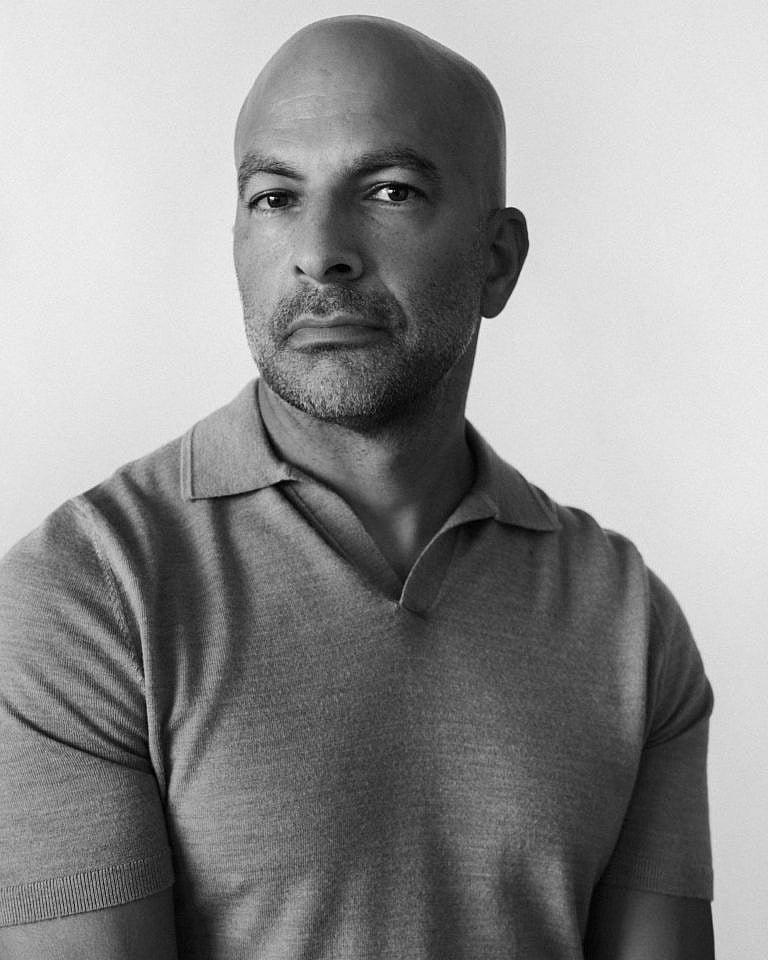

Longevity expert Peter Attia can help you cheat death—for a while

“We have it better than the king of England did 500 years ago! I think about that when I’m distressed about the insignificance of my life, and that, in 30 or 40 years, I’ll be dead.”

(Photograph by Bryan Schutamaat)

Share

When Toronto native Peter Attia was working as a surgical resident at Johns Hopkins, he was haunted by a very specific stress dream: he’d see himself frantically running around a city sidewalk, trying to catch eggs that were falling from the sky. Many times, they’d splatter on the pavement—and all over his scrubs. Attia, who was training to be a cancer surgeon, later realized the eggs symbolized patients, people whose disease had advanced too far to treat.

That helplessness caused Attia to quit medicine for a time, eventually returning to practice armed with a fresh idea he called “Medicine 3.0”—a visionary approach to health care that manages disease before it starts, using a combo of exercise, nutrition, sleep, the occasional supplement and emotional wellness. It’s also the thesis of Outlive, his new, wildly popular, death-defying book.

Between Early Medical, his Austin-based clinic (where he’s treated several members of the Marvel Cinematic Universe) and The Peter Attia Drive (his podcast, downloaded 75 million times), Attia is widely regarded as a rare credible voice in an easy fix–filled health climate, one packed with rapidly aging boomers way more likely to see Dr. Google before their own GP. But Attia’s biggest selling point is, perhaps, his vulnerability. As a physician, he can prevent the worst. As a man, he knows all too well that he’s fallible.

Outlive is about prolonging life and, by extension, delaying death. How much of your work is rooted in a fear of your own mortality? Let’s start off with something light and fun.

Today, I don’t think about that nearly as much as I do about maximizing quality of life, but when I started working on the longevity problem a decade ago, not dying was my only motivation.

Relatable, but what were you outrunning?

Subconsciously, at least, I knew I wasn’t living a great life and that I needed more runway to make things right. I was in a chronic state of anger and detachment and not being a great dad or husband. Most of my energy was focused on achievement, rather than who I was. People like that are difficult to be around.

