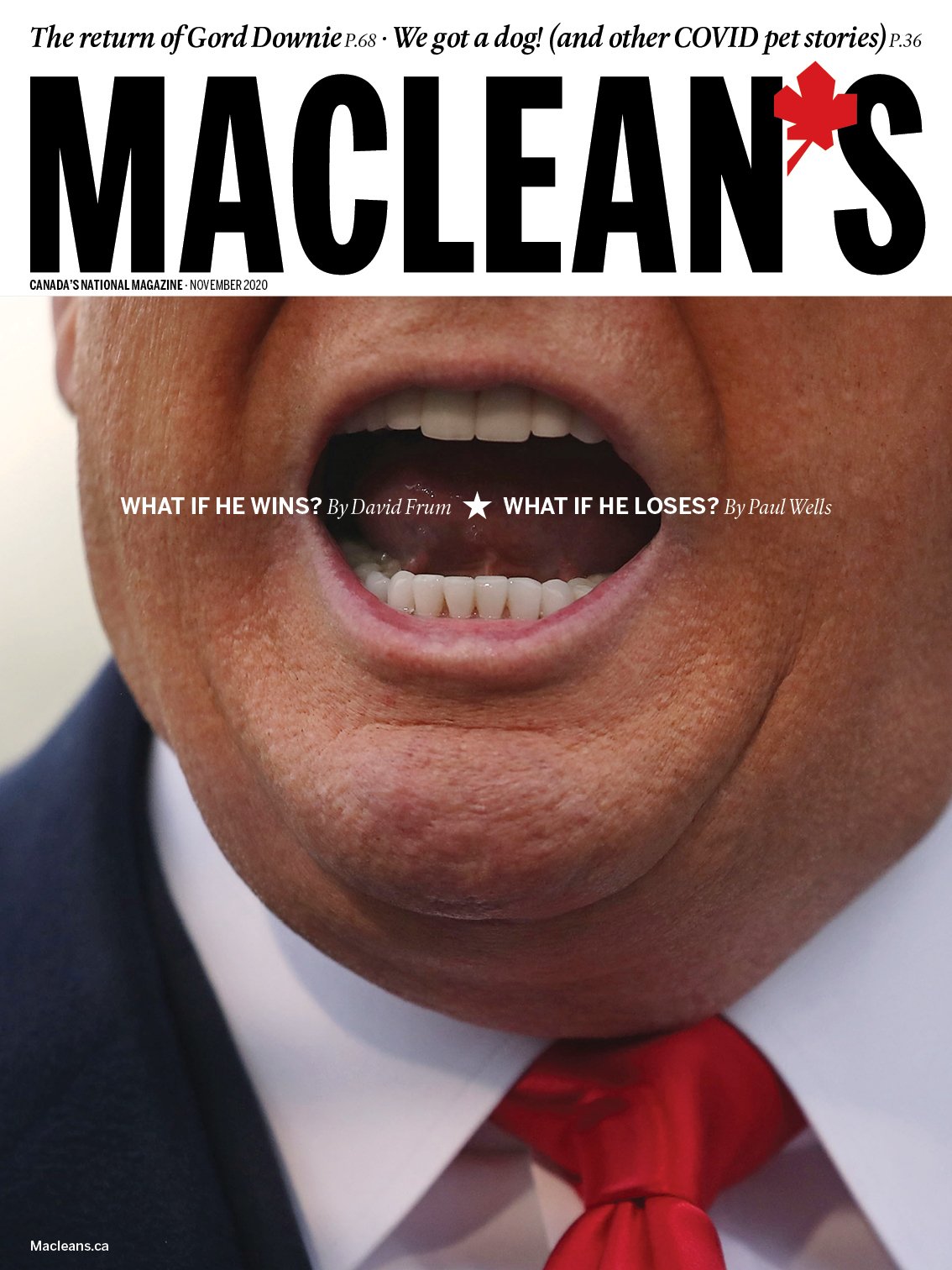

What if Donald Trump loses?

