Flight 752: A family torn apart

Abbas Saadat said goodbye to his family as they headed home to their lives in Edmonton. Don’t worry, they told each other. Life was good.

Shekoufeh Choupannejad (centre) with her two daughters, Saba and Sara (Perry Nelson/USA TODAY)

Share

Dr. Shekoufeh Choupannejad and her daughters, Sara Saadat, 23, and Saba Saadat, 21, were facing a long, global hopscotch day of travel—Tehran to Kyiv to Toronto to Edmonton—that would begin with a pre-dawn flight out of the Iranian capital. Shekoufeh insisted that instead of driving them to the airport, Abbas Saadat, her husband and Sara and Saba’s father, stay put as planned and look after his ailing mother.

Over a two-week vacation, the family had divided their time between Shekoufeh’s hometown of Isfahan, a city of two million people 400 km south of Tehran, and Abbas’s 35,000-person hometown of Gerash in southern Iran. Sara and Saba—sisters so close in age and in life that they existed as a matched set in the minds of everyone who knew them—spent time with both of their grandmothers for the first time in several years, and had a chance to explore their parents’ homeland, where they had only lived for a few years themselves. The family—missing only eldest son Navid Hakimi, 30, who was working on his Ph.D. at the University of Toronto—ended their trip in Shiraz in southwest Iran, where Abbas’s mother happened to be having surgery.

When the time came for the three women to make the long journey to the airport for their Jan. 8 flight, Abbas hired a private taxi to cover the first leg to Isfahan, where they stayed overnight before taking another car from there to Tehran’s Imam Khomeini International Airport.

FLIGHT 752: The victims

Abbas was back in Gerash by the time his family called from the airport around 1 a.m. to say goodbye; the plan was for him to rejoin them in Edmonton in a month or so, once his mother was on the mend. Shekoufeh, a 56-year-old obstetrician and gynecologist beloved by her patients for her caring demeanour and sharp medical detective skills, worked long hours, and Abbas loves to cook; on the phone, his daughters talked about how the food he made was tastier than their mother’s. “Come on, don’t make a joke, don’t make me laugh,” he protested, but his girls insisted. “This is true,” Shekoufeh chimed in.

By the time the three women had obtained their boarding passes, a notice had gone up that their flight, Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752 to Kyiv, would be delayed by an hour, and they worried it would stretch even longer. “I know you’re tired, but you can stand it. You are strong,” Abbas told them.

It was in so many ways an ordinary, warm family conversation from an airport departure lounge, but when Abbas looked back on it later—after the unthinkable had happened—something felt different to him during that call, and had for several days. Earlier in the vacation, when they were in Isfahan, Shekoufeh had called dozens of former classmates from high school, university and medical school and invited them to visit. They gathered together and took lots of photos, and Shekoufeh told her husband that she felt wonderful about it.

Just over a week after that airport phone call, those same friends gathered again when Abbas returned to Isfahan to bury Shekoufeh. “You don’t know your wife,” one of them commented. “I’ve known her for 26 years,” he replied. But the friend explained: “She never did [things] like that, to call everyone like that and be gathering together. It was so wonderful.” Abbas would wonder afterward, “I don’t know why she felt that way; maybe she wanted to say bye-bye to everybody.”

And now again on the phone with his family at the airport, something felt strangely freighted to him. He didn’t weep, but his voice shifted, and his wife heard it. “What happened to you?” he recalled her asking. “You cannot take care of your mom?” No, no, he said, that’s all fine. “Then why is your voice changing?” Shekoufeh asked. “It’s because I’m not with you,” he answered.

‘They wanted a simple life’: Remembering Razgar Rahimi, Farideh Gholami and Jiwan Rahimi

‘Her heart was like the ocean’: Remembering Niloufar Sadr

‘They were both go-getters’: Remembering Arvin Morattab and Aida Farzaneh

She reassured him: it’s only a few weeks, and then we’ll book you a flight back to Edmonton. Abbas agreed, but Shekoufeh still seemed to hear something that left her unsettled. “Okay, then why are you worried?” she asked. He had no answer at the time.

“You’re talking about instincts, but you don’t think it—without thinking, without saying, without knowing,” he reflected later. “Without knowing.”