READ: Superbugs are overpowering antibiotics. We should fight them with phage therapy.

I’m sure many people look at you like, “Here’s an ex-surgeon who wears tight tees and eats his perfectly portioned steamed chicken and greens every day. Peter Attia has it all together!” It would be quite easy to be annoyed by your seeming infallibility if you weren’t so candid about your struggles, like work obsession, self-loathing and a stint in outpatient rehab initiated by a serious ultimatum from your wife. Is it hard to talk about these less-than-optimal moments when your job is optimization?

They’re not easy to talk about in general, but you can discuss your issues without just saying, “These are my immutable characteristics, so deal with it”—which, by the way, is all I did for many years. One of the big drawbacks of being a perfectionist is that you’re less likely to try to do something hard, like change.

So you’re a self-diagnosed perfectionist?

Oh, absolutely.

That’s an advantage, in a way, because some of your patients are literal superheroes. Hugh Jackman has said he trusts you with his life, and you ran the genetic test that revealed Chris Hemsworth’s predisposition for Alzheimer’s, which prompted him to go on hiatus. How are you processing the transition from regular doctor to celebrity-doctor-slash-guru?

Sometimes people say “celebrity doctor” as a compliment and other times, it’s disparaging, though I’m not taking what you said that way. The fame part just doesn’t register. Chris and Hugh are patients like everyone else. Everybody bleeds the same way and everybody’s gonna die. Heart disease doesn’t care how famous you are.

You’ve spoken about the fact that you descend from a line of men who dropped dead in their 40s and 50s—mostly from heart disease. At 50, you’re almost out of the danger zone. Do you feel like you can relax a bit?

I had the advantage of knowing what drives the pathology of the disease that wreaked havoc on our family. Those other men didn’t. Plus, I figured it out at 35, so I took the necessary steps to reduce my risk. It might sound ridiculous, but cardiovascular disease isn’t even on my radar anymore. I’m far more worried about cancer or dying in a car accident.

Outlive’s success is a testament to the universality of those worries—the book has hovered atop the bestseller lists for months. I told five people I was interviewing you, and all of them used words like “love” or “obsessed.”

No one said they hated me! That’s awesome.

It seems like anybody can get famous via a podcast these days, but not all podcasters have an MD from Stanford. Your shows are heavily fact-based and granular—one episode is just a deep dive on olive oil. Are you ever frustrated with how casually your podcasting peers seem to push unregulated health products, like supplements?

The signal-to-noise ratio in the wellness industry is quite low. The supplement industry, in particular, is very predatory. And in the podcasting space, conflicts of interest are almost never disclosed, and content producers create their own ads. When it came time to monetize The Drive, we decided to sell access using a subscription model. I also have a page on my website that lists any companies I invest in. I’d like it if no podcaster ever spoke about anything without saying, “I’m getting paid to talk about this.”

RELATED: How I Plan to Die

You’ve experimented with health trends yourself. Have you ever been taken in by a fad that you later found out was bunk?

About 10 years ago, I became very interested in synthetic ketones, which are fat-burning dietary supplements. At the time, they weren’t commercially available. I had to get them made in a lab. They were incredibly expensive and bad-tasting—like drinking jet fuel. They’re not bunk, but they don’t appeal to me. I’ve also tested apple cider vinegar while hooked up to a continuous glucose monitor. It’s not worth the hassle.

If you’re someone who wants to stave off death, you’ve never had more options with which to biohack yourself: step trackers; bespoke, mail-order probiotics; spitting into a tube and sending it off to 23andMe. What’s worth the hassle, and what’s just…capitalism?

The question is: do people really think that, by spitting in that tube or taking a probiotic, they’re buying immortality? A lot of the time, it’s just, “I don’t have control over the big thing—which is how my life is going—so I’ll fixate on this thing I can control.” What we’re witnessing is a culture of distractibility—or taking supplements—instead of doing what is, hands down, the most potent behavioural modification that impacts the length and quality of your life: exercise.

I was worried you’d say that. What do you do for exercise?

I’m happy to tell you, but I don’t want someone who’s reading this to think, If I’m not doing what Peter’s doing, there’s no point. I also don’t want people to say, “Well, Peter does this. He’s a bit of a psycho.”

…what is “this”?

I probably spend 14 hours a week riding my bike, doing strength training, stability training and rucking—that’s walking while carrying heavy weights on my back.

Do you at least bring your phone?

