My life in a tiny-home community

“A Better Tent City empowers its residents by offering them privacy, independence and stability within the safety of their own home”

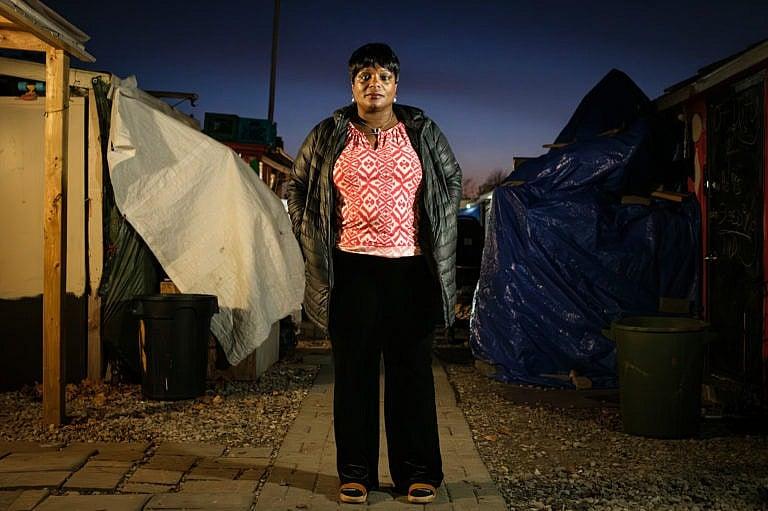

KITCHENER, ONT.: NOV 12, 2023— Nadine Green is photographed next to her tiny home at the Better Tent City community in Kitchener, Ontario, on Sunday November 12, 2023. Green is the site coordinator and her job requires her to live in one of the tiny homes. A Better Tent City is one way people in Kitchener are addressing the homelessness crisis, through tiny homes or cabins and a central dining/washing facility on undeveloped land. (Giovanni Capriotti)

Share

I live in an eight-by-10-foot house at A Better Tent City Waterloo Region, a community of tiny homes in Kitchener, Ontario. I’m the site coordinator, which means I’m responsible for the well-being of the community—I work, and live, alongside the residents. My duties include daily check-ins with residents, connecting them with supports, mediating disputes, fostering partnerships and any other tasks that pop up. I’ve been living and working here since the community was founded in 2020, and I plan to live here for as long as it takes for residents to find permanent housing.

I sleep soundly, unbothered by the speeding cars that whirl down Highway 7. The lock on my door is one of my tiny luxuries. When I wake up, the smell of coffee and freshly cooked bacon from the nearby common space waft through the air. I open my eyes to the smallest amount of light peeking through my small window, and immediate gratitude washes over me.

I moved from Jamaica to Canada nearly 40 years ago, when I was 16. My parents divorced, and I had to go with my mother and her new husband to Cambridge, Ontario, leaving my father behind. I didn’t want to leave my home, the salty air and the year-round sun,

READ: Why an Ontario city is now permitting homeless encampments and tiny homes in parks

I moved out of my family’s house in high school; I didn’t want to be on my own, but families can be complicated when you’re only 16. I spent my later teen years hiding that I was homeless. I went to school and played sports, and then at night I would search for unlocked apartment lobbies that I could sleep in.

I had heard that Kitchener was a better place than Cambridge for unhoused people. There were more shelters and community services for those experiencing homelessness. So, after high school, I made my way to Kitchener. That’s where I met Jerry—the first and maybe the only person I would ever love. We welcomed a son in 1989, while living at a rooming house; he had non-verbal autism. I worked at Arby’s, and I often brought food home for my neighbours, who were struggling. But Jerry’s mental health deteriorated, and our relationship ended. After 15 long years of being a single mother with no support, I was eventually able to secure a spot for my son in an assisted-living facility.

By 2004, I had opened my own convenience store in downtown Kitchener. My goal was to treat all of my customers with kindness and love regardless of their situation—so much so that I allowed unhoused people to start sleeping in my store at night. Kitchener’s shelter system is often unwelcoming, so I helped those who were forgotten about. It started with just a few people. I would stay open late and let them sleep in the aisles if it were cold or rainy outside. I would let them take whatever they needed from the store and write it down on a tab, unbothered by when, or if, they could pay me. I offered free apples and bread to anyone who needed it. Word got around that I was offering a warm, dry place to sleep, and more people came.

