How do you like them genetically engineered, non-browning apples?

The first non-browning apples created by B.C.’s Okanagan Specialty Fruits just got USDA approval—and not all apple growers will be happy

Nonbrowning Arctic® Granny, with slices cut out. Credit: Okanagan Specialty Fruits

Share

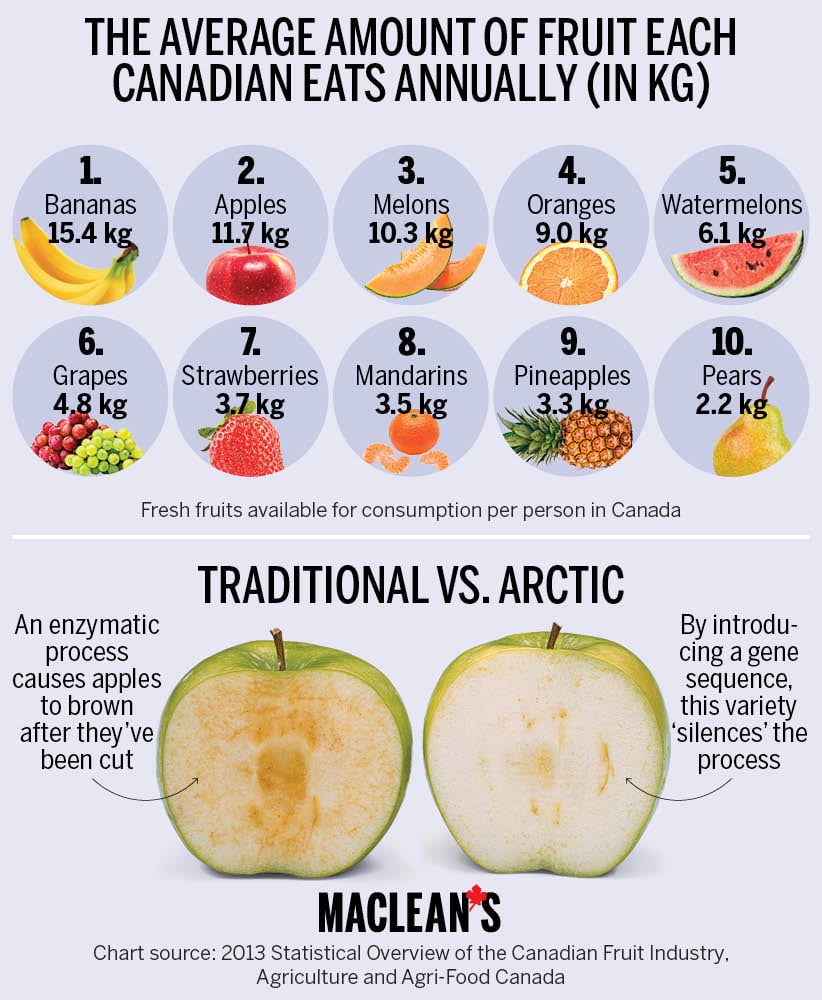

For a brief period about five years ago, there were fewer homegrown apples for sale on Canadian grocery-store shelves than there were melons. They’ve since edged back ahead of melons, but, with the exotic array of fruit available in the grocery aisle, Malus domestica remains second banana to, well, bananas. Apple sales have been stagnating.

Each Canadian ate an average of almost 12 kg of apples in 2013, adding up to around $200 million for apple farms, according to Agriculture Canada. But the domestic apple market has been moribund, and exports have decreased more than 50 per cent over the past decade, says a 2013 report for the Canadian Horticultural Council.

The problem may be one of aesthetics, some believe. Okanagan Specialty Fruits Inc., an agricultural biotech company, thinks its non-browning apples will open up a whole new market for packaged and pre-prepared foods. Its Arctic apples have been genetically engineered not to brown when sliced or bitten. The company, based in Summerland, B.C., has patented a way to “silence” the genes responsible for the enzymatic process that causes browning. It does this by adding a gene sequence into the cultivar’s DNA that disrupts the function of the genes responsible for that process.