No. I also go out at the hottest time of day, which, in Austin, is around 4:30 p.m. The backpack weighs anywhere from 50 to 80 pounds. I’m not out there having a field day.

Do you derive a perverse joy from the difficulty of it?

The enjoyable part is the silence. I’m also getting the psychological benefit of doing something challenging. When I’m done, I jump into a tub of freezing-cold water for six or seven minutes.

Sounds delightful.

I always want a reminder of how good I have it; being really uncomfortable every day is a great way to get that. Living in Canada or the U.S.? Being affluent? Educated? Always having food? Nobody’s trying to kill us? We have it better than the king of England did 500 years ago! I think about that when I’m distressed about the insignificance of my life, and that, in 30 or 40 years, I’ll be dead.

Okay, but recently, on the American Optimist podcast, you said you “wouldn’t want to live in Canada if your life depended on it,” because you can’t get anything done in our health-care system. I might have reacted more defensively to that comment a few years ago, but less so now. Are you ever tempted to move back and try to fix things?

No. I’ve been in the U.S. for more than half my life now. The U.S. and Canada each do something exceptionally well that the other does horribly. The U.S. optimized for quality. There’s a reason that every single person with means comes to the States when they want the best care. But it’s an unforgivable sin that some American citizens will go bankrupt to afford treatment. (That’s the Canadian in me.) In Canada, we optimized access: nobody gets health care all that fast, but when we do, we keep costs low. And the care is really good.

So what’s the fix?

It’s frustrating that we can’t come up with a hybrid system. When I see my brother, who lives in Toronto, having to fly outside of Canada to get a procedure done—one that I could get done here within a day—there’s a problem.

After your parents emigrated from Egypt to Toronto, your dad worked as a stockbroker by day and ran a Middle Eastern restaurant in the city’s suburbs by night. I know you don’t believe genes seal our fate, but you’ve clearly got his work ethic. Do you see your dad’s ambition as a cautionary tale or in a gentler light?

I feel an amazing amount of empathy for him. After my dad got here, there was a whole side of his life that he never got to develop. He didn’t have hobbies—or friends, really. Think about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: he was in work mode. I have the privilege of climbing higher on that pyramid than he did. I could say, “Boy, I wish he spent more time with us,” but without him, I wouldn’t be where I am.

MORE: Canadian doctors say birth tourism is on the rise. It could hurt the health care system.

The time you weren’t spending with your dad, you spent boxing. You were actually training to go pro as a teen. How much energy were you spending in the gym?

A comical amount. From Grade 8 on, I’d wake up every morning at 4:30, run up to 13 miles, then skip and lift weights at the gym near my high school. I’d eat breakfast during class. At night: sparring and suitcase jumps. I only ever missed a day.

But, Peter: why?

Working hard was the first thing I identified that I could do better than anyone else. I had to be first in my class, then the best surgeon. That said, I’d be very concerned if I saw my kids behaving like I did.

Did they inherit your affinity for exercise, or are they just into Roblox and those pre-wrapped PB&J sandwiches I see on TikTok?

My daughter is 15 and loves volleyball, but she probably loves Taylor Swift more. My boys, though, are obsessed with trying to show me how strong they are. I want exercise to be fun for them, not an obligation.

On fun: do you have a favourite vice?

I love junk food. I wish I could say I was discerning, like, “there’s this one brand of carrot cake,” but I love all carrot cakes! But what do I need to be careful of? Online shopping. When the packages start showing up, my wife is like, “Okay, what are you numbing?” I’m out of control with Lego.

You also have a vegetable garden, which is more work than leisure, I guess. Any big produce success stories?

Truthfully, most of my effort is spent on figuring out ways to keep a certain squirrel from eating all my tomatoes. I hope I can do it without shooting him. My kids won’t let me, but believe me, I’m tempted.

…which brings us back to death. You talk quite often about the “marginal decade,” or the last decade of life, and work with your patients to create a health plan to make sure they can perform specific tasks in their twilight years. What’s on your bucket list? Seeing a mountain? Another Chris Hemsworth movie?

I always want to be able to put on my underwear, shorts and pants while standing. I want to be able to pick up a child—say, a 30-pound grandchild—off the floor. I recently worked out with Arnold Schwarzenegger at Gold’s Gym. He’s 76 years old and he’s going to pump iron for the rest of his life. That’s important to me, too.

And travel?

I’m making sure I don’t leave things till the end. I also want to be able to carry my own luggage. Even if there’s an escalator, I’d rather take the stairs.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.