The truth about concussions

From the archives: Eric Lindros and other pro hockey players on their depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts

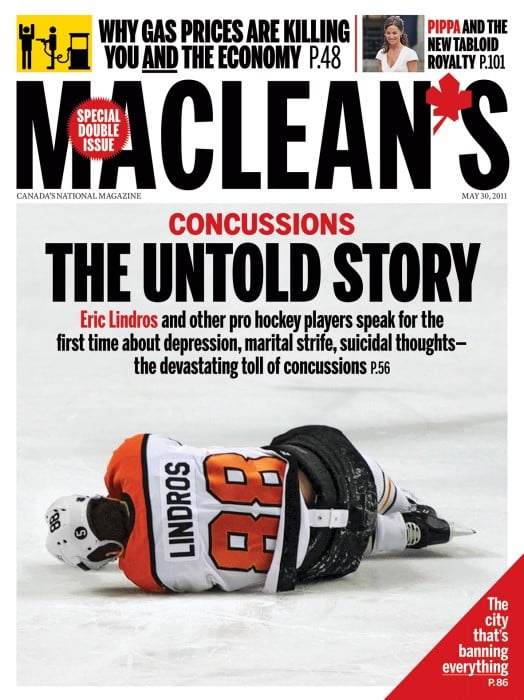

Photograph by George Widman/AP

Share

Today at Western University, NHL star Eric Lindros was scheduled to join medical experts at a symposium on sports-related concussion. Maclean’s examined the hidden toll of concussions in the pro hockey world in this cover story, published online May 19, 2011:

Before there was Sidney Crosby, there was Eric Lindros. Both were hockey prodigies as young teenagers. Both were drafted first overall into the NHL. Both won the league MVP in their early 20s, both were captain of Team Canada at the Olympics, and both were hailed as the next Wayne Gretzky or Mario Lemieux. And then, in a fraction of a second, both fell victim to devastating concussions. The toll on Crosby, who has been sidelined since January, remains to be seen. But most fans know that Lindros was never the same after a series of blows to the head—at least eight by the time he retired in 2007. What few know, however—what he’s never talked about publicly before—is the psychological and emotional toll of those concussions.

That a Herculean hockey legend such as Lindros (he is six foot four and 255 lb.) is speaking out with disarming candour about the panic and desolation that he has endured is unprecedented. “You’re in a pretty rough-and-tumble environment with this sport. Talking about these things—you don’t talk about these things,” says Lindros. So while he was playing in the NHL, Lindros mostly kept his game face on. “You got to understand, you want to wake up in the morning and you want to look at yourself and say, ‘I’ve got the perfect engine to accomplish what I need to in this game tonight.’ You are not going to look in the mirror and say, ‘Boy, I’m depressed.’ ”

But there were signs that the concussions had transformed him, both as a man and a hockey player, for the worse. “I was extremely sarcastic. I was real short. I didn’t have patience for people,” says Lindros, 38. That rudeness mutated once he stepped on the ice into fear that the next concussion was just one hit away. “That’s why I played wing my last few years,” he explains of changing positions late in his career. “I hated cutting through the middle. I was avoiding parting the Red Sea.” Off the ice, Lindros developed a paralyzing sense of dread at the very thought of public speaking or of being in a crowd—once routine activities for the sports superstar. “I hated, absolutely hated, that. I’d avoid those scenarios. I didn’t like airports. I didn’t like galas. It would stress me out.”

Although he didn’t realize it at the time, Lindros now believes there is one explanation for the downslide: the concussions. “The anxiety started in the late 1990s, in the midst of them all. I never had it before,” Lindros says. And he thinks that “there’s a real strong correlation.” Even after he quit playing pro hockey and the physical symptoms of concussion (headaches, fatigue) were gone, the anxiety persisted. His weight ballooned; he gained 30 lb. He also realized that the “great deal of frustration” he felt about the politics of hockey was depressing him as well.

