‘He’s turned into one of Canada’s most infamous antique thieves’

From 2014: How the country’s most daring antique thief amassed a fortune by thinking small and slow

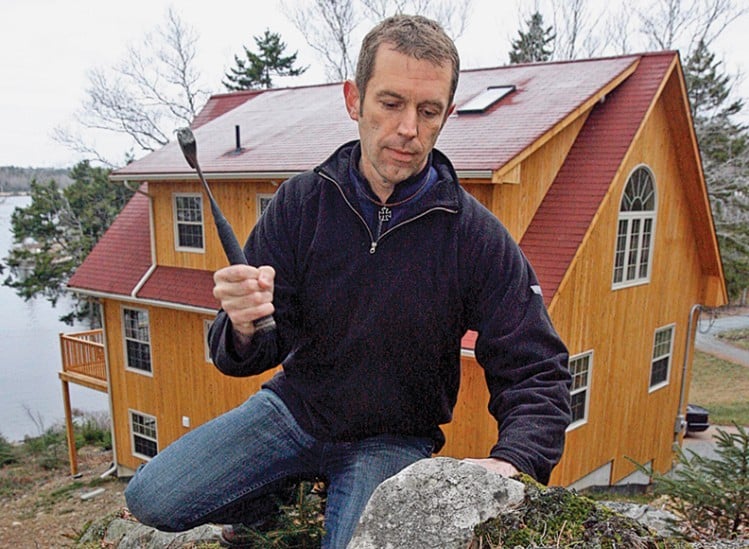

Tim Krochak / Halifax Chronicle Herald

Share

Update: John Mark Tillmann was granted full paroled in July, 2016, and told to stay away from libraries, museums and his former neighbours

On the outskirts of Murray Harbour, P.E.I., Preston Robertson gave tours of the Log Cabin Museum he had built by harvesting trees from his own property and stripping the wood with his sons. He worried about the province losing artifacts from its past, so he purchased antiques from flea markets and auctions and created a private collection representing rural life in P.E.I.

The museum opened in 1973, the same year the province celebrated its 100th year in Confederation. Robertson worked on his farm during the day, and when someone would stop by his museum, he’d wander over to give a tour. There was a horse-drawn buggy built in Charlottetown in 1888, farm equipment from the 1940s, and a 1905 Edison phonograph Robertson would crank up for visitors. As decades went by, the price of admission never climbed above $2.50.

On July 26, 2008, Robertson left his property for a party celebrating his grandson’s wedding. When he came back, he noticed that a set of four Nova Scotia pressed glass goblets, which were family heirlooms, along with several antique crocks, were gone. “He trusted people and felt betrayed when he found these items were missing,” says his daughter, Mada Coles.

Robertson had been the victim of theft before. On a shelf, a sign read: “A nice little saw hung here for 28 years until someone liked it enough to take it.” He created new signs for where the goblets and crocks once stood. He never called police to report the thefts.

A few years later, Robertson suffered a stroke. The museum closed and most of the items were auctioned off to pay for his care. He died in June 2012, at age 95.

Then, last October, Kaye MacLean, Robertson’s eldest daughter, received an unexpected phone call from the RCMP. They had found the stolen goblets and crocks near Halifax. And there was more. RCMP also had an antique Pictou tobacco canister they believed belonged to her father. She started to cry. “Dad was so hurt when that stuff was taken,” she says. “We never thought we would hear about those items that were stolen. Ever.”

As for the missing saw, there were two that fit the description, all stashed inside a lakefront home in Fall River, N.S., belonging to a 52-year-old ex-convict named John Mark Tillmann.

