Why we can’t shake our carbon-emitting habits, even as the world burns

If we know the situation is dire, why is it so hard to change our habits? Oh, 37 different reasons.

People engage in ‘moral licensing,’ such as

rationalizing flying because they recycle

(iStock/Nadezhda1906)

Share

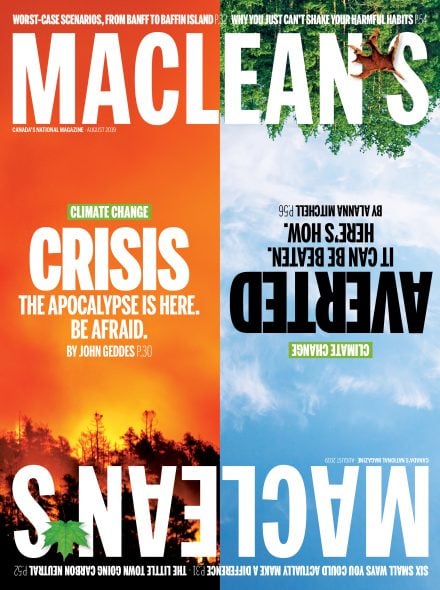

This article is part of a special climate change issue in advance of the federal election. This collection of stories offers a comprehensive look at where Canada currently stands, what could be done to address the issue and what the consequences might be if this country continues with half measures. Learn more about why we’re doing this.

Given the growing awareness of the climate catastrophe speeding toward us, one might think humanity might be doing more to curb our carbon-emitting behaviours. But even for the most worried, a host of latent psychological factors can paralyze us, turning people into climate couch potatoes.

There are, in fact, 37 specific mental barriers that limit our ability to react to climate change, according to University of Victoria psychology professor Robert Gifford. These barriers—Gifford calls them “dragons”—fall into seven broad categories: limited cognition, ideologies, comparison with others, sunk costs, discredence, perceived risks and limited behaviour. When he published a 2011 article in American Psychologist that identified the first 29 of these dragons, the article went viral and became the publication’s most-read piece in its history.

Among the many specific barriers identified by Gifford are outright denial (for example, take Donald Trump, who tweeted climate change is a Chinese hoax); tokenism (i.e., I recycle, so I’m doing my bit) and technosalvation, or the belief we will build machines to save us so we can all just keep doing what we’re doing.

READ MORE: The climate crisis: These are Canada’s worst-case scenarios

Then there’s the limit of our own “ancient brains.” Our minds, explains Gifford, have evolved little since humans developed agriculture about 12,000 years ago. We are thus hard-wired to respond to immediate, visible dangers rather than future, less obvious ones. That inherent trait makes it difficult for us to grasp and deal with the more distant, complex and somewhat abstract nature of global warming.

Gifford now uses his research to help governments and environmental organizations shape more effective programs to fight climate change. This past June, for example, Gifford met with a number of deputy and assistant deputy ministers with Environment and Climate Change Canada in Ottawa.

“There have been some well-intentioned policies and interventions in the past that simply didn’t work very well,” opines Gifford, explaining that such campaigns often don’t factor in the mental barriers to action in the first place, and therefore don’t create effective messaging to overcome them.

He recalls the $45-million flop that was the One-Tonne Challenge program, launched by the Canadian federal government under the Liberals in 2004. Using comedian Rick Mercer in print and television advertising, the campaign encouraged Canadians to reduce their emissions by one tonne each year by such actions as taking public transit more, idling vehicles less and sealing homes with weather stripping.

While the government’s own evaluation of the program found it raised some awareness, says Gifford, the program generated little actual response. “Many people did not change their behaviour because they said they lacked information about how to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions,” he says, a clear example of the “Lack of Knowledge” dragon genus. They also perceived the challenge as too inconvenient or time-consuming (a species of Gifford’s “Conflicting Goals and Aspirations” dragon); they believed that their own participation would not make a difference to climate change (another dragon); and, adds Gifford, “they believe that they are already doing enough—a species of my ‘Tokenism’ dragon genus.”

RELATED: Yes, climate change can be beaten by 2050. Here’s how.

If Canadians are to help fight the climate crisis by changing their own lifestyles, knowing how to spot their own dragons is the first step to slaying them. At the University of British Columbia, there’s a class for that. In early June, Kim Biel and his long-time partner Denise Panchysyn sat in a UBC lecture room in Vancouver to take in a one-week extended learning course titled “Climate Change: Understanding and Overcoming Barriers to Action.” Taught by Seth Wynes, a Ph.D. candidate in the department of geography at the University of British Columbia, the course—part of UBC’s Ageless Pursuits continuing education program, and based on his own research—probed those mental barriers preventing many of us from tackling the issue.

Biel, 63, and Panchysyn, 66, have both contended with one of Gifford’s dragons—environmental numbness. The retired couple, well-read on global warming, are deeply concerned about its impact on the Earth. “Kim even went to see Anthropocene,” says Panchysyn, referring to the visually stunning, though disturbing, Canadian-made documentary depicting mankind’s re-engineering of Earth. “I wouldn’t go, though,” she adds. She veers away from television shows about climate change: “It’s just too depressing.”