As Shekoufeh prepared to hang up, Sara’s voice grew louder in the background, asking to speak to her father. When her mother handed the phone over, she told him to look after her grandmother and himself. “Sara jan, take care,” Abbas said, using the Farsi term of endearment meaning “beloved one.” He wished his elder daughter luck, as she was getting ready to head back to San Diego, where she had moved recently to continue her studies in clinical psychology.

Then Saba clamoured for her turn on the phone. The University of Alberta student was set to graduate in April and was busy completing applications for medical schools all over Canada, but hoping to stay close to home. “Don’t worry, definitely I will pass the exam,” Abbas recalled his younger daughter assuring him, adding, “You have done everything for us.” Abbas replied, “That’s the only thing I need, Saba jan. Nothing else.” Recalling this conversation weeks later, Abbas dissolved in tears.

Ten thousand kilometres away in Calgary, where it was mid-evening, Daniel Ghods-Esfahani had just arrived home, showered and eaten dinner. The University of Calgary medical student had been dating Saba for three years, and now they texted back and forth while she waited at the airport in Tehran and he sat in front of his computer, preparing to do readings for class. The two had met in Edmonton, where his family lived, on New Year’s Eve in 2017, when the Saadat sisters issued an open invitation through mutual friends to a party at their house. They didn’t know Ghods-Esfahani, but that night and on the others that followed when a sprawling group would hang out in their basement, he was bowled over by their capacity to welcome everyone. “They invited me with open arms without even knowing who I was,” he said. “That’s where our friendship started.”

Afterward, Ghods-Esfahani’s descriptions of his bright, caring girlfriend and her kind-hearted family would carry an unmistakable sun-moon-and-stars glow. From the outside, it would be impossible to disentangle how much of that was about the relationship itself and how much about the horrifying way it ended.

Flight 752 finally got underway just under an hour after it was supposed to. In the weeks that followed, there would be anguished, furious global recriminations over why any civilian airliner had taken off from Tehran that day. The overnight hours in the region had been chaotic. Iran had fired missiles at U.S. positions in Iraq in retaliation for a drone strike ordered by President Donald Trump that had killed a top Iranian general, Qassem Soleimani, five days earlier. The preceding week had been an abrupt and capricious escalation of long-simmering tensions between the United States and Iran.

By the time Sara, Saba and Shekoufeh’s Ukrainian Airlines flight taxied onto the runway, Iranian military posts were on high alert.

Six years earlier, Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur was shot down by a surface-to-air missile over Ukraine, killing all 298 people on board. A subsequent investigation by the Dutch government warned, with tragic prescience, “Practice shows that states in which there is an ongoing armed conflict will not implement restrictions for their airspace on their own initiative.”

And so at 6:12 a.m. local time, Flight 752 lifted off from the tarmac and climbed into the sky, heading northwest. The plane reached an altitude of 7,900 feet two minutes after takeoff, but then radar contact abruptly cut out. Amateur video recorded from the ground and later obtained, verified and analyzed by the New York Times shows the deadly pinprick of a missile arcing toward the plane, and then a brilliant split-second explosion as the missile detonates and seems to send the plane ricocheting on a different trajectory. It would eventually come to light that the person on the ground must have yanked out their phone and started filming because they had already witnessed another missile launch into the sky half a minute earlier. What they caught on their camera was the second strike; the first is what knocked out the radar.

The Boeing 737, now consumed by flames, changed course in an apparent attempt to head back toward the airport. Another bystander video obtained by the Times shows the plane falling like a horrific comet and then the flare of a second mid-air explosion as the plane angled inexorably toward the ground. There was a blinding flash when the jet struck the earth and then the sight of a nightmare landscape of plane shards and hungry gobs of fire.

News of the crash travelled fast, sending a wave of devastation across Iran and abroad. In Canada, where it was still late on the evening of Tuesday, Jan. 8, Iranian-Canadians’ phones from coast to coast began buzzing with WhatsApp and Telegram messages. First, the news was simply that a plane had crashed near Tehran. Then, the names and faces of the people on the flight began to emerge.