In 2012, I was evicted from my store for allowing unhoused people to take shelter in it overnight. So I found a new one on Water Street North in downtown Kitchener. Again, I allowed people experiencing homelessness to sleep in my store. I even got rid of my apartment and built a bed in the back office of the store so I could supervise the scene and make sure I could always be open if someone needed shelter.

A few years later, things were getting tough at the corner store. A trendy new restaurant was set to open across the street, and my landlords weren’t happy that I was using a commercial property as a makeshift shelter. I was naive to think we’d all blend in together and that everyone would see the good in what I was doing.

I wasn’t popular among my neighbours and so, in 2019, when I heard some rich guy was looking for me, I thought it was someone who wanted to get me in trouble. But when he finally tracked me down, he said his name was Ron Doyle and he owned a massive convention centre in Kitchener called LOT42. Ron had lots of business ventures, including Hacienda Sarria, a popular wedding venue in Kitchener-Waterloo. He’d read an article about my prior eviction and had heard about what I was doing from friends he had downtown. Lots of people were talking about me and my store—not always in a good way. But Ron was interested, and he started bringing his important friends to my store to show them my solution to the housing crisis. He introduced me to his friend Jeff Wilmer, who was the former director of planning for the city of Kitchener and later chief administrator for the city. He was passionate about helping unhoused people. I didn’t know why Ron took such a liking to me, but we quickly became friends.

By then, the store had become a full-on shelter. The paying customers stopped coming and the shelves were basically bare. But Ron’s support gave me hope. I finally felt like I had someone on my side. Then my landlords took me to court. After a complicated legal battle, I was evicted and told I owed two months of rent, which I didn’t have. Ron ended up writing me a cheque for $2,800 like it was the easiest thing in the world. I accepted, although taking money from him made me uncomfortable.

While I looked for a new storefront, I lived out of my car and drove around Kitchener delivering meals to my community. I tried to take my store mobile—I called the project Going Mobile KW—and invested all my time in my new project. But I felt a weight: I wasn’t helping Kitchener’s homeless like I once had.

For the first time in a long time, I cried—and once I started, I couldn’t stop. I sat in my car and cried as the sun began to set, as day turned into night, as unhoused people searched for a safe and warm place to sleep, dispersed yet again. My heart hurt for them; it was one of the first times I didn’t know how to help. But then, like a sign from God, my phone rang. It was Ron.

He asked me to get lunch with him and Jeff. Knowing Ron, I figured he had something up his sleeve. When I showed up the next day, the two of them were sitting at the table with notebooks and binders. They explained to me their idea for A Better Tent City—a community of tents and tiny homes on Ron’s LOT42 property. The site had been—in Ron’s words—a failed attempt at a convention centre. It was a huge property that often sat empty, so he told me to bring people there and he’d open his doors to anyone who needed shelter. For the first time in a long time, I had hope.

I drove around looking for the people who used to sleep in my store. One by one, I picked up anyone who wanted to come and took them to LOT42. I was the first official resident and volunteer, but I was also responsible for getting the word out.

It was early 2020, and COVID-19 was sweeping across Canada. While everyone was told to stay inside and isolate, starting in April, I collected unhoused people and brought them to LOT42. There were washrooms and shelter. I only brought 10 or 15 people—all of whom who used to sleep in my store. Even Alvin, my old part-time employee, was there. It was like a reunion. We all knew each other and we had all slept under the same roof before. After months of being dispersed, it felt good to be together again. People slept in tents and on the floors of the convention centre. It wasn’t ideal, but it was better than sleeping outside.

Slowly, A Better Tent City turned into something more. Through a partnership with the Social Development Centre Waterloo Region, we were able to bring in 12 cabins with insulation and beds at a cost of approximately $35,000. The shower and laundry facility that followed cost about $30,000 to install.

READ: This Ontario hospital network is prescribing housing to patients—and building homes on its property

Soon, instead of living communally and sleeping on the floors of the convention centre, my friends had their own small cabins where they could store their belongings safely. They could sleep soundly at night without fear. They could live with their partners and keep pets and seek solitude when they needed to. They had their own homes within a friendly and safe community. I did too.

But in the midst of all this good, Ron was dying. He started coughing a lot, and he’d jokingly say that he only had a few more months to live, but I was never sure if he was kidding or not. He still showed up every day to make sure everyone was okay. Even when he was hospitalized, I would call him to report the “LOT42 Dailies,” a collection of stories from A Better Tent City that would have Ron roaring, and coughing, with laughter.

