The loneliest deer in Niagara Falls

For a whole year, tourists have caught fleeting glimpses of a white-tailed deer marooned on a tiny island on the edge of the Horseshoe Falls. But don’t despair for the four-legged squatter.

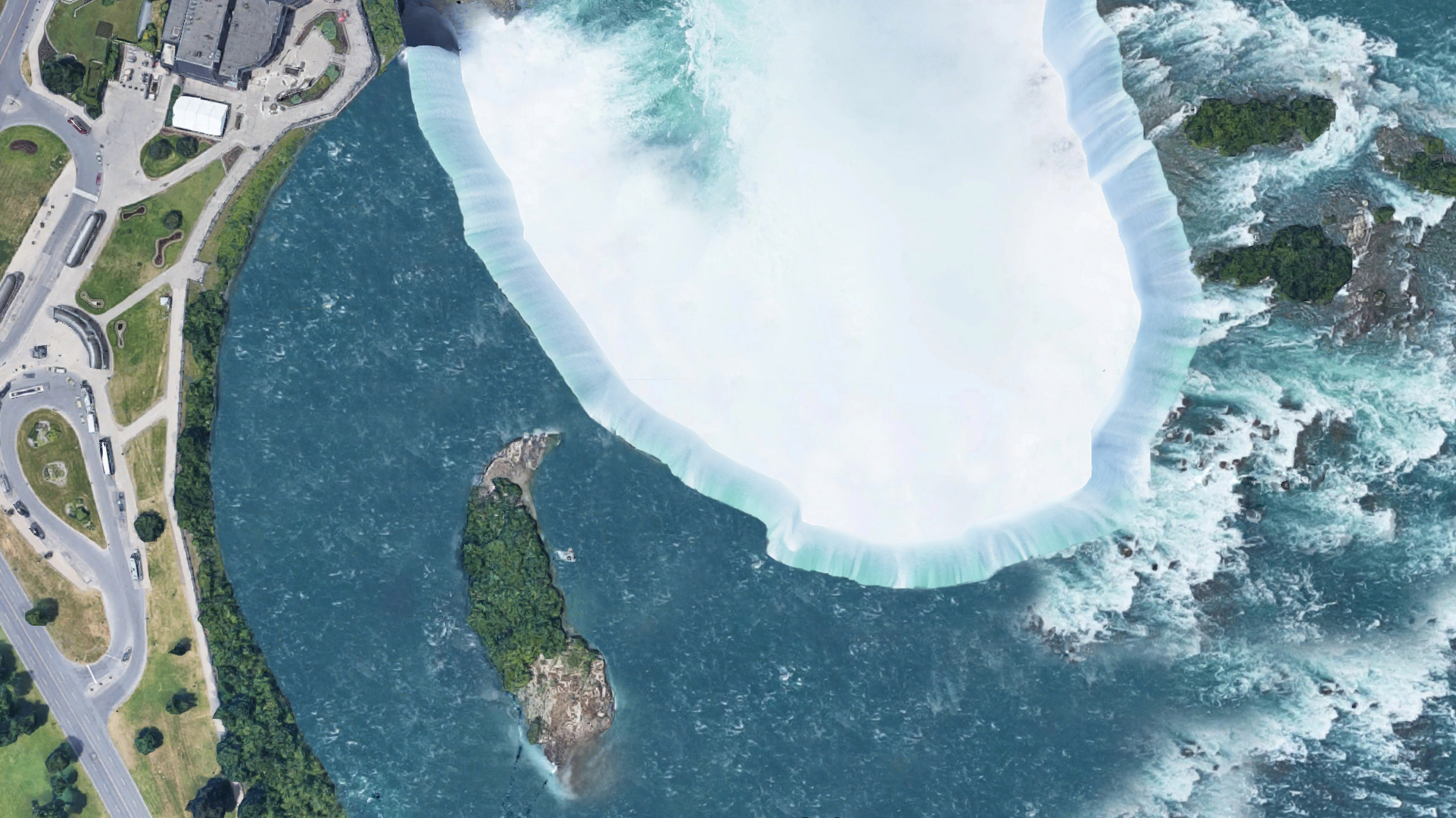

The white-tailed deer stranded on a small, nameless island next to Horseshoe Falls (Kip Finn)

Share

In the city that is home to gaudy Clifton Hill, towering casinos and a magnificent centrepiece waterfall, the prevailing modus operandi bends toward show-offs and daredevils. Niagara Falls, Ont., is, after all, where barrels used to tumble over the precipice and tightropes extended across the gorge. People watched in awe. But hiding on an island just metres from the falls, rushing water on all sides, lives the exception to the rule: a lonely white-tailed deer, a daredevil only by accident, already marooned for as long as a whole year.