In Calgary, Ghods-Esfahani tracked Saba’s flight as it took off. Then he kept checking its status: 15 minutes, 45 minutes, an hour—the virtual version of his girlfriend’s plane was safely in the air, carrying on as it should. He got a text from his mother, asking what flight Saba and her family were on. He answered 752 and asked why she wanted to know, but she didn’t answer. Then a friend contacted him to ask the same question, and Ghods-Esfahani grew worried and demanded an answer; his friend asked if he’d heard what had happened. “I thought that he was talking about the missiles that were fired on American bases in Iraq,” Ghods-Esfahani recalled later. “But he said there was a plane crash outside the airport in Tehran.”

He searched online for more information and realized immediately that the downed flight was Saba’s. He FaceTimed with his mom, breaking down crying, and then told her he was coming back to Edmonton. Ghods-Esfahani called a few friends, hastily packed a bag and drove toward home in blizzard conditions so he could be with his family.

His final text to Saba earlier in the evening asked if she was on board yet. The message didn’t go through, but at the time he thought nothing of it, figuring the airport WiFi had cut out as she boarded the plane. “I just thought she was coming back,” he said later. “I was waiting for her to text me back when she got to Ukraine.”

Around 8 a.m. local time, Abbas’s phone rang in Gerash. It was his brother-in-law calling from Isfahan. “I have bad news for you,” he said, and informed Abbas that a flight had crashed near Tehran. Abbas’s brain rejected the inconceivable and grasped for some mercy in the circumstances. “I said, ‘No, no, it hasn’t happened, I don’t believe it, no,’ ” he recalled later. “Maybe it was a different airline; maybe it was a mistake.”

He began calling the airport, various airlines and government officials—anyone he could think of who might give him an answer. Lines were busy; no one picked up or offered help.

At one point, Abbas opened WhatsApp and called Saba’s phone. It began ringing, and for a moment, he thought, “No, they’re not dead.” But there was no answer, and when he dialed Shekoufeh and Sara’s phones, the calls didn’t go through.

Desperate for answers and too distraught to drive himself, Abbas called someone he knew and hired him to drive him to Tehran. It would be an excruciating 14-hour drive. “When I got the call, I thought it was the end of my life, too, and I have nothing left to lose,” he said later. “I lost everything.”

Soon after the crash, Ukraine’s embassy in Tehran issued a statement saying that preliminary information suggested that engine failure, not a missile attack or an act of terrorism, had caused the tragedy. But then the embassy swiftly removed that statement, saying any comment about the cause was “not official” and the factors behind the crash were still “being clarified.”

Almost immediately, OPS Group—a network of pilots, dispatchers and air traffic controllers that promotes information sharing in plain language—offered its own preliminary assessment. “We would recommend the starting assumption to be that this was a shootdown event,” said a blog post signed by founder Mark Zee, “until there is clear evidence to the contrary.”

Zee’s early assessment had more to do with risk management than diagnosis. “Images seen by OPS Group . . . show obvious projectile holes in the fuselage and a wing section. Whether that projectile was an engine part, or a missile fragment is still conjecture,” he admitted.

Whatever the cause, OPS Group’s advice to airplane operators was to stay away from Iranian airspace.

On the long drive to Tehran, Abbas continued trying to reach someone, anyone, who could tell him what had happened, but it was fruitless. Beyond those desperate efforts, he felt paralyzed by grief and shock. “I was crying the whole way,” he said. “I cannot talk, I cannot move, nothing.”

Twenty-five years earlier, Shekoufeh had been in her final year studying obstetrics and gynecology in Isfahan, and Abbas was living in Dubai and working as an orthodontist when they met in the early 1990s. A family member who taught at the university where Shekoufeh was studying told Abbas, “She’s perfect: so caring, and she’s very honest, and she’s very happy. She’s a great human,” and introduced the two.

Abbas wasted little time. He returned from Dubai a month or two later to propose, and within weeks they were married and returned to Dubai together, where Shekoufeh worked for the government and in a charitable organization’s hospital. She was unfailingly sunny and generous, quick to dole out loving gestures and warm advice to her family and anyone else in her orbit. “Always, always, always, always smiling,” Abbas said.

Their family included Navid, Shekoufeh’s son from a previous relationship, and soon added Sara, born in 1996, and Saba in 1998. The girls were born in Dubai, and the children spent the early years of their childhoods there. They attended English-language kindergarten and then Oxford School Dubai, a private school that follows a British curriculum.