Paul Wells: The job of a president Joe Biden would be leading the cleanup crew after a vandal. At stake: the entire American project.

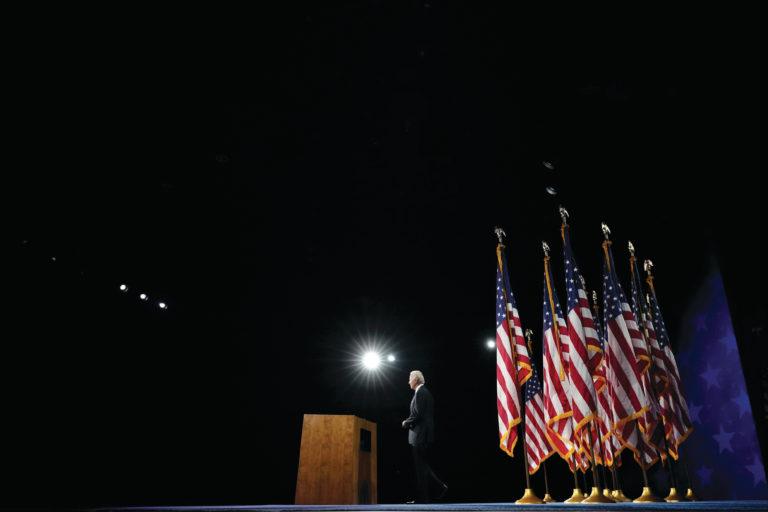

At 77, Biden’s fitness to govern will likely be doubted throughout his presidency if he wins (Andrew Harnik/AP/CP)

Share

Nov. 5, 2008 was a cloudy morning in Washington. A knot of reporters was watching outside the White House as President George W. Bush walked up to a podium facing them.

“Last night I had a warm conversation with president-elect Barack Obama,” he said. “I congratulated him and Senator Biden on their impressive victory. I told the president-elect he could count on complete co-operation from my administration as he makes the transition to the White House.”

Bush said he’d also called the defeated Republican John McCain to congratulate him on a “determined” campaign. But the 43rd American president made no particular effort to be even-handed as he contemplated the election of the 44th. For a generation who had lived through the civil-rights movement of the 1960s, Bush said, the election of a Black president was “a dream fulfilled.” When the Obama family walked into the White House, he said, “I know millions of Americans will be overcome with pride at this inspiring moment.”

DAVID FRUM: What if Donald Trump wins the 2020 U.S. election?

Eight years later, when it was Obama’s turn to comment on Donald Trump’s election, his own remarks were almost as gracious. “We actually have to remember that we’re all on one team,” Obama said. “We’re not Democrats first, we’re not Republicans first, we are Americans first.”

So maybe a defeated Donald Trump will embrace his fate with grace, sing odes to the democratic process, and order his staff to ensure Joe Biden’s presidency starts on the right foot.

It’s also increasingly likely the election won’t be decided on election night—that the leaden animosity and duelling lawsuits that took the Bush and Gore campaigns all the way to the Supreme Court a month after the 2000 election will look, in hindsight, like a walk through clover.

A president who’s already been impeached for using state powers to pursue partisan ends could do a lot more of that. A Supreme Court with three Trump-nominated justices could be called on to arbitrate the election result.

And, of course, things could get far worse. Maybe somebody will take seriously the words of Michael Caputo, the Trump campaign staffer who somehow managed to become assistant secretary for public affairs at Health and Human Services during a lethal pandemic. In September, Caputo told a Facebook Live chat that “there are hit squads being trained all over this country” to prevent a second Trump term. “You understand that they’re going to have to kill me. Unfortunately, I think that’s where this is going.”