Over the years, Lindros tried different treatments, including psychotherapy, to overcome post-concussion syndrome, the term for long-lasting symptoms. That’s helped a lot, he says, but the anxiety has been hard to shake: “It wasn’t until this year that I said, ‘Screw it, I’m going to get back into this,’ and I started doing career-day talks at high schools” and participating in public events. He has not made this progress alone, though. Along with the support of friends and family, he has a mental health professional to lean on. “I have someone I can call, and I can pop over and see,” Lindros says, “And I do from time to time.”

Since Lindros sustained that first concussion, awareness about the injury’s severity and complexity has improved, says Ruben Echemendia, a neuropsychologist and chair of the concussion working group for the NHL and the NHL Players’ Association: “We’ve gone from viewing this injury as laughable, a joke, to something people are recognizing can have serious consequences.” Part of that shift has come from seeing how concussions decimated the physical performance of players like Lindros. That he’s now opening up about how the injury wreaked havoc on his mental and emotional state is a breakthrough. “When people start to recognize that their idols have really struggled because of concussive injuries,” says Echemendia, “it starts to wake them up and move them away from the athletic culture of needing to be Superman.”

For whatever headway has been made, far too often concussion is downplayed by athletes and sports leagues, ignored by the public, misdiagnosed by trainers and doctors, and under-studied or not well understood by scientists. The same truths apply to mental illness such as depression and anxiety. Combine concussion and mental illness, and you have a truly perplexing situation: “We know that concussions are under-reported, some people say by a factor of three, others by a factor of 10. So I’m sure the effects of depression are also under-reported,” says Michael Czarnota, a neuropsychologist who works with the Professional Hockey Players’ Association, which includes many of the leagues that feed the NHL. “There is a stigma for people to come forward with these problems.”

Until now. Several former pro hockey players are breaking the silence, revealing to Maclean’s for the first time the anxiety, depression, isolation, broken relationships, loss of identity and even suicidal thoughts they experienced—and how they finally found a long road back to health. Lindros is first among them: “If no one says anything then it’s the status quo. The status quo is not working,” he says. “What most people don’t get is that underneath all the gear and styles of play, there’s a person. There’s a human being with feelings.”

It was Eric Lindros who gave former NHL player Jeff Beukeboom encouragement after his career-ending concussion in 1999. For two years, the hard-hitting defenceman couldn’t escape the pulsating headaches and a debilitating sensitivity to light and noise. “A real crowded area would knock the crap out of me,” recalls the four-time Stanley Cup winner. Worst of all was the relentless exhaustion, which compromised his ability to be a husband and father to his three children. “I couldn’t go out and play or do things with the kids physically,” says Beukeboom, 46, who had several previous concussions. Instead, he related to his toddler another way: “Me and him were on the same sleep schedule.”

No matter how much time passed, the symptoms didn’t lessen. “There was no alleviation. You get to the point where you say, ‘Oh God, here’s another day of feeling the same way. I can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel,’ ” Beukeboom recalls thinking. Eventually, after talking to Lindros about his struggle and using a combination of psychotherapy, antidepressants and active release treatment (muscle manipulation), he began to feel better. But the mental turmoil wasn’t easily shed. “After the recovery it was, ‘What now?’ ” says Beukeboom, who is the assistant coach of the Sudbury Wolves in the Ontario Hockey League. Back then, having played hockey for a living for 14 years, a different life was hard to imagine.

Kevin Kaminski had played four seasons in the NHL as a gritty centre when, on his 30th birthday in 1999, he also had to think hard about life after multiple concussions. “The doctor sat me down and said, ‘Look it, one more blow to the head, you might be killed or you might not remember your family,’ ” recalls Kaminski, now 42. “I was numb. I couldn’t believe it. Yet I guess I maybe knew in the back of my mind this could be it. When you have daughters, you want to be there for them.”