The last time I spoke to Ron, he called me for the Dailies. I re-enacted a silly argument some of our long-time residents had gotten into, an argument I had settled. Ron couldn’t stop coughing and laughing. I promised I’d come see him in a few days, but he passed away before I could visit. He died of cancer in March of 2021 at the age of 69. After Ron’s death, LOT42 was sold. I knew that this wasn’t going to be the end of A Better Tent City. We had worked too hard. Our community was full of hope and love; it meant too much to too many people.

Little did we know that while Ron was alive, he was creating a plan for what would happen to us in the event of his death. We eventually were allowed to move to 49 Ardelt Ave—a 3,500 square metre grassy area between Ardelt Avenue and the Conestoga Parkway just a short walk away from LOT42. The space was granted by the City of Kitchener and the Waterloo Region District School Board, which each own a portion of the site. A forklift scooped up all the homes and moved them to a new location.

This is where we are today. We currently have 42 homes and 50 residents. Our land-use agreement was just extended to 2025. We are stable here. We are home.

My house is the first house of the 42. It’s canary yellow with a picnic table out front. My porch is covered in plants. Beside my front door is a plaque that reads: “This home was the last one donated by Ron Doyle, co-founder of A Better Tent City. It is dedicated to his memory.”

Inside my home is a comfortable bed that was donated by a lovely woman with a big heart. My TV, a gift from Ron, hangs on the wall. I have a chest that I painted orange, plus a couch, a microwave and a bookshelf. On my wall hangs a painting of St. Moses the Black—a gift from Father Toby, my priest at St. Mary Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows Roman Catholic Church and a volunteer at A Better Tent City. All the residents at A Better Tent City have homes that reflect who they are and what’s important to them, just as my house reflects who I am.

Behind my home are three connected portables, known as our common space. Inside, there is a large kitchen that is always full of volunteers cooking delicious hot meals for our residents. The middle portable has couches and tables, and then the last one has washers and dryers. The portables are open to anyone—not just residents. It’s a community space where friends can come together. It’s here that I often see Rick, one of A Better Tent City’s first residents and a good friend of Ron’s. Rick recently got an apartment, but he still comes back to A Better Tent City almost daily to volunteer, eat and visit his friends.

To the right of my home is the shower and washroom facility. In the mornings, I put on my robe, gather my caddy and walk just a few steps to take a hot shower. The individual cabins do not have plumbing, but the the washroom facility and common space do. These facilities are open to everyone; a hot shower is not something we take for granted.

Here, we aren’t tenting. We are doing better than that. Our homes are heated and cooled. Our water is hot. Our washrooms are sanitary. We are permitted as a public service/public use because the municipality is our partner.

READ: Why a housing-first model is the only way to solve the homelessness crisis

Like all communities, we have our issues. Residents argue, people have disrespectful visitors and folks manage mental health and addiction struggles. But here, they aren’t alone. As a site coordinator, I pride myself in my quick ability to resolve resident conflict. Our site superintendent, Brad, extends a helping, empathetic hand to anyone in need. The Sanguen Mobile Health Clinic visits us to offer addiction support. Board member Laura Hamilton works diligently with the Food Bank of Waterloo Region to deliver and organize food. The Working Centre helps residents access mental health services. Father Toby offers spiritual guidance. Here, we congregate and work to solve the problems that cause homelessness. A Better Tent City empowers its residents by offering them privacy, independence and stability within the safety of their own home. This kind of solution works—I’ve known it all along. We may not fit into the box that society wants to keep us in, but people like us have always, and will always, exist.

I still think of Ron every day. I talk to him when I’m in my house. I ask him for guidance as I carry out his vision for a better solution to homelessness. I also think of Jerry, who passed away in 2021 after a long battle with mental illness and addiction. He’s the person who took me in and loved me when I was first living on the streets, the person who gave me my beautiful son, who’s now 34 and towers over me.

Ron used to always reference the song “Anthem” by Leonard Cohen. He’d put his own spin on the lyrics. He’d say: “If you open your mind, just enough to let the light come in, there’s a crack in the system. If the people who are running our society would let a little light in, we can fix everybody’s problem.” We are the light. And we shine brighter when we are together as a community. One love.

—As told to Beth Bowles