According to Gifford’s findings, constant bombardment of news and information about the threats posed by climate change can ironically overwhelm a person’s impetus to do their bit to combat it. “We have both experienced some overload that results in paralysis in terms of, how do we act on this?” confesses Biel. Importantly for Biel and Panchysyn, Wynes’s class also suggested the most effective ways people can reduce their carbon footprints.

A former high school science teacher, Wynes began his research on climate change mitigation after experiencing difficulty answering students’ questions about the most effective ways to help combat it. These are tricky questions, says Wynes. “Some of [the solutions] involve sacrifices,” he explains. “They involve interactions with the rest of society . . . What are the cultural cues you get about being a vegetarian? How is eating meat related to perceptions about masculinity? There is so much intertwined in these questions that often make it difficult to adopt actions that could save the climate.”

READ MORE: Climate change is making wildfires in Canada bigger, hotter and more dangerous

In his own research, Wynes—who cited Gifford’s findings in class—found evidence of a “climate mitigation gap,” where education and government recommendations often miss the most effective actions Canadians and others can take.

For instance, he says, few governments say the most effective ways to reduce carbon footprints include having one less child, ceasing air travel, living car-free and eating a plant-based diet. Instead, much of the educational and government literature focuses on less effective measures, such as hanging clothes out to dry, or installing more efficient LED lighting in homes.

The reason for that, Wynes suggests, is a “foot-in-the-door” strategy. “Communicators emphasize easy-to-perform actions that get people started on environmental lifestyles, and hope that people adopt more important actions later. Unfortunately, with the scale of the climate problem, we don’t have time to focus on small changes anymore.”

Wynes’s research focuses on such questions as, “How do we motivate people to change?” We have, in fact, managed to motivate past improvements in areas strongly resistant to change; in Canada, we reduced the number of smokers, normalized the use of seat belts and made dumping garbage on roadsides and parklands abhorrent to all but a small percentage of reprobates. That’s why Canada’s deputy ministers handling environmental files wanted to consult Gifford to craft effective policies that a large segment of the population would actually be willing to implement. And, says Gifford, it’s why organizations like Greenpeace and the World Wildlife Fund have been increasingly leveraging the related expertise of psychologists to mould their campaigns and programs. It’s also important, adds Gifford, “that we test those policies and interventions as they are going along to make sure they are effective and remain acceptable.”

RELATED: What climate change would mean for Canada’s famous landmarks

One troubling finding in Wynes’s research is how misinformed people are when they engage in what psychologists call “moral licensing.” “We do this with dieting,” says Wynes, explaining the term. “We say, ‘I went for a jog, now I can eat cake.’ Some people do this with green behaviours: ‘I have recycled for a year, so therefore I can go on a vacation to Cuba.’ ”

Wynes has conducted as-yet unpublished research on how well people understand their own carbon footprints. For instance, how long would a person need to forgo eating foods packaged in plastics in order to offset the greenhouse-gas impact of eating meat? What he discovered is that “people are pretty terrible at making those trade-offs. Probably worse than they are about making similar decisions about their diets, for example.”

One area Wynes focused on was air travel, noting that travel is a particularly hard habit to rewire in people. The morning Wynes’s course started, Panchysyn was planning to book a flight from Vancouver to Calgary. She pondered, though, whether a train trip might be more environmentally friendly. It is significantly better, she learned in Wynes’s class. According to the website EcoPassenger—which calculates the CO₂ output of various trips by train, plane or automobile—a trip by train from Paris to Berlin, for instance, emits 26.1 kg of CO₂. The same trip by plane produces about 142.1 kg, roughly five times more. Once skeptical of buying carbon offsets to counter the impact of their travel bug, the couple are now considering them. “We wish that the signposts on how to act on these things were more obvious,” says Biel.

Laurie Gould, 71, a former teacher, also attended Wynes’s climate change course. “I have always been very concerned about minimizing my footprint on Earth. I went to the class because I felt what I was doing was minimal,” says Gould. Even with the advice of her daughter, a marine biologist, Gould still felt uncertain about how to best do her part for a healthier planet. “I had done the obvious things . . . I don’t use wax paper. I don’t use paper towels. I try to find environmentally friendly soaps. But I was stymied about my car.”

That car is her much-loved 2002 Honda Accord. Was it better for the planet if she traded it in for an electric or hybrid vehicle? The answer, she discovered in class and verified with her own research afterwards, is yes. She’s now planning to visit dealerships in Vancouver to test-drive electric and hybrid vehicles. “The incentives that the federal and B.C. government are offering certainly make the purchase more affordable right now,” said Gould in an email a few days after the course ended.

Since the course, she’s been busy busting a few more dragons. On the last day of class she had a GIC come due, and on the same day put that money into a sustainable fossil-fuel-free investment fund. And after learning from Wynes about the massive amount of greenhouse gases emitted by the beef industry, “last night I cooked up the last pound of ground beef in my freezer and plan to never cook beef again,” says Gould.

“That will be hard,” she says, “because my two grandsons love my meatballs. So I’m hoping to find a good recipe for ground turkey or chicken meatballs that they will like. I recognize that I’m able to do these things because I live a privileged, middle-class Canadian life. But I also realize that it is my comfortable kind of lifestyle that is responsible for much of the CO₂ emissions that are destroying our atmosphere.”

This article appears in print in the August 2019 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “The mental block.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.