Coronavirus turns Easter, Passover and Ramadan into long-distance occasions

Religious leaders are finding creative ways to perform services and comfort congregants. But without the human touch, holy days just aren’t the same.

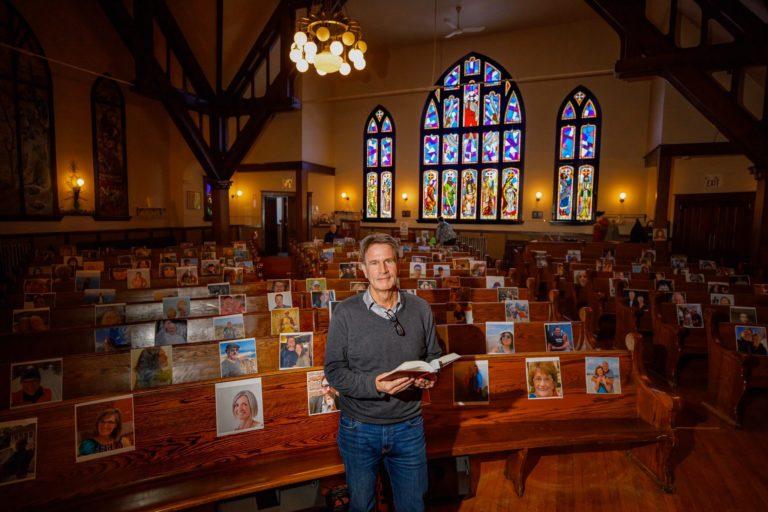

Rev. John Pentland speaks to a sea of pictures—his congregants—when he performs online services from Hillhurst United Church in Calgary. (Leah Hennel)

Share

The pews at Hillhurst United Church in Calgary, one of the city’s oldest buildings, have sat empty for more than two weeks. It’s an unusual sight for the 115-year-old edifice, which has only closed its doors once before: during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. More than a century later, the novel coronavirus has forced the historic church to shutter once again.

Determined to keep the presence of congregants alive, the church pasted large, colour photos of its smiling worshippers on its pews. Their faces are visible as Rev. John Pentland delivers his normally well-attended Friday sermon, now live-streamed online. Hillhurst, like many places of worship across Canada, has been forced to adapt to the new reality of social distancing and limits on large gatherings, while finding creative ways to stay connected to a community that needs reassurance and comfort more than ever.

“It’s really an odd thing to be a religious community and not to be able to be physically connected,” he says.

READ MORE: Quarantine nation: Inside the lockdown that will change Canada forever

The church is now preparing for its Easter Sunday mass, a major holiday that is undoubtedly bound to look and feel different for its hundreds of congregants and millions of Christians worldwide. It’s a difference that has been felt profoundly by members of the Jewish community this week as they celebrate Passover, and one that will be felt by Muslims who will observe Ramadan, starting in the last week of April—all of which dates that are normally marked by large, heartfelt gatherings with loved ones and neighbours.

The onset of these holidays has caused concern for political and community leaders, who are urging communities to observe the occasions at home. Public health officials in Manitoba stressed that “people should not let their guard down by gathering this year” for Easter and Passover. But it’s a message that has been embraced by religious leaders, too.

“We’re people of the flesh, we’re huggers, we’re hand-shakers, so it feels so odd to not have physical touch as part of our Easter experience,” Pentland says. But “the best way to be a good neighbour,” he adds, “is to stay home.”

Hillhurst will instead carry its programming online, live-streaming its Easter Sunday service—usually attended by 700 people from across the Calgary area—on the church’s website and Facebook Live, where Pentland will be delivering the service from his home.

Even communion will be done via the internet for the first time in the United church’s history, says director of programming Anne Yates-Laberge. Worshippers are encouraged to bring their pita, their bread, or their chip, alongside their grape juice, diet soda, or wine. “Whatever you want,” Yates-Laberge says. And prayers over worshippers’ communion will be part of the live-streamed program. Catholic churches, Yates-Laberge adds, have high standards for communion that include having a priest present to bless the body and blood of Jesus Christ, but others, like Hillhurst, will be able to make do with doing it remotely.