By this point, Abbas had been gone from Iran for years. But he is the eldest of nine children, so when the brother next to him in line, a surgeon, developed ALS and the family needed help, Abbas moved back home. His family spent the next few years in their home country—Abbas ran a clinic in Tehran and Shekoufeh worked at various hospitals in Isfahan—but their jobs and family commitments involved long commutes that wore them down. When Abbas finally worked up the nerve to tell Shekoufeh that it was all too much and he thought they should move abroad, she confessed that she’d reached the same conclusion.

They chose to settle in Halifax because Abbas had two cousins there already, and the family relocated permanently in 2011. They loved the scale and tranquility of Halifax after enduring the frantic pace of Tehran’s eight million inhabitants.

Shekoufeh and Abbas had to write a series of exams to be certified to practise their specialties in Canada. Abbas thought his English was strong, but the specialized language in the biology textbooks made studying an arduous slog for him. Shekoufeh worked through her examinations more easily and told her husband, a decade older than she was, that it was time for him to retire. Financially, this idea worked for them, so Abbas volunteered with the Red Cross during local emergencies and went back to Iran occasionally when his family needed help, while Shekoufeh worked to establish her career in Canada.

ESSAY: Walking in the footsteps of the victims of Flight 752

The family had been in Halifax almost three years and Shekoufeh had completed all the exams necessary to practise as a resident with supervision in Canada when she got word of a clinic in Edmonton that needed an OB/GYN, so the family moved to Alberta. Abbas proudly recalled Shekoufeh’s superiors at the Northgate Centre Medical Clinic being so impressed with her skills that they joked she would take their jobs because, accustomed to working with little assistance in Iran and Dubai, she could complete a Caesarean section in 10 minutes flat.

The family obtained their Canadian citizenship in 2015, and things were happy and settled. “We had a nice life, especially once we came to Edmonton. She started working, so she was so happy . . . She was dedicated to her job; she loves her job, so she was so happy in that city,” Abbas said. “We were a very happy family.”

Even with a busy work schedule, exams to prepare for and a family to take care of, Shekoufeh was renowned for being active in her community. Friends say she donated a considerable amount to fundraisers, including one to support victims of a flood in Iran last year and the rebuilding of two schools in the area. One of the fundraising initiatives in which she got involved connected her two years ago to Shayesteh Majdnia, an Iranian who grew up in Dubai and works as an HR specialist in Edmonton. After being introduced by a mutual friend, they became close friends. “From that time, I knew she was the one if I needed anything,” Majdnia said. “She’s a phone call away, always.”

To Navid, his mother imparted a comforting sense of order in life. “She was relentless in making everything right,” he said in an email. “Every time in my personal life or during my studies or research when I had a failure or difficult time, she magically gave me the advice and comfort to figure things out.” And he came to realize she filled a similar role for colleagues and friends, her extended family in Canada and Iran, as well as newcomers to Canada who needed a hand to find their place and Edmonton’s Middle Eastern community at large. His mother was also the most intelligent person he knew, finishing high school by age 15 and ranking fourth nationally on her Iranian medical board exams, he said. “I never knew how she managed everything at the same time,” Navid marvelled. “Her energy never depleted.”

Sara and Saba were just 17 months apart in age, and they grew up and moved through school and then life in Canada so closely intertwined with one another that their identity as sisters was central to how other people saw each of them individually. Ghods-Esfahani believed that watching their parents establish themselves in Canada shaped how the sisters saw their parents and the value of hard work. “This is the reason why family was such a big component for their identity,” he said in a eulogy later.

Last May, when Sara graduated from the University of Alberta with a degree in psychology, their maternal grandmother visited from Iran; it was the first time Ghods-Esfahani’s mother had met the whole family. “Wow, did you see how their two daughters are standing behind their grandmother, like two lions, supporting her?” she commented to her son later. That tight network of support was central to who the Saadat girls were. “I can’t begin to picture anything about them without the idea of their family coming to my mind,” Ghods-Esfahani said.

