Robin Williams: The stigma of suicide and banishing the ‘demons’

Robin Williams’s death came as a surprise—and that’s an indictment of our blindness to depression and its potential consequences

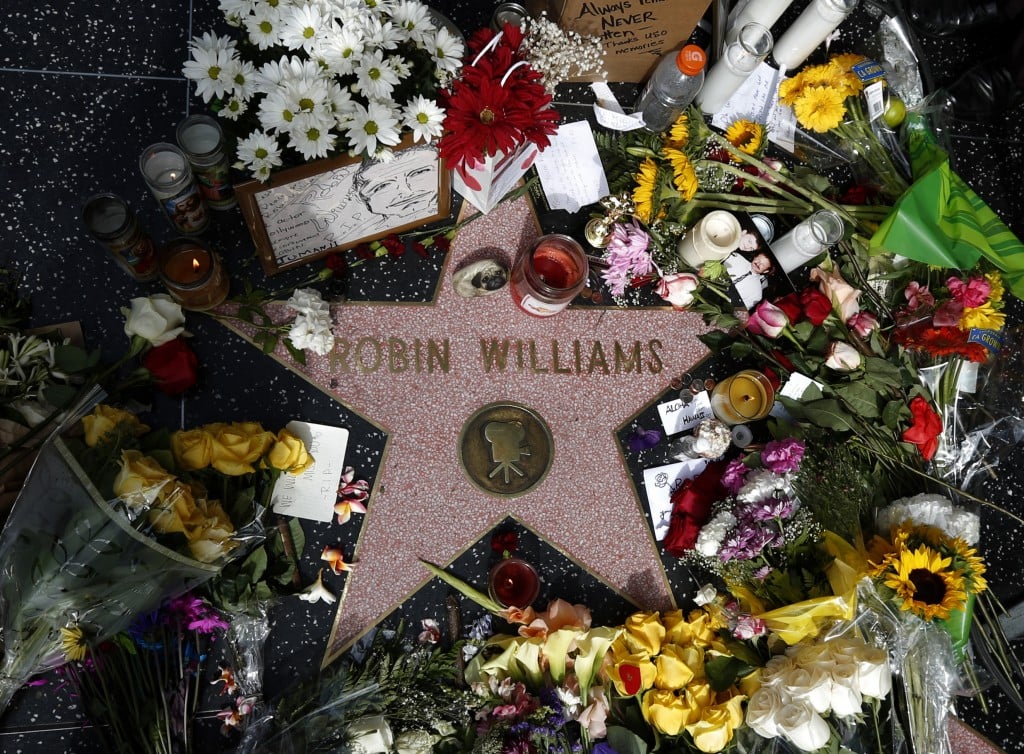

REUTERS/Lucy Nicholson

Share

True to the grip beloved celebrities have on the cultural imagination, the 24 hours following Robin Williams’s tragic death thrust more attention on suicide awareness than decades of public service announcements have ever accomplished. CBC’s The National convened a medical panel to discuss depression, substance abuse and suicide. Mental health organizations, among them Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, posted blogs offering advice and phone numbers for people thinking about ending their lives. Williams was marshalled as a reminder that, despite media focus on suicide in teenagers and young adults, suicide risk rises as people grow older, with men four times more likely than women to kill themselves, even though women are twice as likely to receive a medical diagnosis of depression. Forbes magazine even turned the tragedy into a trend story: “Robin Williams casts spotlight on the growing risk of suicides among Baby Boomers.”

But for all of the “awareness” amplified in the echo chamber of social media, a broader cultural uncertainty, even ignorance, about suicide was also evident. We’ve seen stigma associated with suicide reduced since Kurt Cobain took his life 20 years ago; then, the fact the musician struggled with depression wasn’t a salient detail. There’s been a pendulum swing, too, from the traditional guidelines issued by psychiatric and public health organizations that long kept suicide in the shadows. The Canadian Psychiatric Association’s rules for journalists, for instance, still includes a list of topics to be “avoided” when reporting on suicide: front-page coverage; details concerning the method; the word “suicide” in the headline; photos of the deceased; details concerning the method; admiration of the deceased; the idea that suicide is unexplainable; simplistic reasons for the suicide; approval of the suicide. The rationale, clearly established pre-Internet, is that broadcasting news of suicide glamourizes it and may lead to copy-cat behaviour—known as suicide “contagion.”