Natalie Erck and John Dickinson, along with their 12-year-old son, Jack, were camping in the area in mid-July when they decided to check out the falls at sunset. They sighted the deer, which had emerged from the island’s impressive thicket of foliage, and were immediately concerned for its safety. “Our hearts started racing,” says Erck. “John called 911.”

The Niagara Parks police, whose chief has personally sighted the deer, told Erck and Dickinson there would be no rescue mission because the currents, and the proximity to the falls, posed too much of a threat to would-be rescuers. And Niagara Parks, the agency in charge of lands on the Canadian side of the river, confirms it is taking a hands-off approach: “If you try to rescue the animal, you could very easily startle it. And then it could go over the falls.”

READ MORE: The Haida Nation is teaming up with New Zealand’s snipers to kill deer and save Haida Gwaii

The provincial Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry also abides by the spirit of live-and-let-live. “The ministry does not have staff trained for a water rescue situation and does not rescue wildlife animals from environmental hazards,” said ministry spokesperson Jolanta Kowalski. “Given the location of the deer, a rescue operation would put staff and the animal at significant risk.”

Thirty years ago, local authorities sang a different tune. Back then, a small herd of deer had been grazing on a chunk of land called Navy Island, which lies a few kilometres upstream from the falls. (In 1837, the island served as the headquarters of rebel leader William Lyon Mackenzie’s failed Republic of Canada.) When American hunters scared six of the animals into the water, an alarm went up and most of the deer were saved by first responders and humane society members, who even managed to lasso a stranded doe.

By 2007, Navy Island’s deer population was so plentiful that the feds partnered with nearby Six Nations hunters on a cull. There’s even a theory that the one spotted last summer on the island nearest the falls—which may have swum downstream from Navy Island—didn’t last the winter. The current ungulate, some speculate, could be a wholly different specimen. The ministry, for the record, officially supports the one-deer theory.

Original tenant or not, despair for the four-legged squatter is probably misplaced. The island’s foliage offers shade during oppressively hot summer afternoons. The deer faces no competition for food; no obvious natural predators. Rhiannon Kirton, a master’s student at Western University who specializes in white-tailed deer movements, floats a theory: “Maybe it doesn’t want to leave.”

If midday gawkers don’t spy the deer, they shouldn’t be surprised. Kirton says the white-tailed variety are crepuscular—most active at dawn and dusk, when Erck and Dickinson caught a glimpse—and typically spend the middle of the day resting. Deer are “specialized browsers” that feed on leaves and woody shoots, she adds, and thrive on a low-protein, high-fibre diet. This one doesn’t appear emaciated, which suggests the island’s smorgasbord of greenery offers enough sustenance. “It’s probably just munching on the bushes and having a good old time,” says Kirton.

RELATED: The game-meat crisis most Canadians have never heard of

The safety of the mainland appears only a short swim away, and it’s a little-known fact that deer are good in the water. A marshy area, hidden under the embankment safeguarding tourists from the rushing water, could offer discreet refuge. That the currents surrounding the island reach 40 km/h might seem a deterrent, but Kirton says the deer might make the crossing safely if it wanted to leave.

For now, it could hardly find better real estate than the island perched near the edge of the falls, which is no less a survivor than its elusive resident. Satellite imagery dating back 50 years shows very little change to its size and shape, even as the Horseshoe Falls on the Canadian side slowly recedes at a rate of about one foot a year.

The island is currently nameless on official maps. The largest of the Three Sisters Islands, just across the rapids on the American side, was until 1834 known as Deer Island. Surely if any chunk of rock now deserves that name, it’s the one that sustains a creature who bravely clings to its shores, living a life of plenty against the backdrop of the magnificent cataract that could spell its untimely end.

This article appears in print in the September 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Room with a view.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.