Behind the evolution of Montreal’s Biodôme

The animals that inhabit Montreal’s beloved Biodôme are at the centre of its recent overhaul

(Photograph by Claude Lafond)

Share

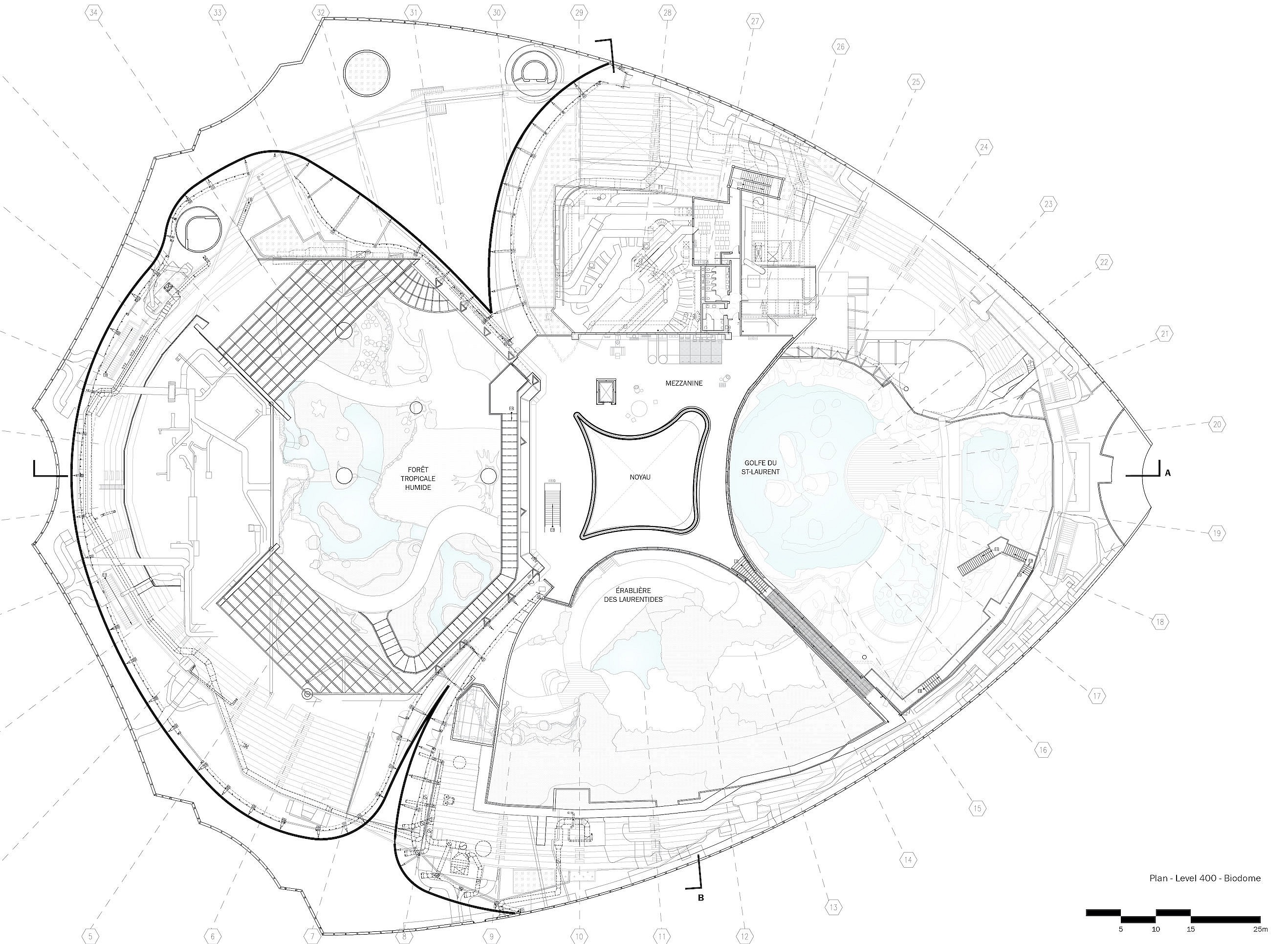

Julie Jodoin is fine with most descriptions of Montreal’s Biodôme—just not zoo. “At a zoo, you observe animals,” says Jodoin, acting director of Space for Life, the city-owned organization that operates the popular museum. “Here, you’re immersed in their world.” Since its opening in 1992, the Biodôme has housed 200-plus species in five reproduced ecosystems beneath the soaring concrete vault of the city’s Olympic velodrome. Live lynxes prowl the perimeter of its Laurentian Maple Forest, while the Tropical Rainforest area comes complete with outfit-soaking mists.

By 2014, however, Space for Life’s leadership felt that the Biodôme wasn’t immersive enough. That year, the museum launched an international design competition, with the goal of adjusting the building’s rote, linear traffic flow and expanding visitors’ exposure to the animals. The winner was Kanva, a small Montreal architecture outfit whose proposal was designed in collaboration with Montreal’s Neuf Architectes and the engineering firms Bouthillette Parizeau and NCK. Kanva’s co-founder, Rami Bebawi, had a flash of self-doubt after his victory. “I knew how to design for people,” he says. “Not penguins.”

After a two-year renovation—and plenty of collaboration with local biologists—the Biodôme reopened in August of 2020, greeting museumgoers with an eye-popping new feature: its grand entrance hall is now enveloped in a “living skin” made of four-storey swathes of polyester coated with PVC. At the back of the hall, the skin narrows to a slender passageway whose floor slopes almost imperceptibly upward, slowing visitors to prepare them for the wilderness within.

The ecosystems got a makeover, too: Kanva chose finishes like glass and local ash wood, materials that are more resistant to decay. The team also designed the museum’s new matrix of ramps to properly shade the Biodôme’s many plant species and shifted its existing rock formations to facilitate more aerodynamic penguin belly flops. Elsewhere, a basin full of fish, previously obscured by rocks, has been raised, allowing visitors to get closer to the Biodôme’s cast of creatures than ever before. “The whole idea of the redesign is that these animals are not exhibits,” Bebawi says. “This is where they live, and we are their guests.”

THE VELODROME

Kanva’s renovation is also a restoration of an Olympic landmark. Designed by French architect Roger Taillibert, the facility’s original architecture—and, in particular, its vast, vaulted ceiling—was largely obscured in the Biodôme’s previous incarnation.

THE LIVING SKIN

The skin’s seemingly endless surface is multi-functional: it muffles sound and acts as a demarcation between the museum’s entrance and its ecosystems. The material is resilient enough to handle outdoor exposure—necessary, given that it adjoins five dramatically different climate zones.

THE MEZZANINE

This area offers an aerial perspective of the Tropical Rainforest, Laurentian Maple Forest and Gulf of St. Lawrence ecosystems. It also contains the Bio-Machine, an interactive exhibition where visitors assume the role of ecosystem “operator,” toggling the environmental factors that keep the various biomes in balance.

THE ICE TUNNEL

The entrance to the Sub-Antarctic Islands ecosystem is a downward-sloping passage encrusted with ice. Its frosty walls are 20 centimetres thick.

This article appears in print in the August 2022 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here, or buy the issue online here.