But as close as the two women were, they were very different, too. Quiet and intuitive, Sara was, in her father’s words, “a very peaceful girl.” Navid described her as an introvert who connected deeply with those closest to her. “Sara was the most sympathetic person I knew,” he said. “She always listened and deeply cared, shar[ing] any emotional burden with whoever turned . . . to her.” When she told her father she wanted to study psychology as an undergraduate, the idea made perfect sense. “If you love it and you can help human beings, why not?” he remembered telling her. But in their family, merely showing up was not the plan. “Whatever you want to study, I am asking you to be the best, not only to graduate,” he added. Last fall, Sara began a clinical psychology graduate program at Alliant International University in San Diego.

Saba, however, wanted to follow her mother’s footsteps into medical school. During her undergraduate studies in biological sciences at the University of Alberta, she completed a student research project at the Women and Children’s Health Research Institute. Abbas laughed as he recalled his younger daughter joking with her mother about their future. “You know, one day we’ll go to the same operating room, and we’ll see who can do a better job,” he remembered her saying. “She believed in herself, but she never told anybody, except when joking around with her family,” Abbas said. “She wanted us to be happy; she tried to make us proud.”

To Navid, there was no coincidence in Saba wanting to measure her future self against her mother, because his younger sister’s focus and determination always reminded him of their mom. “She was also extremely kind and had a magnetic personality,” he said of Saba.

Her research supervisor, Meghan Riddell, described her in a tribute on the university’s website as “a Ph.D. disguised as an undergraduate” and recalled that when she completed an oral defence of her research, the panel could not find a single question that she wasn’t prepared for. “It became almost comedic because she had predicted everything the three different Ph.D.s in the room would ask,” Riddell said.

But as impressive as Saba’s intellectual gifts were, it was the warmth and empathy of a young woman who tutored with the Iranian Heritage Society of Edmonton, volunteered to teach piano to disadvantaged kids and filled holiday hampers for families in need that made her unforgettable. “I would be incredibly lucky to ever encounter a student like her again,” Riddell said.

That capacity and drive to care for other people in their orbit was shared by all three women in the family. Ghods-Esfahani remembered a time two years ago when his parents were back in Iran for a visit and his name suddenly came to the top of a waiting list for the sinus surgery he needed. “I was at university, I was alone, I had not experienced anything like that,” he recalled. “Saba was the first person to support me through this and told me, ‘Just go do it; I will be there for you.’ ” She drove him to the hospital in the early morning and was waiting for him when he came out of surgery. She, Shekoufeh and Sara fussed over him in the days that followed with food and company. “The way that she cared for me, I knew she was very special, and I knew that I’d never be able to lose her,” he said.

Back in Iran, as the day of the crash wore on, Abbas was still frantic for confirmation and closing in on Tehran. When he and his driver reached the city, they went directly to Imam Khomeini International. He approached the information desk, and they confirmed the horrible news that the crash had occurred. But information about the cause was hopelessly muddled; depending on who he talked to, it was the fault of the U.S., Israel or some mechanical failure. “Nobody official . . . comes to say ‘Hi, I’m sorry,’ ” he recalled of how adrift he was. “Or anything. Nothing at all.”

Someone told him that to complete the DNA testing that would identify the remains of the crash victims, he needed to go to Isfahan, his wife’s hometown, so he and his driver headed there. Shekoufeh had attended classes and taught at the university where Abbas went to complete the testing; the doctors did not know him, but they remembered his wife and knew what had happened, and they treated him with great gentleness and respect. He called Shekoufeh’s sister to take a DNA test as well, but the doctors said it would take a month to get a match from a sibling, so his sister-in-law brought Shekoufeh’s mother in for testing instead. “One month I cannot wait,” Abbas recalled thinking. “I cannot wait.”

By evening in Ottawa on the day of the crash—the middle of the night in Iran—Prime Minister Justin Trudeau gave a press conference in which he announced that of the 176 people killed, 63 were Canadians—a number that would eventually be adjusted to 57. “While no words will erase your pain, I want you to know that an entire country is with you,” he said to their loved ones. “We share your pain.”

Travel restrictions and sanctions made Kyiv a popular connection point for Canada’s large Iranian diaspora when they visited their homeland. In fact, the concentric circles of grief, love and loss that would stretch between Canada and Iran were even more profound than the 57 Canadian citizens who had perished, Trudeau soon made clear. “About an hour ago, a Ukrainian Airlines plane just landed in Toronto from Kyiv,” he said softly. “According to the airline, there were 138 passengers who weren’t on that flight because they died in the crash on the earlier leg of their travel.” Three-quarters of the people who perished in the crash were, like Shekoufeh, Sara and Saba, destined for Canada.