Caputo took a leave of absence a few days later but, astonishingly, he still has his job. Politics has already come to bloodshed again and again in recent years. It’s not obvious why that would end, just because a president who repeatedly encourages violence wins even fewer votes in 2020 than he did in 2016. Trump himself is less than helpful on this score: he spent the last days of September spectacularly failing to answer repeated questions about whether he would respect the election results if Biden comes out on top.

If Trump does contest the election, what happens next becomes fundamentally unpredictable. It may well entail widespread violence, and I’m not going to spend a lot of time talking about it. Not because I want to deprive you of your pleasure as a reader of disaster fiction, but because I’m here on assignment, and my assignment is to consider a Biden presidency. So I’m just going to have to assume that at some point, somehow, a Biden presidency begins. And start there.

Purely in the spirit of this exercise, let’s assume a decisive Biden victory within a small number of days after Nov. 3. Let’s begin after a Trump concession speech. This scenario takes things for granted that cannot be taken for granted, but we have to start somewhere. And after all, removing Trump from the Oval Office hardly eliminates the challenges facing the new president.

A Biden presidency is fascinating to imagine, without regard to how we might get there from here, because it will test the ability of a man, the powers of his office and the resilience of his country.

RELATED: Donald Trump’s presidency: A shocking list of things he’s done

The man is really old and not conspicuously accomplished. Joe Biden will be the oldest president in the history of the republic, 78 years old on Inauguration Day, eight years older than Trump or Ronald Reagan. According to the United States Office of the Chief Actuary, a man Biden’s age has about a five per cent chance of dying within a year, rising to just over six per cent in the fourth year of his presidency. So statistically, the odds are roughly one in five that he’ll die and leave his vice president, Kamala Harris, to succeed him.

The likelihood that his fitness to govern will be doubted, including by some who voted for him, is higher, rising to near certainty, on every day of the next four years. The last couple of Democratic presidents came from the highest echelons of academic achievement: Bill Clinton was a Rhodes Scholar, Obama the first Black president of the Harvard Law Review. Biden graduated from the University of Delaware and Syracuse University’s law school.

The journalist Nicholas Lemann once identified three subspecies of the American leadership class: superbly educated Mandarins, who bring portable skills to a broad array of problems; unpredictable Talents, who come from outside a system to disrupt it and catch everyone off-guard; and Lifers, who start at the bottom and work their way up. Clinton and Obama were at least part Mandarin. Trump, God help us, is a Talent. Biden is a consummate Lifer. He ran for president, repeatedly, for the same reason Jean Chrétien wanted to be a Canadian prime minister: because it was the next thing to do. It’s not true Biden is devoid of reformist instinct: he was ahead of Obama on same-sex marriage. His $2-trillion climate plan, though largely a plan for union construction jobs, would probably end up doing more to reduce carbon emissions than anything the White House accomplished while Al Gore was in it. But it would be farcical to pretend Biden wants to besiege the American way of doing business the way Bernie Sanders or the new generation of radicals led by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the House of Representatives do. As the former Reagan speechwriter Peggy Noonan said in a mostly good-natured interview about Biden for the PBS documentary series Frontline, he is “a respecter of what is.”

Except that this year, of course, he’s been America’s leading respecter of what was, until just before Trump came along. His ambition this year is to lead a counter-reformation against the Trump revolution, or a cleanup crew in the wake of a vandal if you prefer. This makes him the enemy of Trump admirers, of course. It has also frequently frustrated Democrats whose ambitions are higher than resetting the clock to mid-2016.

If nothing else, trying to erase Trumpism will keep Biden busy. The Washington Post has tallied everything he’s promised to do on Day 1 of his presidency. It’s a long list. He’ll rejoin the World Health Organization. He’ll call NATO allies, “saying we’re back.” He’ll “end the Muslim ban” and “work with Congress to pass hate-crime legislation.” He’ll tighten gun laws, create a pathway to citizenship for 11 million undocumented immigrants, set about eliminating Trump’s 2017 tax cuts and give his housing secretary 100 days to end homelessness. He would reinstate transgender students’ access to bathrooms and locker rooms.