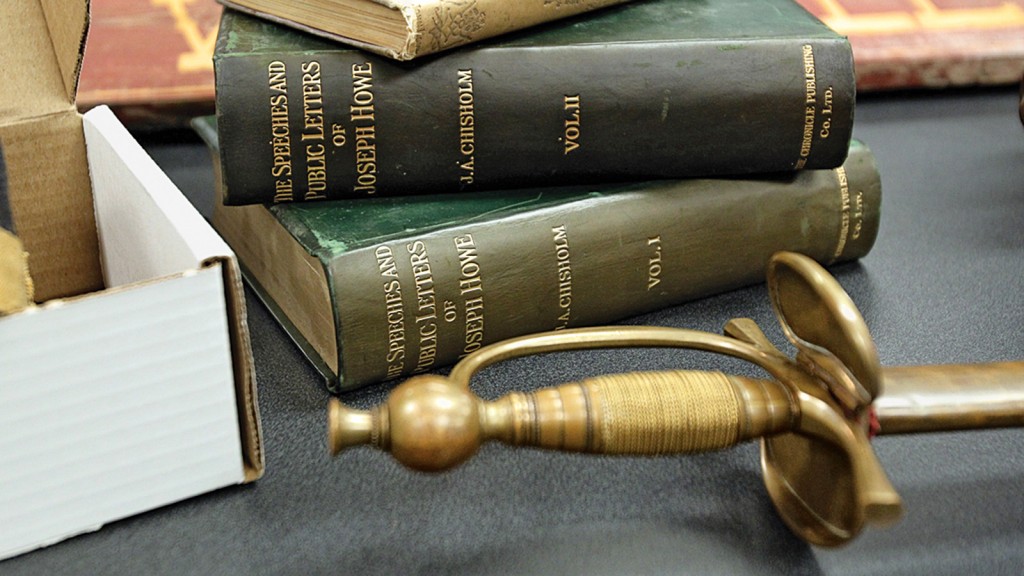

Tillmann made a career dealing in purloined antiques both big and small. He stole a letter once slated for delivery on the S.S. Titanic, but which missed the ill-fated trip. He had a letter written by George Washington—before he became president—commissioning a man, Moses Child, to spy in Canada. There was a letter from Victor Hugo, author of Les Misérables, asking a Nova Scotia family to look after his daughter. Artwork hung on Tillmann’s walls, including an 1819 painting of Nova Scotia’s Province House, which had previously hung in the provincial legislative library until it vanished around 1999. Tillmann’s bookshelf also once housed a first edition copy of On the Origin of Species by Charles Darwin, stolen from a locked glass cabinet at the Mount Saint Vincent University library, which he sold for $31,000.

“It was obvious that Tillmann spent a tremendous amount of energy devoting his life to getting his hands on as many valuable goods as possible,” says Nova Scotia Crown attorney Mark Heerema. “I’ve never experienced a file in which there was such a massive warehousing of antiquities.”

Unlike the elaborate art heists of Hollywood movies, targeting the rarest and most expensive artifacts, Tillmann’s thefts tended instead to be less extravagant and unusual in choice: a lemon squeezer, a nutmeg grinder, a brass telescope, a vintage wooden hockey table, a door, an Austrian water pitcher, a water pump, a steam engine, a geometric rug, a wooden apple barrel, a set of old wooden skis, and an old stove. His regular targets were museums, provincial and university archives, small-town antique shops, general stores and, in some instances, the very people he sold artifacts to. “The whole antique community in Atlantic Canada has been affected by this guy,” says Const. Darryl Morgan, an investigator on the case with the RCMP. “He’s turned into one of Canada’s most infamous antique thieves.”

Just as remarkably, Tillmann flew under the radar as an antique bandit for more than 20 years despite his frequent brushes with the law. Over the previous 25 years, he had amassed more than a dozen convictions on charges ranging from indecent telephone calls to assault with a weapon. In 2009, he was sentenced to two years in prison for threatening, assaulting and extorting money from an ex-girlfriend. There were dozens more charges either dismissed or withdrawn, including attempted murder of his elderly mother, failing to provide her with the necessities of life and assault with a weapon—in this case a pencil. “Some of the offences he was picked up for were shoplifting offences, like gummy bears or bottles of water,” Morgan says. “This guy was a kleptomaniac and a thief, in addition to the fact that he was a collector.”