Less than 24 hours after the crash, preliminary findings published by the Iran Civil Aviation Organization blamed a “technical error” for the disaster and cited eyewitness reports that claimed the aircraft caught fire and appeared to turn back toward the airport before it hit the ground.

But as soon as international reports emerged that the crash had not been the result of a mechanical failure or the fault of the airline, Abbas knew something was deeply wrong. “The first three days they were denying it,” he said. “Just imagine.”

The following day, on Jan. 9, news stories began to break, beginning with Newsweek, quoting anonymous sources who said that 752 had been taken down by an Iranian missile.

Within hours, Trudeau was back behind that same podium in the National Press Theatre in downtown Ottawa. “We have intelligence from multiple sources including our allies and our own intelligence. The evidence indicates that the plane was shot down by an Iranian surface-to-air missile,” he told the assembled reporters and cameras. “This may well have been unintentional.”

With that statement, Trudeau essentially became the first named source on the story that rocketed around the globe. American and British officials soon confirmed it was “highly likely” that the plane was shot down amid the hostilities in the region that night.

Iran’s initial response was a flat denial and a belligerent challenge. “What is obvious for us and what we can say with certainty is that no missile hit the plane,” said Ali Abedzadeh, head of Iran’s national aviation department. And, he added, if Western leaders like Trudeau were certain that is what happened, then they should show the world the proof.

But two days later, amid mounting international pressure and—more crucially for the regime—tens of thousands of its own furious citizens marching in the streets—Iran admitted that the plane had been downed by one of its own missiles after it was mistaken for a hostile entity. “Human error at time of crisis caused by U.S. adventurism led to disaster,” Foreign Minister Javad Zarif wrote on Twitter. “Our profound regrets, apologies and condolences to our people, to the families of all victims, and to other affected nations.” The message ended with a broken-heart emoji.

Even with the admission of the cause of the crash, there were persistent and widespread international worries that Iran would run an insular investigation, sealed off from the outside world. It wasn’t at all clear who, aside from the country’s aircraft accident investigation bureau, would have access to the sensitive flight data and cockpit voice recorders—the “black box” data—or even the crash site itself.

Amid the wreckage, investigators did eventually recover the data, which would provide a detailed look at the plane’s brief flight, including chatter in the cockpit and the aircraft’s precise speed, location and altitude. But the black box was damaged, and because Iran lacked the technological capability to analyze the compromised data, pressure would mount for the country to send it to France or Ukraine for processing. Iran would show a distinct and protracted disinclination to do any such thing.

For Abbas, the reluctance of his homeland to admit even the most glaring facts about the cause of the crash was additionally wounding. “They were denying it and they told us the truth after three days. That is the main thing that makes me mad,” he said. “I don’t know if it was a mistake or not a mistake, whatever it was—they could tell honestly; it was a mistake and we did it, not the U.S. But still, they are blaming.”

Five days after the crash, a memorial at the University of Alberta drew a crowd of over 2,500 people who braved bone-chilling temperatures of -37° C to mourn and remember students, faculty and alumni who lost their lives, including Sara and Saba. Dignitaries including Trudeau, Minister of Foreign Affairs François-Philippe Champagne and Alberta Premier Jason Kenney attended.

The campus gymnasium, usually emblazoned with the yellow and green colours of the university’s sports teams, was covered with flower wreaths and rows of chairs filled with tearful mourners dressed in black. Behind them, more people filled the bleachers, and a line of hundreds remained outside waiting to be let in. At the front of the room, a slide show played on a loop displaying the names and photos of the lost: there was Sara, radiant at her graduation, and Saba with a soft smile on her face and a lake stretching out behind her.

The previous day, Shekoufeh’s friend Majdnia had organized a private memorial service that she thought might attract a few dozen people; instead, hundreds turned up from Edmonton’s Iranian community and beyond. The activity room of an apartment building in south Edmonton was packed with mourners; a projector displayed photos of Shekoufeh, Sara and Saba—family photos, vacations and selfies with friends—as sombre Persian music played. “She never got tired of helping,” Majdnia said of her friend, noting that she was due to write her final medical board exams for independent practice in April.

