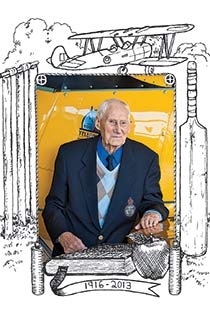

Archie Munro Pennie

A natural pilot, he was as passionate about aviation as he was about punctuality. His latest project was restoring antique clocks.

Illustration by Team Macho

Share

Archie Munro Pennie was born prematurely on June 16, 1916, in Banff, Scotland, and spent his first month in a shoebox next to the family stove. His mother, Margaret, was a nurse, while his father, Alexander, was a tailor who claimed he introduced the zipper to Scotland. At age six, Archie lost his father—likely to tuberculosis—and younger brother, George, to meningitis. His mom moved with Archie and his older brother, Jimmy, to live with their uncle in Elgin, Scotland.

Archie was a mischievous child, full of energy. Some evenings, he and a friend would stand on either side of the road, each holding the end of a piece of string to knock off the hats of men walking by.

Archie went to school at Elgin Academy, where he played cricket and—after a match against the private school Gordonstoun—bragged about catching out Prince Philip. Archie later studied explosives at Glasgow University and found a job as a chemical engineer with the Woolwich Royal Arsenal.

He first came to Canada in 1942 to learn to fly with the Royal Air Force at its wartime training school in Assiniboia, Sask. Archie picked up flying so quickly, he was asked to stay and teach. From the back seat of a Stearman—a biplane without a canopy—he boasted he could tell by looking at the backs of the ears of his students whether they were about to be sick. Never one to waste time, Archie would invert the plane for the student to throw up, then right the plane and continue with the lesson.

Archie went back to Europe at the end of the Second World War and achieved the rank of flight lieutenant.

He returned to Woolwich before getting a job with Canada’s Defence Research Board in Quebec City in 1948. On a transatlantic boat ride to the U.K. in September 1949, Archie met Barbara Smith, who was visiting Europe with her father—then owner of the Ottawa Journal—E. Norman Smith. Barbara felt unwell aboard, so Archie stepped away from the bar to introduce himself, and said her seasickness was all in her head.

After a first date at the Cumberland Hotel in London, Barbara left to tour Europe. Archie wrote to her every day. She fell for Archie, who didn’t act like the stuffy Ottawa crowd she was accustomed to. Once Archie returned to Quebec, he took the train twice to visit Barbara in Ottawa. After only three dates, they were married on June 24, 1950.

While living in Quebec City in 1952, the couple’s first child, Ross, was born. Three years later, after Archie’s work took the family to Fort Churchill, Man., they had a daughter, Sheena. The family ended up in Suffield, Alta., in 1957, where Archie worked for the Defence Research Board as the station’s chief superintendent. In a small town consisting only of government employees, “he became the de facto mayor,” Ross says.

Archie stopped flying after the war, but kept his love of planes. “His whole reason for being—if you can pick one thing—was learning to fly,” Ross says. “The combination of science, movement, speed and freedom is what he loved.” In his spare time, Archie loved to build things from spare parts, such as a go-kart with a washing-machine engine. “He was happiest in his workshop—no question,” Ross says.

He was an intellectual father, waking up his children by quoting the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, but was sometimes short on patience. If the family was meant to be out the door at 6 o’clock, he expected everyone to be ready at 5:45. Archie got up every day at 6:45 a.m. and went to bed every night at 9:30 with an apple and a book.

In 1964, the family moved to Ottawa and, when Archie retired at 59, he became a clockmaker. He restored antique clocks, built two grandfather clocks and joined a clock enthusiasts’ club. “We must have had 50 pendulum-swinging, clinging, clanging clocks,” Sheena says. “You wouldn’t want to be there at noon or at midnight.” In his late 80s, Archie’s eyesight started to fail, so he started taking the bus to the library to pick up books on tape. “He still had a mind like a steel trap,” Ross says.

On Aug. 25, as he would do every week, Archie went to wind the grandfather clock in their apartment. The clock toppled onto him. He got up and went to get a haircut. After returning from the barber, he lay down in bed and became breathless. Six of his ribs were fractured. After three days in the Ottawa Civic hospital, Archie’s lungs stopped working properly and he died of respiratory failure. He was 97.