Tillmann amassed a small fortune until a traffic stop in the summer of 2012 turned up a letter written in 1758 by British general James Wolfe—one year before he won the Battle of Quebec. Months later, an embittered ex-girlfriend came to police with a video Tillmann shot in 2011, in which he gives a self-narrated tour of his luxury home. In his garage he shows off a Porsche 911 and a Massey-Harris tractor. Then, inside his home, the camera zooms in on an 1891 painting of a barque by W.H. Yorke, estimated to be worth between $30,000 and $40,000. Sitting casually by his fireplace is a full suit of armour.

“It wasn’t like a hoarding. He had it on display,” Morgan says. “He was kind of a curator of his own little museum—in a little twisted way.”

On a snowy early morning in January 2013, police descended on Tillmann’s property with a search warrant and arrested him for possession of stolen property. Inside, they discovered that many items had labels saying what each artifact was worth. “The prices he was affixing to these things were the prices listed by the owners when he stole them,” Morgan says. In the kitchen, even though Tillmann doesn’t drink, were about a hundred bottles of expensive wine.

Morgan walked through the home with a guidebook containing phone numbers of local antique stores. “I called them up and said, ‘At any point in your lives, did anything get stolen from your shop?’ And they’d say, ‘Fifteen years ago, and this is what it was and it really bothered me,’ ” Morgan says. “I walked around the house and—boom—there it was. It was crazy.”

Last September, Tillmann pleaded guilty to 40 charges, including theft and fraud. Police confiscated more than 7,000 items. “He was very proud of the type of activities he was engaged in. It was more of a lifestyle,” says Const. Hector Lloyd, the lead RCMP investigator. “Everything about his lifestyle is completely corrupt.”

The RCMP is now tasked with finding the owners of each of the several thousand items, which, for now, are stored inside a secretly located, temperature-controlled vault in the Halifax area. The RCMP haven’t released a full list of the items, because they want to avoid illegitimate claims. Instead, they have enlisted the help of Tillmann himself, who is currently serving a nine-year prison sentence.

“I don’t want to be cast as a villain,” Tillmann says from Nova Scotia’s Springhill Institution, a medium-security prison. “There was no violence used at all.” In multiple interviews over the course of four months, he opened up about his reasons for stealing, the tactics he employed and his new life in prison. The conversations reveal a glimpse into the psyche of a highly unusual thief who lived a life of luxury by preying on trusting, small-town antique lovers. Posing as a buyer and a seller, he slowly built a fortune with relative ease—until he lost it all. If he could go back in time, avoid prison but never possess the rare antiques he amassed, would he? “There’s a very good question,” he says, “I’d have to think about that. I’m not sure.”

At Country Barn Antiques in Port Williams, N.S., the motto is “Browsers welcome, buyers adored.” Ken Bezanson bought the four-storey 1860s post-and-beam barn 31 years ago and started a shop selling everything from fine china to pine furniture. A decade later, he opened Borden House Antiques, which briefly had a suit of armour—a prop from the movie The Conclave—available to purchase for $1,500. That is, until it was stolen several years ago while his employee was distracted by what seemed to be a prospective customer. “The armour only makes noise when you’re wearing it,” Bezanson says, explaining that another person wandering through the store could easily steal the suit in pieces. “You just carry the breastplate down, carry the leggings down, and carry the arms down. You can do that in five minutes.”

Bezanson wasn’t there that day, but he never suspected Tillmann, someone who, over the course of 15 years, occasionally dropped by the shop to buy or sell items. “He could pass himself off as a scholarly type,” says Bezanson. “He was sophisticated, wore designer labels. I called him ‘Mr. GQ.’ ”

Tillmann typically used younger women as his accomplices, but his first partner-in-crime 20 years ago, he says, was his mother, Noreen Gregory. “Being a little old lady, she was trustworthy,” Tillmann says. “My mother would take [shopkeepers] into another room and they’d be so busy engaged in conversation that I could have walked out with probably whatever I wanted.” He’d never take more than one or two items at a time, to avoid suspicion. After a circuit of stealing from antique shops in the Halifax region, the two branched out with road trips to Cape Breton, expanding farther into P.E.I. and New Brunswick and travelling as far west as Cornwall, Ont. “I wouldn’t discriminate on any grounds, if it was a small or large shop, this section of town or another,” he says. “This was strictly business, as cold as that may sound.”