Ghods-Esfahani delivered an emotional eulogy at that event, and he finished by trying to grapple publicly with the scale of an unimaginable loss. “I don’t even know what to say. I love them all so much, and I know as you guys all do, they were very loved in this community, and they’ll always have a very special place in all of our hearts,” he said. “The best thing we can do is strive to be as kind, caring and generous as they were.”

It was not until a week after Flight 752 was blasted out of the pre-dawn sky that officials told Abbas—who had spent the first few agonizing days in Isfahan with Shekoufeh’s family before returning to Gerash to be with his own—that a DNA match had been made and he could claim the remains of his wife and two daughters. The raw pain of the circumstances was exacerbated by the wait because Muslim burial customs call for swift closure. “We believe once they die, we say it’s not good to wait,” Abbas said. “You have to pray right away, you have to wash them . . . and then they bury them really fast.”

His brother-in-law was in Tehran, so he escorted Sara and Saba’s bodies back to Gerash for burial, while Abbas rode in the front seat of the ambulance that carried Shekoufeh back to her hometown. There was little relief for him in the moment. “I feel so sad. They killed them, you know?” he recalled thinking. “They killed them.”

On Jan. 16, the day Navid arrived in Iran from Toronto, they buried Shekoufeh in her hometown of Isfahan. Her entire side of the family was there, along with many of her former colleagues from the university; in all, Abbas estimated that 1,000 people turned out to say goodbye. Following the burial, they went to a restaurant to observe the custom of hosting funeral visitors for a lunch, and immediately afterward Abbas drove nine hours to Gerash to bury his two daughters alongside his family.

His hometown is a small city where everyone knows everyone else, and it seemed to Abbas that half the town attended the funeral, joining him for prayers at the biggest mosque in Gerash in the morning, before walking four kilometres alongside him to the cemetery. “My two daughters, we went to the grave to put the bodies, and I was trying to go to put their bodies there, so they can take a rest,” he says. “And they did not allow me; they say, ‘Let us do that.’ ” The town mourned with him, but Abbas was so numb with grief that he couldn’t feel any of it. After the funeral, he spent hours on the phone with people who called to offer condolences.

As part of his own mourning, Navid posted a photo of his sisters on Facebook. The two women are the only people in the frame, sitting side by side on the trunk of a black Mazda 3 in an empty parking lot in Edmonton, each holding a paper cup containing a small mountain of ice cream.

Sara and Saba ham it up, eyes closed beatifically and tongues stuck out in appreciative greed toward the treats they are about to devour. They are carbon copies of each other: right legs crossed over left at the same angle, arms held up in mirrored poses. The setting summer sun bathes them in a glow so soft and golden that it seems to emanate from the air around them.

“Sara, Saba. I was always jealous of your bond,” Navid wrote. “Even death could not take you apart.”

The family’s vacation in Iran had been a reunion: Abbas had been back home tending to his mother, but they would all be together for two weeks over Christmas break. Shiraz, where they finished their trip, is an ancient place considered a cradle of Persian culture. The city’s calling cards are all about the treasures of the heavens brought down to earth: elaborate gardens, wine, mosques built of light and stone lacework, intellectual pursuits and poetry. The tombs of the poets Hafez and Saadi, two giants of medieval Persian literature, are the biggest attractions; their writings are so revered that their final resting places are treated as pilgrimage sites.

On that last trip, Sara and Saba got to take in the tourist sites of Shiraz for the first time, and they were captivated. “Daddy, why did you not bring us to Shiraz to see Hafez and Saadi? It’s such a beautiful place,” Abbas recalls his daughters asking after they’d visited the famous mausoleums. “I’ll bring you back in the summer when you have more vacation time,” he promised.

Hafez lived in Shiraz in the 1300s, and virtually nothing is known of his life. The ecstatic spirituality and teeming humanity of his poetry, though, is so adored that it’s treated as an oracle by Persians in need of guidance: some will throw open a page, point to a random line and see what Hafez has to say about what is weighing on them at that moment.

His poem A Great Need reads:

Out

Of a great need

We are all holding hands

And climbing.

Not loving is a letting go.

