I help librarians handle book bans. Here’s why it’s getting worse.

“Book ban movements are shutting down important conversation, rather than encouraging diversity of thought and exposing kids to new lived experiences”

Share

In 1987, I became a school librarian at a middle school in Maple Ridge, B.C. By the early 2000s, I was president of the Canadian School Libraries, or CSL, and I later joined the Centre of Free Expression at Toronto Metropolitan University. I now work as the coordinator of the Teacher Librarianship program at UBC. Throughout my years as a librarian, I’ve seen several book ban attempts at school libraries. In 2009, I helped a teacher-librarian at a B.C. middle school deal with a parent demanding to remove books with sexual content, gay characters or profanity (including swear words or symbols representing them). That particular school had a policy that allowed parents to make decisions about which books were available in the school’s library. With the support of the CSL and the local teacher union, we managed to have the policy rescinded and the books in question were kept on the shelf.

Over the last year, there has been more misinformation than ever before spread on social media about what happens in libraries. People have accused school libraries in Canada of having books with child pornography and accused teacher-librarians of trying to indoctrinate children with LGBTQ+ ideology through books about gender identity and sexual orientation. It’s become easier for parents to rally around this misinformation and advocate for book bans. In 2022, the American Library Association reported an unprecedented 1,269 demands to censor library books—nearly double the previous year’s number.

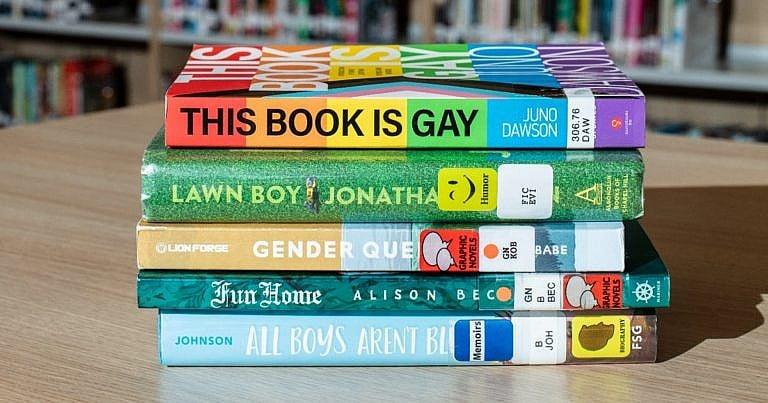

Though Canadian data is limited, I’ve noticed more parents asking librarians to justify books in their collections. Books discussing themes of sexual orientation and gender identity have come under fire—titles like the young adult novel All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson, a series of essays about growing up as a queer Black man. In the past few years, parents have asked B.C. librarians to remove Harry Potter books from their shelves because they believed the book’s reference to black magic was a negative racial stereotype. Other parents wanted to ban the Diary of a Wimpy Kid series because the book deals with bullying. Last year, parents complained to a B.C. library about Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator by Roald Dahl—it had scenes they thought were racist. Another parent complained about Emily’s Runaway Imagination by Beverly Cleary because one character mocks another’s English. There’s also been backlash directed at B.C. libraries for carrying Abigail Shrier’s book Irreversible Damage, about the rise in gender dysphoria and transgenderism in young women.

These books shouldn’t be stowed away because someone doesn’t like them or disagrees with topics they cover. Restricting access to books goes against our Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which upholds freedom of choice, expression and thought. I’m worried that book ban movements are shutting down important conversations, rather than encouraging diversity of thought and exposing kids to new experiences. Some might argue that banning one children’s book at one school does little to impact the greater discourse. But removing even one book from a library anywhere in the country can bring about other book bans elsewhere.

READ: Far-right religious groups protest my drag storytime events. Here’s why I won’t stop.

For the past two decades, I’ve been helping teacher librarians navigate book ban requests. If parents have a concern with a book, librarians ask them to fill out a “request for reconsideration form” to review the item. The result is often the same: the book stays on the shelf, and parents receive an explanation why. But that protocol isn’t always followed. Last year in the Durham School District, the book The Great Bear was removed from library shelves after the board said it received complaints about it from the local Indigenous community. When media outlets wrote about the incident, the board met and reinstated the book within weeks. I attended the board meeting on Zoom and sent questions as part of the CFLA Intellectual Freedom Committee’s concerns with how the district followed the process. After the book was returned to library shelves, I wrote an article saying that next time, the board should first ask parents to articulate their complaint and then be more critical as to whether or not the complaint is justified. The challenge is that districts themselves are businesses that cater to parents. One person criticizing a book shouldn’t be enough to have it removed—we don’t want to create a precedent for book banning that erodes debate and discussion in our libraries.

Unfortunately, it’s easier than ever to find like-minded people on the internet and organize hostile book-banning movements. There are a number of Facebook groups and websites, usually run by parents, that target libraries for carrying titles related to sexual orientation and gender identity. Tiffany Justice, who leads Moms for Liberty—an organization in Florida and Texas working to ban books on LGBTQ issues and by some minority authors—has said that Canadian moms have reached out to her to set up chapters. In my opinion, these groups stoke fear and misinformation, encouraging parents to join them to “protect” children.

In February, Action4Canada—a B.C. organization with chapters across the country and a strong online presence that promotes conservative ideals—demanded that libraries in B.C. and Ontario remove books discussing sexual orientation and gender identity, like Gender Queer by Maia Kobabe or The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison. They accused Chilliwack’s public school libraries of housing some books that depicted child pornography—a claim the RCMP investigated and found no basis for. To me, the organization’s emails read like an attempt to restrict books they don’t agree with rather than an earnest effort at protecting kids.

RELATED: The Big Idea: Defend Drag Shows

The dangerous alternative to Canada’s democratic book evaluation processes is a set of rigid regulations seen in the United States. In Louisiana, each time a librarian adds a new book to the school’s collection, they have to read it, write a report on its content and then send it to their district and state governments, who then determine whether or not the book is appropriate. They repeat this process with every book. In Texas, a state law stipulates that each book warrants another with an opposite point of view. For each book about climate change, for example, you need a book that tells you that climate change hasn’t been proven.

Our charter protects against laws like these. In what has become known as the Surrey Book Case of 2002, the Supreme Court ruled that a B.C. school board was wrong to ban three children’s books that favourably depicted same-sex marriages. The court determined that “tolerance is always age-appropriate” and parent complaints weren’t enough to warrant a ban. Children should be afforded the freedom of choice to read what they want, and it’s with that spirit we should approach conversations about the kinds of books we add to school libraries. People have the right to question books they deem offensive and voice their opinion about books they don’t like, but as the Supreme Court stated in 2002: “Persons are entitled to hold such beliefs as they choose, but their ability to act on them, whether in the private or public sphere, may be narrower.”

Defending books is a constant battle that we must take seriously. If you’re concerned about a book, you don’t have to read it. As a parent, you can decide your kids shouldn’t read it. But one person or group shouldn’t be allowed to decide what an entire community reads.

—As told to Alex Cyr