President Biden and a world of trouble

Paul Wells: The crises are stacked up outside the Oval Office. Biden’s advantage will be knowing that nothing will be given to him simply because he’s a fresh face.

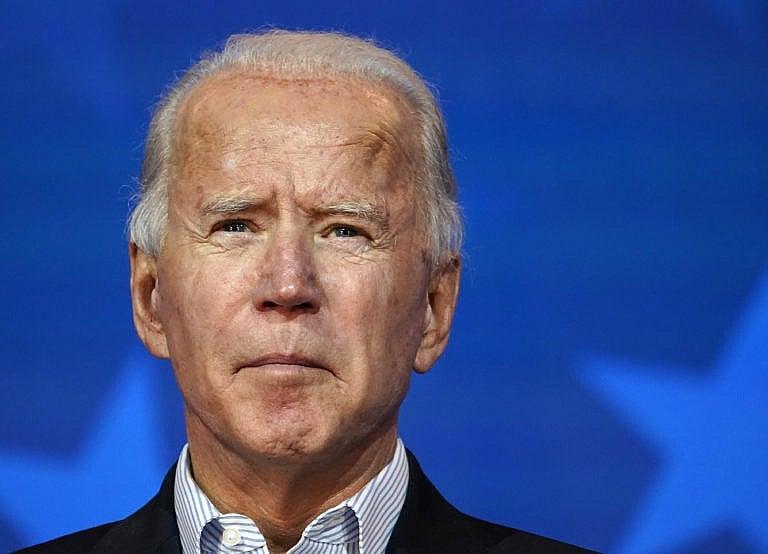

Biden prepares to speak at The Queen theater on Nov. 05, 2020 in Wilmington, Delaware (Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Share

After all it would not have been fitting if the presidency had come too easily to Joe Biden, because so little ever has.

He was born to a wealthy family fallen on hard times. For years his family lived with his mother’s parents. In school he stuttered so badly that once even a teacher mocked him. He went to ordinary schools and excelled in modest ways. Six weeks after he won a Senate seat nobody thought could go to the Democrat, his wife and daughter died in a car crash. Many years later a son died of cancer. These are the real things that weigh on a man’s thoughts even when the headlines are about other things.

He has been running for president since before there was an Internet, sabotaged his own first campaign with clumsy plagiarism, faltered repeatedly after, backed regretfully away from running at what should have been the natural moment, in 2016 at the end of his vice presidency. He’s an old man now, intermittently persuasive, less sure of himself than before. Have him sweep to power in a night? That’s not how you write this character. He needs to struggle.

He will get plenty of opportunity. On Thursday the United States recorded 1,127 deaths from the coronavirus. The deaths are coming at the rate of a 9/11 every three days or so, as they have for months. Winter will be half done before a Biden administration gets to try its hand at mastering a virus that has stumped better leaders than Donald Trump around the world. Too many people aren’t working, racism and mob rule have had much too long a day in the sun, and any cliché you might want to press into service about America’s best days following its darkest hours rings hollow, given the scale and number of the crises that beset our neighbour. It will take more than a casting change at the White House to get ahead of these demons.

But a casting change is what we’ve got, and it will have to be the basis for whatever comes after. The best modern parallel to a Biden presidency is probably Gerald Ford’s. It’s a rickety analogy, all wrong on structure, maybe closer in moment and tone. Ford replaced a president who had resigned in disgrace. Biden succeeds one who didn’t have enough class to do the same. Ford never sought national office: not only did his name never appear on a ballot as a presidential candidate, he never ran for the vice presidency either. Biden’s been far more openly ambitious. And Ford succeeded a president from his own party, unlike Biden. But the 46th president will face some of the challenges that landed on the desk of the unready 38th.

Ford understood that part of his job was to cool things down. A crisis always leaves too many people behind who have learned to enjoy shouting; they need to re-learn, by executive example, the value of a conversational tone. Ford had to rehabilitate discredited institutions. This cannot be done from a central office. It needs strong managers with autonomous authority in a hundred places. Two of the most insightful critiques of the Trump presidency, Michael Lewis’s Fifth Risk and Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny, were reminders of the value of staffing (Lewis) and of independent judgment even if it means telling a leader he’s wrong (Snyder). Their lesson amounts to this: A Biden presidency had better not be a Trump presidency that obsesses over different targets. Its business is with the American people, not with settling scores. There are courts. A president who doesn’t try to run them would be another pleasant change.

A calmer tone should not be the same as an empty agenda. Too many people seemed happy with a Senate that, if it winds up with a Republican majority (it’s way too early to know), would look like a pretext for a do-nothing presidency. Too many in the Democratic Party’s Washington lifer set view its young radicals as trouble-makers. They don’t have to be. They’re not wrong about a lot of the nation’s problems, and Joe Biden, who got elected to the Senate on an antiwar, pro-environment agenda when he was younger than Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is today, should remember how that feels.

Biden arrives in his office with the great advantage of knowing that nothing will be given to him simply because he’s a fresh face. He knows, from long experience that has seen him fail as often as succeed, that an announcement isn’t a result and a tweet isn’t an argument. He will not be impressed by glad-handers who are bored by process, because the Senate is a school of process.

It will have its glorious days. Every presidency does. But the crises are stacked up outside the Oval Office like cordwood. A virus that won’t go away, a population already tired of fighting it. A nervous world of shell-shocked allies and emboldened enemies. Democratic freedoms challenged everywhere in ways the 101st Airborne Division can’t remedy. A shaken economy, rampant injustice, industrial decline, all the problems Donald Trump was hired to fix that he ignored or goosed instead. Millions who will miss Trump and mistrust Biden. Hundreds, in every corner of the Republican Party, who will use Trump as a model to emulate. A perilous fight. But Joe Biden has known a few of those since his schoolboy days staring into a mirror, re-learning how to talk. Now at last, later in life than any president before, he gets to test himself against the moment.