Kaminski was there for them and his wife, but only in the sense that he wasn’t on the road. “I isolated myself from my family,” he says, by shutting himself “in a dark room” to cope with the headaches and fatigue, as well as light and noise sensitivity. However much they offered support, patience and care to him, Kaminski couldn’t reciprocate. His moods swung from detached to enraged. Even Kaminski’s neuropsychologist had trouble getting him to work through the emotions. “He wanted to talk about how I felt, but I was just blah,” says Kaminski. So they’d resort to memory exercises, which agitated Kaminski because he couldn’t repeat back a list of four or five words. After grocery shopping, he couldn’t find his parked car. “My mind,” he says, “was just a mess.”

In time, and using antidepressants, Kaminski’s symptoms faded. But the injury had scarred him and his marriage. Last October, he and his wife finally divorced. “She said I wasn’t the same person anymore,” he explains. “And I don’t think I am. I don’t think I am.” Kaminski, who is now head coach of the Louisiana IceGators in the Southern Professional Hockey League, believes he knows what shattered his family. “I think a big part of it was the concussions,” he says.

The one solace Kaminski, as well as Lindros and Beukeboom, have had was the satisfaction that they had achieved their lifelong dream of playing in the NHL. For those pros who received their career-enders while toiling just one league down, the concussions have been all the more devastating. “Playing hockey my entire life, and hoping and planning for that to be my career—I was making all the right steps and working my way up to where I wanted to be,” says Rob Drummond, 25, who is still symptomatic two years after getting a career-ending concussion while playing right wing in the American Hockey League. “That’s been the most difficult thing, trying to find a different area to pursue. For me, nothing will ever really compare to playing in the NHL.” For now, he’s getting his business diploma and coaching youth hockey in London, Ont.

Still, Drummond has a few things in common with Kaminski. “I had one relationship that didn’t work out. I partly blame the concussion because it changed the person I was,” he says. “I went from being a person who enjoyed being around people to someone who just wanted to be alone and didn’t want to communicate.” It’s not that Drummond didn’t have the desire to get back to his old self. He just couldn’t. “The symptoms were too overwhelming. I just felt nausea and headaches all the time, and that overpowered my personality,” says Drummond, who has been diagnosed with concussion four times. Even expressing that much to the people around him was impossible. “You want to explain that you’re not feeling well, but you’re not well enough to have those conversations.”

Others have experienced a vicious internal battle, too. For one player, who prefers to remain unnamed, it became life-threatening at times. He received a career-ending concussion while playing in the minor pros. “It’s crazy the feelings that go through your head. I get emotional just thinking about,” he says. “I had a lot of suicidal thoughts. I’d be driving to the doctor’s office and thinking to myself, ‘What if I just swerved my car into oncoming traffic?’ ” he says. He felt weak and embarrassed for having such thoughts—he only told his girlfriend and, later, his neuropsychologist about what he was going through. Those sessions helped him. “I needed to get a lot of feelings out and deal with them,” he says, to gain perspective. But he wants to resume therapy to further heal. “It’s like you get trapped in your own brain.”

Max Taylor also felt imprisoned after he received four concussions over two years while playing centre in the AHL starting in 2008. “It was a huge roller-coaster ride. I was really depressed and even suicidal. It freaked me out,” he says. “It just didn’t seem like my life was going to get any better.” The physical symptoms were so bad that Taylor, 27, took to sleeping 12 hours straight just to avoid feeling the pain. Where he used to run a mile in six minutes, he now got dizzy walking down the street to the nearest stop sign. He’d avoid sports news because it reminded him that his NHL chances were slipping away. “There were days that I would lose my mind.”

Like when he learned that the Toronto Maple Leafs, his favourite team since childhood, were looking for a centre. Taylor was invited to the training camp, but couldn’t attend because he was still experiencing concussion symptoms. He became delirious. “I did a mini-circuit in my bedroom—push-ups, body squats and sit-ups,” repeating one mantra: “Just do whatever it takes to stay in shape so that when I’m ready, I’ll be ready.” Instead, the frantic workout set him back. “I ended up throwing up and feeling dizzy for the rest of the day, and having to lay on the couch with a cold pack on my head.”

