking about the 2016 election while they wait for dinner and a speech by Florida’s (presumably) favourite son, the young, handsome U.S. senator and Republican presidential candidate and cheerleader’s husband and father of four: Marco Antonio Rubio.

Tony Ledbetter is the rainmaker of the Republican party machine in Volusia County. He and Toni operate a business that manufactures golf visors, which, they are proud to say, are made in the United States.

Marco Rubio, one of more than a dozen Republican aspirants still standing with the Iowa caucuses only 10 weeks away, often characterizes himself as a champion of small businesses, such as the one the Ledbetters maintain. His stump speech is heavy with references to his father’s arduous path as an immigrant Cuban who worked as a banquet-hall bartender in Miami and Las Vegas, and his mother’s labours as a hotel chambermaid. The senator’s own travails with US$100,000 in law-school debt and maxed-out credit cards have been both his burden and his boast.

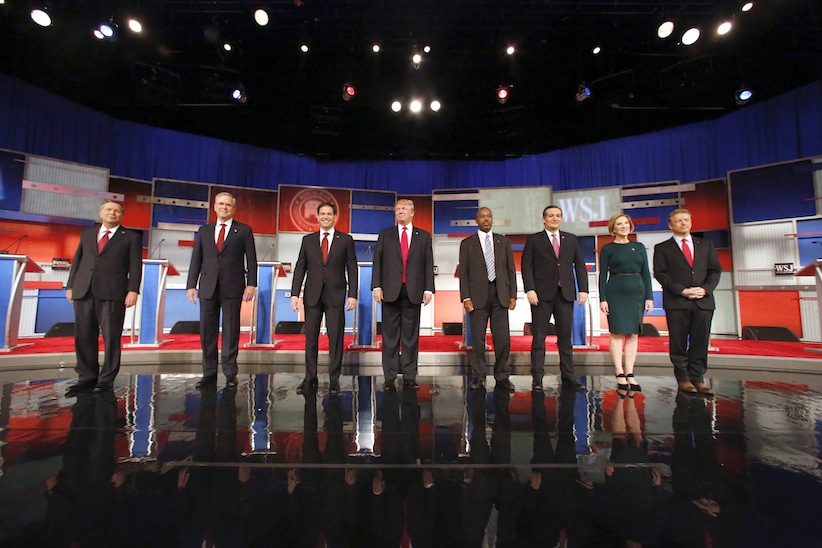

In the most recent debates among the Republican front-runners, Rubio has been hailed for his crisp, direct, well-formed answers to questions of economic policy, and his smackdown of his erstwhile mentor, former Florida governor Jeb (“the Joyful Tortoise”) Bush.

This has boosted Rubio’s standing in the all-important Iowa surveys to as high as one voter in seven. Many of the experts who have been predicting the imminent collapse of Donald Trump and Dr. Ben Carson for the past six months now hail Rubio as the “establishment” candidate most likely to prevail when they do. The 44-year-old paints himself as the generational alternative to 68-year-old Hillary Clinton, as a modernist who understands the epochal economic transformation being wrought by disrupters such as Amazon and Uber, and as a sane voice amid the histrionics of the Republican field, with no intention of building any huge, magnificent walls.

Tonight, he is to speak to an assemblage of more than 900 Florida Republicans to kick off their “Sunshine Summit.” So will former vice-president Dick Cheney. “We love Dick Cheney!” the Ledbetters jointly cry. Tony, the husband, hasn’t been this heated up politically since Ronald (“I felt like he was part of the family”) Reagan left the White House in 1989. And Toni not since 1964 and Barry Goldwater. Unfortunately for Marco Rubio in 2015, neither Ledbetter is fired up for him.

Tony: “We’re for Trump. The American people like Trump because he doesn’t owe anybody anything. And when he gets to D.C., he won’t owe anybody anything.”

Toni: “I grew up in Texas—I know illegal immigrants . . . It’s time for them to go home. If Donald can figure out a way to put ’em on a bus, go for it!” She continues: “Marco Rubio is very pretty, like your new guy, Pierre, in Canada. All the women will vote for him.”