Speaking over the phone, Tillmann is polite and well-spoken, typically opening the dozen half-hour interviews he gave with chit-chat about the weather. He speaks candidly about selective heists, boasts about the beautiful women once in his company, and seems eager to see his story gets national attention. He talks about his knack for making items disappear from store shelves in his younger days—earning him the nickname “Houdini” from friends—and his love of studying history in school.

“The guy is a genius,” says his sister, Joy Tillman. “That’s the way he’s always been ever since he was a child. He didn’t have to work too hard in school, but had great marks.”

Tillmann studied at Mount Saint Vincent University, where he became especially fascinated with genealogy. He altered his surname from Tillman to Tillmann, in keeping with his German heritage—and reflecting a troubling obsession with the darkest era of that country’s history that would only fully come to light later in court.

Tillmann’s fascination with antiques stems from this love of history. “Say I’m holding a hand-forged tool that’s 200 years old,” he says. “It’s like a connection to the far forgotten past.” He started going to antique shops, but when he found he couldn’t afford certain items, he turned to theft.

Tillmann stole because he could. Because he was good at it. Because he never wanted to work for anyone else. Because he wanted to be a small part of history by having these items in his possession. Holding them. Organizing them. Selling them. At first it was about the antiquities, then it became a business. Business was good.

Police traced his travels to Russia, where Tillmann says he went “relic hunting.” He later returned to Nova Scotia and, in November 2001, incorporated his own business, Prussia Import and Export Inc. “I had designs of using the company as a front, to clean some of the money because, at this point, we were starting to accumulate a lot,” he says.

His heists also became more daring. To steal a painting that hung in Nova Scotia’s legislative library, Tillmann says he and an accomplice dressed up as maintenance workers carrying tools. They simply grabbed the painting right off the wall. “They didn’t notice it right away because they didn’t think we were doing anything wrong,” he says. “Nothing high-tech.”

To access the Dalhousie archives vault, Tillmann says he obtained a key and had a copy made, then hid in a washroom stall as security made the rounds before closing. He had an entire night to choose which rare papers to stuff into backpacks. He stole thousands of documents from the archives, including a letter from Victor Hugo to a Mr. Spencer with regards to compensation for Hugo’s daughter, Adèle, staying with the family as she pursued a British officer romantically. Oftentimes, the stolen items were never reported as missing and no one suspected Tillmann of being one of Canada’s most prolific art thieves. “He came in as a researcher,” says Michael Moosberger, the chief archivist at Dalhousie. Tillmann befriended Moosberger’s predecessor, the late Charles Armour, and came in on a regular basis to help with historical research on Nova Scotia shipping. Tillmann got to know the archives well and could easily sneak away with items. “I couldn’t even say when these things were stolen,” Moosberger adds. “Our collection is over seven kilometres long . . . in file folders where you have hundreds of textual materials. There’s no way to identify that two or three were missing.”

As the years went by, Tillmann also posed as a regular antique dealer who had fallen into good fortune by owning and operating a small gold mine on his Fall River property. The Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources has no record of there ever being a gold mine in that area, but Tillmann still managed to convince others of this gold-prospecting hobby.

“We called him ‘gold digger,’ ” says one of his regular buyers, “but he was very frugal. His house would freeze because he wouldn’t turn the heat on. He had no cellphone. He wouldn’t have cable.”

The buyer, who spoke on the condition his name not be used, says they first met around 2000 when Tillmann came to inquire about a used car. Over the years, he purchased from Tillmann a historic document about a meeting to discuss a potential sale of the Bluenose, before the Canadian schooner became iconic for its racing glory. “I bought stuff from John like I bought stuff from other dealers,” the buyer says. “I don’t understand how these places never made a report that they were stolen.” In fact, some stolen items were on full display when the Chronicle Herald published a profile of Tillmann’s home in 2008.

Being locked inside Springhill Institution has in no way diminished Tillmann’s ego. He says he detects admiration from fellow inmates, signs the occasional autograph and fancies a future with book and movie deals. “Yes, it is breaking the law. I’m reasonable enough to understand that you can’t be allowed to do that and get away with it,” Tillmann says. “The positive comments make me feel like it won’t be held against me forever.”