“The history of apples, and any other fruit, for that matter, is a history of innovation and improvement,” says Neal Carter, founder and CEO. Apples have been selectively bred for thousands of years, for everything from taste to texture, he says.

The company had been waiting for a decision from the United States Department of Agriculture on the Arctic apples for five years. Approval for the firm’s Arctic Golden and Arctic Granny finally arrived last week. “Since it takes apple trees a number of years to produce significant amounts of fruit, it will likely be 2016 before any Arctic Granny or Arctic Golden apples are available for small test markets,” Okanagan Specialty Fruits said in a statement. A review is also under way by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and Health Canada, and Carter says that process is nearing its end.

The B.C. Fruit Growers’ Association and the Fédération des producteurs de pommes du Québec are opposed to the modified Malus domestica. Yet it’s not the science these groups fear.

Labelling of genetically modified products is voluntary in Canada, and they’re worried about confusion in the produce aisle. “We are most concerned about a backlash,” said Fred Steele, president of the B.C. association, in an interview before the USDA approval. In 1989, the U.S. news program 60 Minutes aired a story about the controversial ripening agent Alar used on apples, in which it was called “the most potent cancer-causing agent in our food supply.”

Reaction was swift and unforgiving. The apple market crashed and, while the manufacturer debated the science behind that claim, it voluntarily halted sales for food uses. “That affected our prices and our ability to hold market share for four or five years,” Steele says. “I’m not bent out of shape about what people want to do in the GMO marketplace,” says Steele. “I just don’t want it in our marketplace.”

Carter says the comparison with Alar is unfair and unrelated. “First and foremost, my family and I are apple growers,” he says. “The Arctic apples have been through a rigorous review and found to be safe. We’ve been very open and transparent about the product.”

Jim Brandle, CEO of the Vineland Research and Innovation Centre in Ontario, says perception is reality in the produce aisle. The not-for-profit Vineland centre itself is working on identifying the molecular markers in apples related to characteristics such as sweetness, disease susceptibility and texture. One researcher at Vineland was recently awarded by Genome Canada for a project that found a strand of DNA connected to what it describes as the sweet “red-apple” taste favoured by consumers, which is actually unrelated to the colour of the fruit. Although Vineland is not working on genetic engineering, gene sequencing is now routine, Brandle says.

The apple has about 57,000 genes—more than the 21,000-plus in the human genome. The complex genetics mean apple trees from seeds are unpredictable, so commercial orchards are propagated by cloning, usually by grafting a new stem from an existing tree onto rootstock. “Without human intervention, there would be essentially no edible apples growing in North America,” Carter says. Indeed, the crabapple is the only apple native to this continent.

There are now more than 7,500 varieties of apple, and one day’s pomme du jour is the next day’s kale chips. The McIntosh of yesteryear gave way to the Gala, and now the Honeycrisp is hot. “Gala is an apple that wasn’t around 20 years ago, and Honeycrisp, as well,” says Brandle. “But they’ll cycle out. People will get used to them and something new will come on the market.” New apple varieties are big business. Patented and trademarked by breeders, they can only be cultivated by licensed orchards. “It’s a new world,” says Brandle.

Genetically engineered products are not rare on grocery shelves in Canada. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency has approved modified papayas, tomatoes, corn, potatoes, soybeans and squash. Okanagan Specialty Fruits is working on non-browning Fuji and Gala apples, and research is underway at OSF on pears, peaches resistant to the plum-pox virus, and apples immune to fire blight, a bacterial disease that attacks trees.

Brandle says if Arctic apples get to fruit stands in Canada, the public will make the final decision. “How big it is, and how important it’s going to be, I think the marketplace will determine. People, they’re going to go for it or not.” Steele doesn’t think they will. “I don’t want to eat a cut apple that’s three days old anyway,” he says. “I’ll eat a fresh one.”