Yet the vocabulary for discussing suicide remains oblique, evident in the frequent use of euphemisms such as “suddenly died” or “unexpectedly died” in death notices, as well as the reliance on the word “demons” to explain mental illness.

We’re still figuring out how to have the conversation, evident when the Academy of Motion Picture of Arts and Science came under fire for a tweet it posted after Williams’s death. It featured an image from the animated film Aladdin, in which the actor starred as the voice of Genie, with the mawkish message: “Genie, you’re free.” Clearly, it struck a chord: It was retweeted more than 168,000 times and seen by more than 70 million. Suicide awareness advocates criticized the academy for romanticizing the act: “Suicide should never be presented as an option,” Christine Moutier, chief medical officer at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, told the Washington Post: “That’s a formula for potential contagion.”

More than 38,000 Americans and 3,700 Canadians die annually of suicide, more than perish in car accidents in each country, indicating that suicide is a well-known “option.” Yet, even expressing anger toward it is considered verboten, seen when the actor Todd Bridges took to Twitter to accuse Williams of committing “a very selfish act.” (He later apologized, saying the tweet was in reaction to a friend’s recent suicide.) Bridges was blasted for being insensitive and out-of-date in suggesting suicide is a decision actively made. It’s not, as a widely circulated essay by the Suicide Project explains: “Suicide is not chosen; it happens when pain exceeds resources for coping with pain.”

But that shouldn’t preclude discussion of the fact that suicide is a tsunami let loose on those left behind, as response to Williams’s death makes clear. It renders family and friends overwhelmed with grief and guilt that they could have prevented the death; it’s not uncommon to feel anger, as well, toward the person who died—anger that needs to be aired. Children are burdened, as well, with the legacy of a suicide narrative, seen writ large in Ernest Hemingway’s family. Not speaking openly about suicide’s effect can be toxic, as Mariel Hemingway, Ernest’s granddaughter, told Salon last year. The actress and filmmaker discussed her own struggle with depression and the fact neither suicide nor depression was discussed in her home, despite a harrowing history: Seven family members took their lives, including her grandfather, her sister, Margaux, and her uncle Gregory.

The Hemingways and, now, Williams, serve as proof, as if more were needed, that wealth, professional success and access to treatment doesn’t always provide protection. That can be daunting for those struggling with mental illness, a point eloquently made by Molly Pohlig on Slate this week. Pohlig, who suffers from clinical depression, shared how difficult it was for her to see Williams succumb to the same disease. She also detonated myths circulating in online comments, including the supposition that, had Williams known how many people loved him, he never would have killed himself. It’s very likely the comedian did know people loved him, she wrote—but it doesn’t matter: “At my lowest, love cannot save me. Hope, prayers, daily affirmations—none of these can save me. Therapy and medicine are what matter, and those don’t always work, either.”

That Williams’s death came as such a surprise is probably the greatest indictment of cultural blindness to depression’s potential consequences. For decades, he’d discussed suffering from bipolar disorder, severe depression and addiction to alcohol and drugs. He’d mined the topic of his substance abuse so long for laughs that its gravity had vaporized; still, a fragility behind his manic facade was evident to anyone paying attention. In a 2010 interview with the Guardian publicizing World’s Greatest Dad, a movie whose references to suicide are now haunting, Williams was asked what he was afraid of: “Everything,” he said. “It’s just a general all-round arggghhh. It’s fearfulness and anxiety.” He was also public about seeking help, as recently as last month, though what his treatment regimen was is not publicly known. The fact that the actor was newly out of rehab has also led to discussion about how that period can be the most vulnerable time for many. It’s information that, sadly, couldn’t save Robin Williams. If we can figure out how to talk candidly about suicide long after the spotlight inevitably dims on his sad last days, it might save someone else.

Remember the legacy of Robin Williams with a free digital edition of our special commemorative issue, available for download on your iPad. For subscribers, check the newsstand in your Maclean’s app. For new readers, follow this link to download the Maclean’s iPad app in the iTunes Store. You can also find it at Next Issue Canada.

Remember the legacy of Robin Williams with a free digital edition of our special commemorative issue, available for download on your iPad. For subscribers, check the newsstand in your Maclean’s app. For new readers, follow this link to download the Maclean’s iPad app in the iTunes Store. You can also find it at Next Issue Canada.