Beloved editor, writer Bob Levin: ‘The real deal’

He spent four decades fighting cancers but never lost his determination to live life on his own terms.

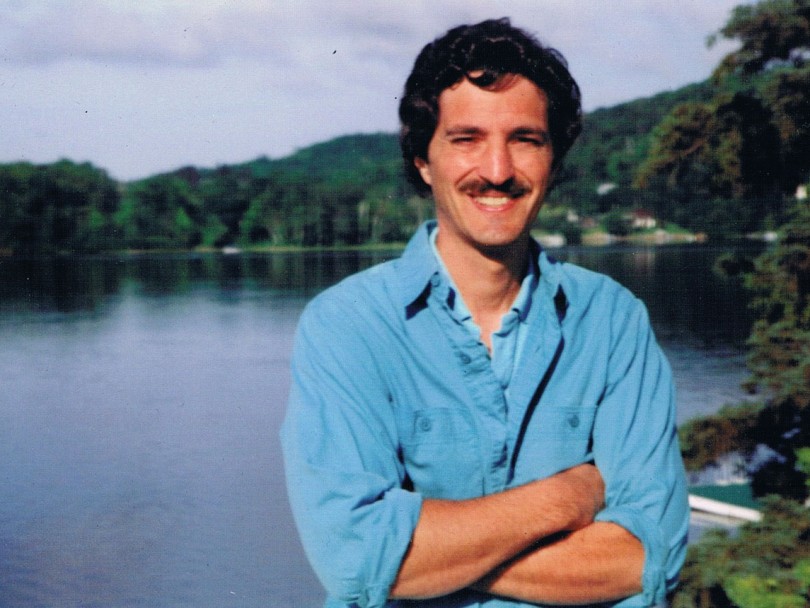

Bob Levin.

Share

At one point in the quietly magical 2016 novel Away Game, the father of the protagonist laments: “You learn early on, things rarely work out the way you want.” The author, Bob Levin—long-time Maclean’s writer and senior editor (who later spent a lengthy stretch at the Globe and Mail) wrote from personal experience. A restless, energetic youth in his native Philadelphia, Bob was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at age 18. By the time of his death of related causes, on Jan. 29 at age 66, he had spent more than four decades fighting cancers that ravaged his body but never diminished his determination to live life on his own terms.

Bob is recognized by fellow journalists as one of the country’s most gifted writers and editors—a master craftsman who could whip out a brilliant essay in hours, or turn someone else’s unreadable dreck into a polished piece in even less time. He came to Maclean’s and Canada in the mid-1980s, initially uncertain how long he would stay. He quickly learned more about his adopted country than most people born here, travelling its length and breadth, soaking up information and experiences, and recounting them in a knowing, affectionate way. As an executive editor—I know this first-hand from my 2001-05 time as Maclean’s editor-in-chief—not a word of the magazine went out without his scrutiny. That applied to other editors as well: as my predecessor Bob Lewis recalls, “You always felt better when Bob Levin handled your piece.”

In the best of ways, Bob was often a royal pain to the editors above him in the pecking order. If he disagreed with a story’s treatment, he would hover outside the office, pacing until he got a chance to make his point. He never minced words, and often won. He was as patient with writers as he was impatient on those occasions. Maclean’s present Ottawa bureau chief John Geddes recalls: “Talking about a story with Bob, or an issue of Maclean’s, or for that matter a paragraph, a sentence, or a word, always made me feel I was in company of the real deal.”

That said, Bob could, on occasion, be succinctly scathing when he saw prose he didn’t like. Maclean’s managing editor Charlie Gillis recalls that after he once submitted some rather convoluted “word salad,” Levin sent it back with a one-word note: “Huh?” Like all wordsmiths, he could be idiosyncratic: his loathing of the construction term “hoardings” was legendary among the magazine’s fact-checkers. He was just as baffled about the popularity of curling, which he insisted was not a true sport like his beloved baseball.

As a writer, Bob was a master at essays that captured, in crisp clear prose, the emotions surrounding an event. When Canada and the United States played each other for the gold medal in women’s hockey at the 2002 Winter Olympics, he discovered which side was now his favourite. “The truth was this,” he wrote, “I’ve become Canadian.” But he could not help but close with a gentle gibe, observing that the U.S. “won twice as many medals as Canadians.” One year earlier, days after the stunned horror that greeted the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States, he limned the feeling of so many people toward “a small world getting smaller; nearly everyone knows someone, or at least someone who knew someone—so few degrees of separation.”

His writing reached hundreds of thousands of readers. But for the fortunate people who knew him first-hand, Bob’s personality shone most brightly. He loved his family—fellow journalist Nancy White, son Matt, and rescue dog Can. (Bob bristled when people talked of his “courage” in fighting cancer: as he often observed to his close friend James Deacon, Nancy was the rock from which he drew his will to keep going.) He also loved baseball (his boyhood team, the Philadelphia Phillies, and his adopted Toronto Blue Jays); summer getaways to Muskoka; good prose; his colleagues and friends (mostly interchangeable); music; lively conversations and a good joke. He seldom sought the spotlight, but didn’t duck it if the occasion was right. More than 30 years after the fact, a cherished memory of long-time friend and colleague Bruce Wallace is of Bob singing the ’60s classic “Up on the Roof”—loudly—in a Calgary bar during the 1988 Winter Olympics. (Related side note: Bob did not drink.)

With his wiry build, neat mustache, and “uniform” of black turtleneck under collared, usually flannel, shirts, Bob seemed unchanging despite the toll exacted by his bouts of cancer and its repeated, draining treatments. His will was so strong that it was almost possible to ignore the way cancer kept attacking him—three times for Hodgkin’s and then, in 2016, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma—and how much more physically diminished he became each time. Radiation and chemotherapy took away his hair several times; he called it a good excuse to wear his baseball cap in the office. The illness and treatments, including a stem-cell transplant, devastated his insides, taking away his ability to eat almost any kind of food and playing havoc on his immune system. (He wrote moving essays in the Globe describing his mindset each time treatments began, and the foods he remembered so fondly that he could never eat again.) In recent years, he was largely confined to either a hospital room or his house, unable to venture far because of his weakened immune system and overall state. But through emails, social media and occasional phone calls, he remained very engaged with the outside world and his many, many, many friends.

In 2016, Bob achieved a lifelong dream with the publication of Away Game, a mystical work that centred on baseball, coupled with time travel, and a son’s complicated relationship with his father. What mattered most were the gentle, thoughtful meditations on the passage and meaning of life, wrapped neatly inside an engaging plot. At the time of his death, Bob was reading the proofs of his next book, Theater near You, which features a narrator battling recurrent cancer.

Writing sustained Bob as his physical world continued to shrink. “My ability to travel right now is extremely limited,” he wrote in one of our email exchanges last year. “I guess my substitute remains writing.” In that way, he transcended his physical limitations to reach out and touch—and be touched by —a world he never ceased to appreciate. In that way, Bob won his decades-long battle with cancer: he never allowed it to define him or take away from his appreciation of the people and world around him.