There are several more items on the Post’s list. All are at least rhetorically slated for Day 1; Day 2 already feels like a letdown. “We’re going to have to move on a whole hell of a lot of fronts,” Ted Kaufman, who served out Biden’s Senate term when he became vice president and is leading Biden’s transition team, told the Post.

He’ll already have built up a sense of momentum before his inauguration, as all presidents-elect do. Presidential transitions have a way of showing off the bench strength of the American civic and intellectual elite. Most new administrations dazzle with the array of fresh talent deployed to cabinet posts, senior staff positions and the top layers of the bureaucracy.

Beltway and media speculation suggests a Biden cabinet could include Elizabeth Warren—the Massachusetts senator whose detailed plans for taking the big banks down a notch fuelled her presidential campaign—as treasury secretary. For secretary of state, maybe Susan Rice, Obama’s first-term national security adviser. Or even Mitt Romney, his 2012 Republican opponent. The latter choice would leave Rice free to be White House chief of staff. Eric Garcetti, the mayor of Los Angeles, has been rumoured as the head of Housing and Urban Development. Biden could send Pete Buttigieg to the United Nations and put Washington state governor Jay Inslee, whose single-issue presidential campaign on climate policy everyone ignored, in charge of the Environmental Protection Agency. As the list of nominations grows through December and January, there would be a sense that competence was once again welcome in the Oval Office.

READ: Can Joe Biden win the presidency from his living room couch?

Biden has always depicted himself as a unifier, determined to rise above faction in a chronically polarized country. Making Kamala Harris, who did her best to hurt him in Democratic primary debates, his vice presidential running mate fits that brand. So would building a cabinet that reflects the various wings of a Democratic Party that’s increasingly estranged from itself. And he’s sure to find room for Republicans and Trump appointees, whether it’s elevating Romney or keeping Jerome Powell, who was named to the Fed board by Barack Obama and became Trump’s pick to become the central bank’s chair.

Simply by having a transition plan, Biden would mark a clean break from his predecessor. Michael Lewis’s book The Fifth Risk is largely about how Trump became the first modern president without a transition team worth the name. The U.S. bureaucracy is composed, to a much greater extent than Canada’s, of political appointees. The entire senior management echelon at highly technical government departments like Agriculture and Energy serves at the pleasure of the president. Every administration names up to 6,000 senior bureaucrats, very few with particularly partisan tasks. Beginning the day after an election, parking lots are held clear in dozens of government buildings, waiting for the new team to arrive for briefings. But after Trump was elected they never arrived.

After the inauguration, top-level managers began to arrive in dribs and drabs, Lewis writes, but “the people who showed up had no idea why they were there or what they were meant to do. Trump sent, among others, a long-haul truck driver, a telephone company clerk, a gas company meter reader, a country club cabana attendant, a Republican National Committee intern and the owner of a scented candle company. One of the CVs listed the new appointee’s only skill as ‘a pleasant demeanour.’ ”

A Biden presidency will mark a re-professionalization of the apparatus of the American state. People who know about product safety will be in charge of product safety. Diplomats will be ambassadors. Nuclear physicists will watch over nuclear power plants. Sometimes the most important changes are the least noticed.

But if a preference for competence as a hiring criterion were enough to fix all that ails America, then the Obama presidency would have rendered a Trump presidency impossible. America was already deeply challenged before Trump won Florida, and very few of the threats facing the country will go away even if Trump does.

It’s easier to know where to begin listing those threats than to know where to end. A still-virulent coronavirus pandemic will still be killing hundreds of Americans a day in January. Americans have turned the tools for fighting the plague, from face masks to an eventual vaccine, into the totems of partisan dispute, ensuring that many dozens of millions will endanger their lives and others’ to score political points. The nation’s industrial middle class is shattered. A rising and belligerent China will keep working to extend its advantage whether the U.S. pushes back or not. A global decline in democratic freedom has continued for a decade and a half. The post-war alliance system, led by NATO, was already wondering about American steadfastness and fitness to lead before Trump was elected. The summer brought the latest in a long series of reckonings with a legacy of racist violence dating back centuries. The endless epidemic of death by mass shooting will resume as soon as Americans can congregate in sufficient numbers to offer easy targets. The climate crisis is deepening. Public infrastructure is rotting.