“What would Marco Rubio have to say tonight to make you vote for him in the primary?” they are asked.

Tony: “No matter what he said, I don’t know that I’d believe him.”

Toni: “We in the Tea Party worked so hard for Marco Rubio . . . We got him elected, and then he turned his back on us with amnesty for the illegals. The guy just disappeared from us since 2010.”

Ozzie Martinez dashes into Havana’s Café in Bermuda shorts and a hurry. This is his daily routine: a quick break for a cortadito, then back to his post as bell captain at the Best Western on Palm Parkway, between Sea World and the Magic Kingdom.

Ozzie Martinez dashes into Havana’s Café in Bermuda shorts and a hurry. This is his daily routine: a quick break for a cortadito, then back to his post as bell captain at the Best Western on Palm Parkway, between Sea World and the Magic Kingdom.

Havana’s Café is busy at lunch hour with Latino families, local gourmands and tourists. On the menu are such classics as ropa vieja, which is a shredded-beef stew. Martinez left the real Havana in 1998; he obtained a tourist visa to Costa Rica and never went back. He is Marco Rubio’s father refracted in the prism of the 21st century, a hotel employee trying to make ends meet for his family. But he won’t be voting for Rubio when Florida stages its primary on March 15.

For president, he is strongly for Hillary Clinton, or even her rival, Sen. Bernie Sanders, if it comes to that. “The Republicans don’t have anything for the middle class and the poor people,” Martinez says. “The Republican philosophy is, if you give a poor person one dollar, he’ll spend it on nonsense. That’s just not right.”

Kathy Polanco owns Havana’s Café. She was born in New York City but her parents came from Cuba just after Fidel Castro declared himself a communist. “Everything was left behind,” Polanco says. “But I wasn’t brought up to hate Fidel like the Cubans in Miami. My parents didn’t have that hate.”

Rubio, she says, “is an eager young man, very bright, with huge charisma. But I think he lost his principles because of his party. He wants to repeal Obamacare, but if you try to tame a dragon that is lucrative for a lot of people, you’ll find it is a very big dragon to tame.” So she is “tending toward Hillary, not just because she’s a woman, but because I think she’ll make a difference.”

Polanco used to be a Republican, but she came to feel “that they were moving in a different direction. They have to be more sensitive to a nation that has lost its way.”

“Wouldn’t you be proud to have a Cuban president?” the Cuban-Americans are asked. “Cuban presidents are Fidel and Raúl,” Martinez replies. “Those guys are Cuban presidents.”

Rubio and his wife, Jeanette, walk into a conference room at a magnificent resort hotel on Orlando’s Shingle Creek. It is the morning after the supper-hour fete with Dick Cheney, and Rubio is warming up a few hundred of his devoted supporters before his plenary address to the Sunshine Summit. “Most of the people who thought I couldn’t win were in my own house, and four of them were under the age of 10,” he jokes, flashing that smile.

(It is unfair to label Jeanette Dousdebes Rubio as merely “a former cheerleader and calendar model.” Her stint with the Miami Dolphins was brief, and she has raised Anthony, Dominick, Daniella and Amanda while her husband commuted from Miami to Tallahassee to Capitol Hill. If Marco is elected, the Rubios will be the first parents to bring four school-age children to live in the White House since Teddy and Edith Roosevelt in 1901.)

A moment later, the senator is on stage in the Panzacola ballroom, selling himself as the avatar of “a generational choice about what direction our country will take,” vowing reflexively “to repeal and replace Obamacare,” and lamenting that “Americans who hold basic values feel like outsiders in their own country.” (Rubio’s appearance at the Sunshine Summit occurs almost simultaneously with the terrorist attacks in Paris. Within hours, he will flip-flop on his previous position for a careful screening of Syrian refugees and will call for a “pause” in the influx.)