It was then, says Taylor, “that I realized my injury was denying me my opportunity. And there was nothing I could do about it.” As the physical symptoms lingered, the depression deepened. Dark thoughts crept into his mind. “I was just like, ‘Geez, why don’t I just take a knife to myself right now? Why not?’ ” says Taylor. “It just got to the point where I was like, ‘This is not what I want.’ ”

Ashamed at the “selfish” deliberation to end his own life, Taylor could only bring himself to tell his girlfriend about what he was considering. She rushed over to be with him, and soon after, Taylor began psychotherapy. That’s helped him cope with the physical and emotional pain—and to find new purpose in life without hockey. “I ultimately had to change my goals,” says Taylor, who has just obtained his real estate licence in Toronto and eventually wants to start a family.

The concussion still haunts him—he gets headaches and infrequent anxiety, for example. “I feel like it’s going to be with me for the rest of my life,” says Taylor. “But I’ve kind of accepted that. I don’t really have an option. I either live with it or I don’t. I guess that was one of the things that I had to think about when I was suicidal: can I live with this?”

That players such as Taylor felt, however momentarily, that if they couldn’t keep playing pro hockey then they couldn’t go on living is shocking—except to neuropsychologists Echemendia and Czarnota, who see “slow-to-recover” concussion patients every day. This refers to the small group of individuals whose symptoms don’t go away within a few weeks, and who often have had previous concussions. Depression and anxiety “is definitely very common for those players,” says Echemendia. Left untreated, “that spirals,” he explains, “and it can get really bad.” All the more so, adds Czarnota, among those players whose concussions are career-ending. “Their identity since they were six or four has been hockey. And if you tell somebody you can’t do this anymore? I don’t know how many regular people have Plan Bs. I don’t know how many athletes have Plan Bs.”

That’s the irony: their single-mindedness to make it to the NHL is what got these players so far in their careers; it’s also what contributed to their anxiety and depression. Grant Iverson, a neuropsychology professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of British Columbia who specializes in concussion, says that studies show the more highly athletes derive their sense of self from a sport, the greater the psychological stress they experience once injured. That worsens, he continues, the longer the physical symptoms last. Further complicating matters, Iverson adds, is the fact that concussive symptoms are so similar to those of depression and anxiety—fatigue, sadness, irritability, nervousness, confusion, trouble concentrating. It gets tricky to discern what’s concussion and what’s mental illness.

A recent brain scan study showed that “the depression we see in a concussed person at six months [post diagnosis] is very similar to the depression seen in a non-concussed person who has depression,” says Dr. Karen Johnston, a neurosurgeon at Athletic Edge Sports Medicine and professor at the University of Toronto. “This is extremely interesting, giving a lot of credibility that this is metabolic and not just what you’re imagining because you’re sad that you’re not playing hockey.” That was one of the toughest parts for the anonymous player who felt trapped in his brain. “I didn’t know if I was making this all up,” he says. “You start to question yourself.”

As Echemendia sees it, two factors explain the emotional toll of concussion. One is pure psychology: “These are guys who are used to being strong, active, physical, and then all of sudden they are having these feelings that they don’t know what to do with, they don’t know where they’re coming from. They want to lay in bed and pull the covers over their head.” The symptoms can make them feel “confused” and “frightened” and “no one can give them an exact answer as to when they will be better. It’s not like a high ankle sprain where we can say six weeks.”

The second factor is pure physiology: “It’s the direct effect of the brain injury, where you alter the brain’s function in certain areas that brings about symptoms of depression and anxiety,” Echemendia continues. Depending on what circuits are disrupted, some patients may experience “emotional disregulation,” adds Czarnota, which is characterized by sudden mood swings. “They cry easily, they may not understand physical cues from other people.” They might have an angry outburst for no good reason. This loss of control is especially hard for pro athletes who often spend years with sports psychologists perfecting their ability to manipulate their emotions to enhance their game.