READ MORE: Taking confession in a time of coronavirus—one driver at a time

“We’ve had to adapt to this world, and say, ‘You know what? It’s more important to people that communion has happened, instead of us getting stuck on the blessing of this thing,’” Yates-Laberge says.

Elsewhere, Saint Joseph’s Oratory of Mount Royal in Montreal, the largest and one of the most historic Roman Catholic churches in the country, is also adapting to this new reality. Its Easter celebrations are typically attended by thousands, Rev. Claude Grou says, with nine masses held on Easter Sunday—seven in French, one in English and one in Spanish—all of which will now be live-streamed on the Oratory’s website. The church has also partnered with a local radio station to deliver daily mass at 8:30 a.m. every morning, a practice that will continue for the duration of the pandemic.

“To be forced by circumstances to celebrate without the community is really painful,” Grou reflects, adding there is profoundness sadness among worshippers, too. “It’s never the same as being in a community, gathering in a place together.” The Oratory has lived through most tragedies in modern human history: the two world wars, the Great Depression, and the Spanish flu. Still, never has an Easter Sunday mass been cancelled.

For Al Rashid Mosque, Canada’s oldest in Edmonton, preparations are taking place to move the place of worship—and with it the holy month of Ramadan—online. “This means a very different Ramadan for most of the community,” Noor Al-Henedy, the mosque’s spokesperson, says. Al Rashid will be cancelling their daily Iftars (the breaking of the fast) and Suhoors (meals consumed before sunrise).

They will be also cancelling physical Taraweeh prayers, which take place every night after Iftar and are so well-attended that space inside the mosque quickly fills up, leaving some to pray outside. These prayers will instead be led by imams online, Al-Henedy says, where worshippers can follow in real time from their homes. It’s a difficult transition for a month that is heavily reliant on family gatherings and connection.

Vigilance has also prevailed members of the Jewish community observing passover. Toronto’s UJA Jewish Federation, which represents around 200,000 Jewish people in the Greater Toronto Area, has issued directives written by doctors within the community that discourage public gatherings, both large and small, and restrict attendance of seders—Passover dinners—to only members of one’s household.

“Across the spectrum, you see a pretty strong and consistent message that people should be staying where they live and they should not be gathering for any reason,” Steve McDonald, a UJA member, says. “This is a time to put protection of life above all else.”

Passover rituals include the retelling of stories about the Exodus and the path to freedom and liberation of the Jewish people from ancient Egypt—the themes of which continue to resonate today, McDonald says. “As Jews, we’ve been celebrating Passover for thousands of years, in good times and in terrible times,” he says. Observing Passover this year, he adds, serves as a reminder of the responsibility to take care of people who are not yet free, whether they’re struggling with poverty or other terrible circumstances.

It is why Toronto’s UJA has shifted its efforts to delivering around 2,000 Passover food boxes to households in need, McDonald says. They’ve also launched a telephone tree, with more than 1,000 volunteers, to reach out by phone to the elderly in the community who may need groceries, a helping hand, or just someone to talk to.

“We have identified some people that are in very dire situations,” McDonald says. He adds that people recognize this is “a once-in-a-century challenge,” and the unifying spirit of Passover has been felt instead by people doing their part to give back to their community.

Still, the new reality of the coronavirus and the challenges it has brought are also profoundly felt. “We’ve said it’s the lengthiest Lent,” Pentland at Hillhurst Church says. “We’re really living the path of reflection, inner wondering, and we’re experiencing what it’s like to see people suffer and die, and the reality of the mortality of our individual and collective lives.”

MORE ABOUT CORONAVIRUS:

- The economy is in a Corona-coma, and not even Statistics Canada can tell us when we’ll recover

- Coronavirus won’t hit Alberta as hard as others. But its economic wallop will be brutal.

- Alberta’s coronavirus projections: Radically ramping up ICU capacity

- How to help your family navigate the coronavirus ‘infodemic’ on WhatsApp