Listen,

The terrain around here

Is

Far too

Dangerous

For

That.

—with files from Nick Taylor-Vaisey

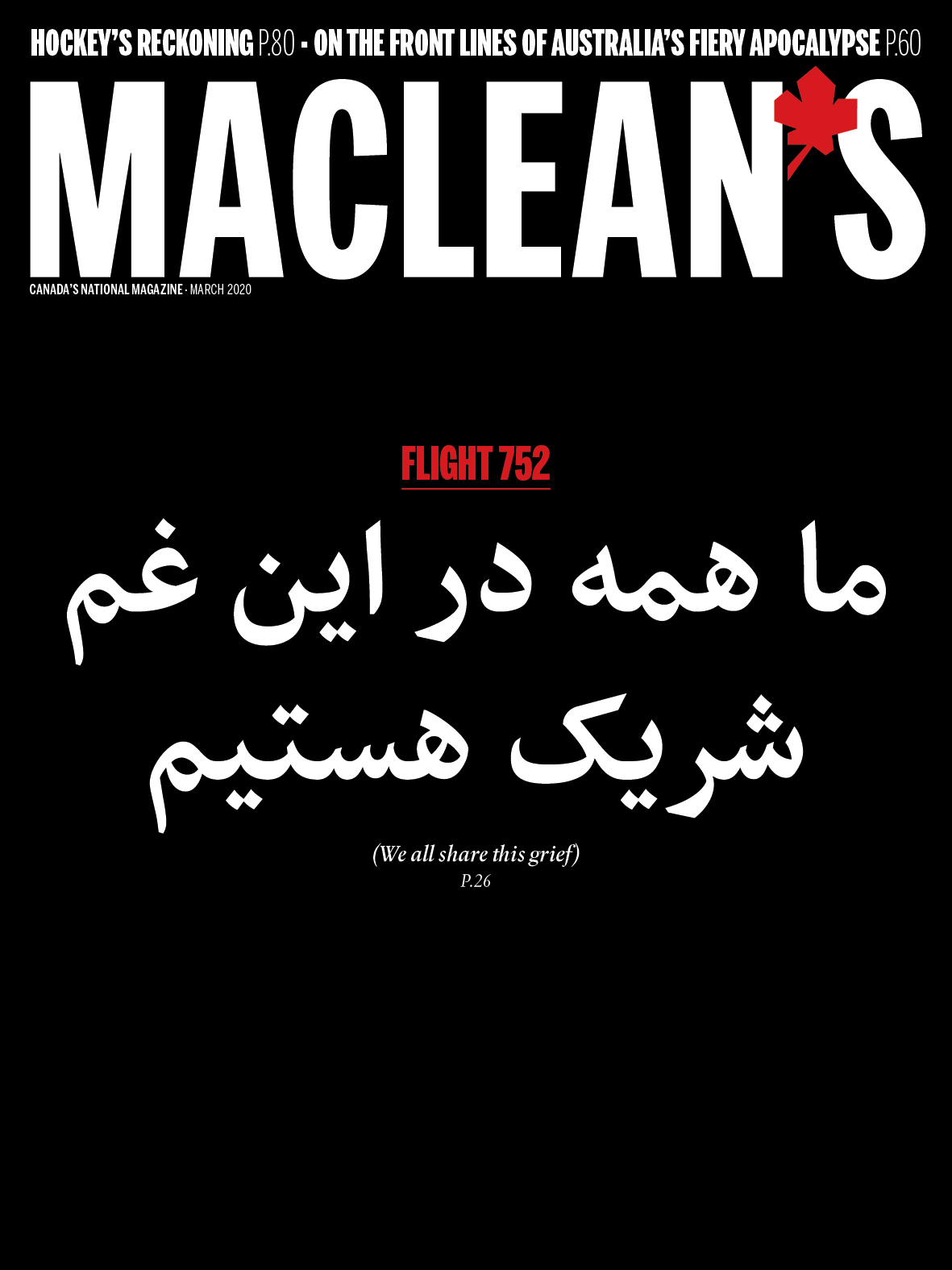

This article appears in print in the March 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “The beloved ones.” On our cover this month, we offer a Farsi expression of condolence to illustrate a collective spirit of national devastation after the downing of Flight 752. Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.