However tough the emotional upheaval is on concussed patients, it’s hell for those around them, especially partners. “Now a spouse has not an equal but a dependent,” says Czarnota. “They have to care for this injured adult and their children and deal with the loss of intimacy and the physical assistance.” That can feel like a burden, and create resentment, says Johnston. While that’s understandable, “people really need to know that that’s not the person’s fault, that’s the concussion’s fault.”

Adding to the trouble is how the concussed person feels they’re perceived by those around them. Taylor says he felt “100 per cent” judged by his teammates. “Everyone didn’t believe me and was making fun of me that I have a glass head,” he says, particularly when his physical symptoms had abated, but he still felt emotionally unready to return to play. Least empathetic are the players who’ve never had a concussion. “They are going to be snickering for sure,” says the unnamed player, and thinking, “ ‘He looks fine on the outside.’ ”

Many players admit that before they were concussed, they didn’t appreciate the pain of others either. “I knocked a guy out once in the playoffs, and somebody told me that he had a career-ender, and I didn’t feel any remorse at all,” says the anonymous player. Taylor didn’t have compassion for one of his best friends. “He had problems, and he was explaining them to me, and telling me how he felt, and I was like, ‘Come on, man, you should be able to play through that.’ ”

Playing through the pain, after all, is a requirement to make the pros, just like taking one for the team. “If you’re not scoring goals, you got to chip in somehow—whether that’s blocking the shot or fighting. Otherwise they’ll find somebody else to do your job,” says the unnamed player, who once played with a broken hand. But, “when you’re dealing with pain in your body, you have your wits about you. You can put the pain out of your mind. When it’s your brain, you’re dealing with a lot of other things; it’s not just the pain, it’s the emotional stuff.”

The current treatment for concussion is known as the “rest and wait” approach—no physical or mental activity until all symptoms have disappeared. That gives the brain time to heal itself, explains Iverson. But for slow-to-recover athletes, there is a growing appreciation for how exercise may actually benefit them once they are emerging from the acute phase of injury, say Echemendia and Czarnota. Low-level activity “has a mood-elevating effect. It has a stress-lowering effect. It also has a sleep-promoting effect,” says Iverson. More research is needed about the ideal treatment for—and the prevalence of—depression and anxiety in concussion patients.

For Lindros, who now works with ClevrU, a Waterloo tech firm that’s created an enriched platform to enable online and mobile education, the science can’t come fast enough. “There have been advancements,” he says, but “it’s got a long way to go.” He wants to see more collaboration between researchers, to maximize funding and talent. He also wants to see the NHL make the game safer, either by widening the rink by 10 feet, or by reinstituting the two-line pass rule to slow down the game. But Lindros is not hopeful: “Until the league can look good by change, it won’t take place,” he says. “There’s a tremendous amount of short-sightedness.”

Players have a role, too. “The most important thing is to be honest with yourself,” says Beukeboom. “You’re the only one who knows how it feels.” That doesn’t mean players have to go it alone. In every case, the pros who spoke with Maclean’s were passionate about how talking through their struggles has benefited them. As difficult as it’s been for Taylor to let go of his NHL dream, he still hopes to make an impact on the game. “Now, the way I can contribute is to help other people out who might go through the same situation.”

In this way, Taylor will share a legacy with one of the NHL’s greatest players, Eric Lindros. It took him years to get to where he is now: “I feel strong. I feel vibrant. I feel healthy. I feel productive.” And he encourages athletes and anyone dealing with the emotional and psychological issues that may accompany a concussion to see a mental health professional. “It’s a big step to take. Most people haven’t before. Not every therapist is a good match for each individual. Just because you might not have an experience that you find helpful in the first couple of visits, stay with it, do some research, and ask around as to who other people have approached with their needs,” Lindros says. “You’ll find that there are a lot more people out there getting help than you might have appreciated.”