The road to this crisis of American confidence was paved with previous presidents’ best intentions. Bill Clinton’s mid-1990s welfare reform probably aggravated extreme poverty. His decision to champion China’s admission to the World Trade Organization has resulted in China exporting despotism instead of importing democracy.

READ: Donald Trump proves narcissism is no cure for COVID-19

George W. Bush’s second inaugural address in 2005 called for freedom to spread around the world. The Washington-based Freedom House think tank marks that very year, 2005, as the beginning of a measurable and constant decline in global freedom. “Democracy and pluralism are under assault,” the group’s latest annual report says. It’s as though the Iraq invasion and the black-site torture rooms made a mockery of the values Bush hoped he was promoting.

Part of Barack Obama’s legacy is a racist backlash that began while he was still in office and accelerated under Trump’s gleeful stewardship, a backlash that echoes shameful episodes throughout American history. That part of Obama’s legacy is not his fault. There’s more room for debate about Obama’s role in sparking the populist movements that sprung up on the left and right—Occupy Wall Street, the Tea Party and their assorted successors—after the bank bailout of early 2009. Families trusted banks with their life’s savings and lost. The banks got government bailouts. The families were shattered.

To this day, Obama and his treasury secretary, Tim Geithner, will launch a spirited defence of what they did. But voters remember, and whatever he does, for as long as he’s president, Biden will face headwinds of disillusionment and disdain stirred up the last time he worked in the White House.

As he picks his path forward through the wreckage of earlier presidents’ legacies, Biden will be sabotaged by his immediate predecessor—and not always supported by his Democratic colleagues.

Donald Trump was just a reality-show host when he appointed himself the country’s chief promoter of fatuous and spurious attacks on the legitimacy of Obama’s presidency. He will be an ex-president, surely embittered, certainly with too much time on his hands, when he continues his Twitter campaign against Biden. It’ll hurt, partly because there will be many Republicans who view Trump as a model to emulate as they plot their own careers.

Polarized politics usually encourage political movements to rally, but there’s no guarantee Democrats will rally to Biden. Much of America’s progressive left views him as a dinosaur, an appeaser, a supporter of the Iraq war, an enabler of Obama’s weakest instincts in the fight for progress. Biden’s rise to the Democratic nomination embarrassed a lot of younger Democrats. They’ll be fair-weather friends at best, if even that.

Will his be a successful presidency? My God, I don’t know how anybody could pretend to be able to answer. It’ll be tough, that’s for sure. How it works out will depend on the president, his party, his nation and its friends. Every player in that drama will have their work cut out for them.

One of the most striking pieces of music I’ve heard this year is a new melody for Francis Scott Key’s poem The Star-Spangled Banner, written by composer Kile Smith for a Texas chamber choir called Conspirare. Smith wrote the piece in honour of Sarah Winnemucca Hopkins, a Paiute author from what is now Nevada, whose father knew Key’s poem and taught it to her.

“Of all the national anthems,” Smith writes, “The Star-Spangled Banner is the only one that’s a question. Is the flag still there? The flag we saw yesterday, before the night and the bombs fell on this land of the free and the brave, is it still there?” The American project is always provisional, never set. Conceived in liberty, that radiant and lurid nation has often been tested, often found wanting. The paths it finds through each new fiery trial are beyond any one woman or man’s ability to wreck or redeem. But is the quest still worth it? Is the flag still there? Maybe. That’s the hope that will guide Joe Biden, if he gets his chance.

This article appears in print in the December 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “What if Trump loses?” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.