Tillmann refuses to reveal the names of his accomplices, unless they have since died. His mother passed away in 2009. Years later, on her online death notice, Tillmann wrote: “I will forever remember our ‘missions’ together, the challenge of adversity, the satisfaction of success and us taking on the world. We started with nothing, yet went so far as a team.”

The note ended: “Your heart was always good, Mom, and I know that you always loved me, your very difficult boy.”

Taking the off-ramp from Highway 118 into Fall River on July 18, 2012, Const. Kristen Bradley turned left onto Perrin Drive and immediately noticed a black BMW. He knew it belonged to Tillmann, who that May was sentenced to house arrest for defrauding a local auto shop with a forged cheque to pay for car repairs. Tillmann was allowed out that day at 1 p.m. for a few hours to run errands, and Bradley was en route to conduct a regular compliance check. He looked down at his clock, which read 12:52 p.m.—eight minutes too early.

Bradley pulled Tillmann over and arrested him for breach of house arrest. With Tillmann in the back of the squad car, Bradley returned to look at the BMW. “Right on his front seat is a cheque for $1,526,” Bradley says. Also in the same see-through plastic sleeve was a letter, browned from age with calligraphy-style writing. He looked closer. It was dated May 19, 1758, and signed by James Wolfe. “I thought: ‘There’s something wrong here.’ ”

Even then, police didn’t suspect Tillmann was a massive antique thief, but he was unable to prove how he came to possess such a rare letter. Police spent months searching for the rightful owner, until Karen Smith, head of special collections at Dalhousie University, came in and immediately confirmed the letter belonged to the university. “It’s that old cliché: You never know what’s going to happen at a traffic stop,” Bradley says.

At the bail hearing, the Crown showed Tillmann’s home video tour, complete with rare artifacts, as well as Nazi paraphernalia. A swastika flag hung over the railing and a framed photo of Adolf Hitler hung on the wall.

After two bail hearings, police found the letter from general George Washington at the home of Tillmann’s son, Kyle. The 23-year-old was charged with two counts of possession of stolen property and single counts of theft, perjury and obstruction of justice. (Multiple attempts to reach Tillmann’s son for comment were unsuccessful.)

Upon hearing of his son’s arrest, Tillmann says he started working on his plea bargain so the Crown would withdraw all charges against Kyle. Tillmann agreed to forfeit his 1.6-hectare Fall River property, two luxury cars, his $300,000 bank account and all the antiques. “Basically, the Crown seized everything he owned,” says his lawyer, Mark Bailey. “He really doesn’t have anything left.”

David Miller was 100 years old when he needed help restoring an old, red wooden chair. It had little monetary value, but it was an important family heirloom. Tillmann, using a pseudonym, offered to help. He took the chair home, but never brought it back. Police found it on display in his bedroom.

Shortly before Miller died at the age of 102 last summer, he saw his precious chair again. It was the first item of many that RCMP returned to their proper homes. Their task now is to find the rightful owners of the remaining stolen goods, including those Tillmann sold long ago.

In early January 2013, with the help of U.S. Homeland Security, authorities tracked down the copy of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, which had traded hands several times since being sold at a Sotheby’s auction by a Canadian who bought it from Tillmann. “I thought it was gone,” says Tanja Harrison, a librarian at Mount Saint Vincent University library. Upon hearing that the rare book had been retrieved, she said, “I was in disbelief—and really happy.” At the other end of the chain, however, are those who bought items in good faith and must now give them up. Earlier this year, a Nova Scotia book collector had to relinquish four illustrations by John James Audubon that Tillmann once stole.

Today, Tillmann passes his time in prison going to the gym or reading. “I trade a lot in here. I’m sort of a little jailhouse merchant,” he says. “Sugar and coffee become currency in here. I don’t eat sugar, nor do I drink coffee, so I trade all that for extra food—extra bananas, extra milk.” As part of his rehabilitation, he wants to tutor other inmates and find odd jobs around prison.

He has one particular position in mind: “I hope to work in the library.”