He offers himself as the champion of striving immigrants—“the people who clean your rooms and park your cars”—and jibes that “some came here fleeing socialism in Venezuela; some came here fleeing socialism in New York.”

“I just lost the New York primary,” he laughs. Then, earnestly: “I feel personally called to this, passionately.”

“We are running out of time,” Rubio says.

Rebecca and Daniel Broyles stand behind the counter of a home-furnishings shop called Foreign Accents in the Orlando district of SoDo (south of downtown). Their emporium features an eclectic assortment of credenzas, lamps and urns, many of them personally hauled up from Mexico in the Broyles’s Ford Expedition.

In his recent book American Dreams: Restoring Economic Opportunity for Everyone, Rubio specifically cites the Broyles’s struggles during the Great Recession as evidence of how “our political leadership—from both parties—is failing families who can’t afford to influence the agenda in Washington.” The Broyles, we learn, maxed out their credit cards, got slammed by Obamacare premiums, were victimized by a faceless megabank, and “feel the system is stacked against them.”

“With three boys who depended on them,” Rubio writes, “they prayed every day that God would reveal the right way forward.”

The anecdotes in Rubio’s book are true, Daniel Broyles tells Maclean’s. “I thought we were middle class,” he shrugs. “But then I see the changes of the last seven years that all seem to favour the handout class, where everything is given to you and you’re happy to get a free cellphone and government-supplied health care.”

“I think our core values are the same as Marco’s,” Rebecca says.

“We like Marco Rubio a lot, and not just because of meeting him,” Daniel adds. “But I’m not throwing any stones at Trump.” In fact, despite being held up—in print—as the very Americans whom Marco Rubio pledges to help, they are both undecided.

“Did Rubio buy anything when he was in your shop?” the couple is asked. “You know what? He didn’t,” answers Daniel. “I’m not a very good salesman.”

In a press conference following his address to the Sunshine Summit, Rubio is buffeted by questions about his membership in the “gang of eight”—the senators from both parties who tried two years ago to construct an immigration-reform bill that would have provided a path to legal residence for this country’s 12 million undocumented banquet-hall bartenders, hotel chambermaids, etc. (They failed utterly, but the attempt was enough to equate Rubio with the “amnesty” that Tea Partiers such as the Ledbetters abhor.)

“The biggest lesson of 2013, for me, is how little Americans trust the force of law,” Rubio testifies. At the same moment that Rubio is trying to explain away his alleged waffling, Ted Cruz, the Alberta-born, Texas-raised junior senator from Texas, is pacing the stage in the Panzacola ballroom. Cruz has lately been excoriating the Floridian for his lily-livered compassion toward law-breaking wetbacks. On Day 1 of a Cruz presidency, the Texan chimes, he would abolish the Internal Revenue Service, “padlock that building,” and relegate its workers to the Mexican border.

“Imagine that you have travelled thousands of miles across the desert,” Cruz delightedly proclaims, “and you swim across the Rio Grande, and the first thing you see is 90,000 IRS agents. You’d turn around and go home!”

“I’m puzzled and, quite simply, surprised,” Rubio is saying across the hall, “because Ted’s position is not that different from mine.”

Is there anyone in Florida who will vote for Marco Rubio? Yes, at least two.

Bessie Thrasher of Port Charlotte, Fla., who describes herself on her business card as a “woman extraordinaire,” is milling about the Disney Contemporary Resort. She is with her pal Barbara A. Stephens, who is the president of the Central Pinellas Republican Club, over in Seminole on the Gulf of Mexico side of the state. “Marco is extremely intelligent. He knows what’s going on nationally, internationally and locally,” says Stephens.

Thrasher: “We need a moderate conservative with a broader platform like Marco to reach more people.”

Stephens: “He is a moral man, a man of integrity. He has a logical immigration plan that will pull it all together. Ted Cruz is not as electable.”

Thrasher: “Marco had such a humble beginning.”

Stephens: “He is very articulate and young. The word that comes to mind is ‘Reaganesque.’ ”

Update