How to solve the food waste problem

Billions of dollars worth of good food is thrown away each year. Now some businesses and cities are saying no.

Share

At the Root Cellar, Victoria’s busy green grocer, the fresh produce is in perpetual motion—turned, trimmed, culled and completely refreshed by an army of workers twice each day. Co-owner Daisy Orser says her nearly 100 employees, whether they’re stocking clerks or cashiers, are all trained to cull produce that’s not perfect. But you won’t find much of it in the waste bin, because the company has several systems in place to make sure that less than one per cent of the food they buy hits the compost.

It’s labour-intensive but profitable, says Orser. Ripe or scarred items go first to the discount table or to feed hungry people at the Rainbow Kitchen and the University of Victoria’s student-run Community Cabbage, then to a green bin, along with carrot tops and corn husks that shoppers leave behind, for local farmers to collect to feed chickens and pigs. Excess berries go to Wild Arc, a wild animal rescue and rehabilitation centre. Composting is a last resort. “Our consumer in Victoria is an anomaly,” admits Orser, who counts 200 local farmers and food producers among her suppliers.

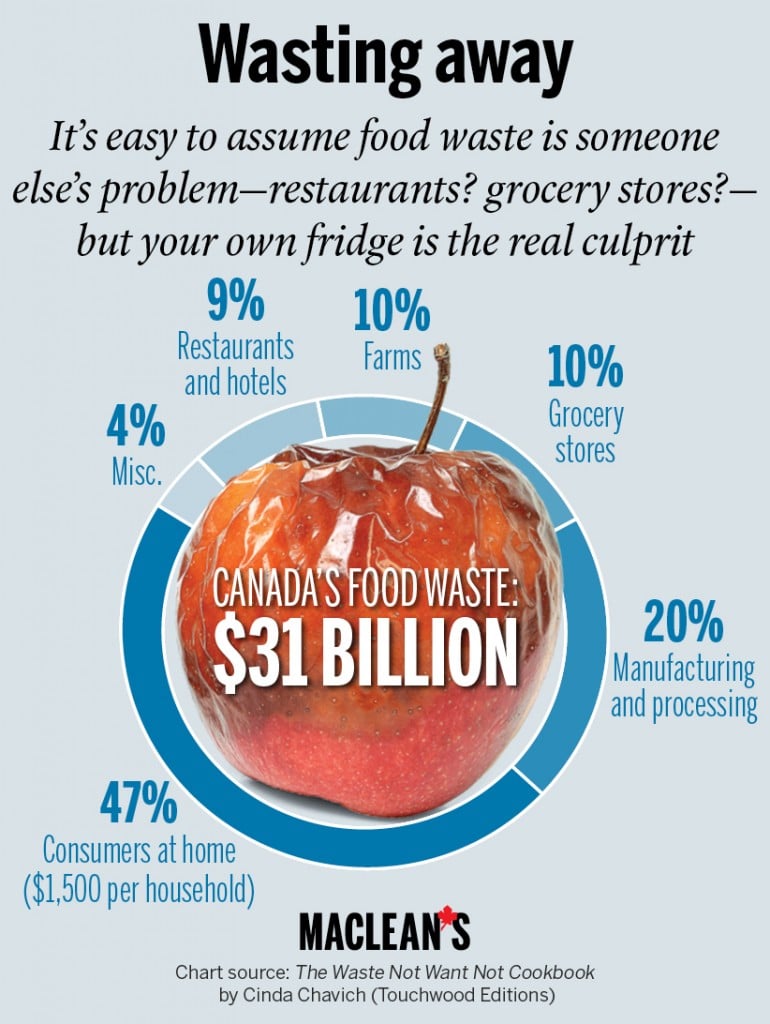

Still, that ethic is slowly taking hold as governments, cities and businesses around the world turn their attention to the global issue of food waste. A staggering 40 per cent of the food produced in the developed world (and 30 per cent worldwide) is never consumed. It’s food that’s discarded from farm to fork, tossed in the field because it’s not the right size or shape, cycled through stores and restaurants, and chucked out of every single family’s home refrigerator. In fact, half of the estimated US$1 trillion worth of food the UN says is discarded each year is the wilted lettuce and expired milk that’s dumped by consumers, with another 20 per cent tossed by grocery stores and restaurants. Dana Gunders, a scientist at the U.S. National Resource Defense Council (NRDC), found $150 billion worth of edible food ends up rotting in American landfills and producing methane, a greenhouse gas 20 times more damaging than CO2. Meanwhile, food production uses 80 per cent of all fresh water consumed in the U.S. If food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world, after China and the U.S., and a major contributor to global warming.

When Vancouver couple Grant Baldwin and Jen Rustemeyer decided to spend six months eating nothing but discarded food for their recent documentary Just Eat It, they found mountains of bagged salads, sealed yogourt and packaged baked goods in city dumpsters. At one point, Baldwin dives into an 5.4-metre bin brimming with tubs of hummus, dumped due to mislabelling but with more than three weeks left on the product’s “best before” date (another arbitrary industry practice that leads to trashing of perfectly safe and edible foodstuffs).

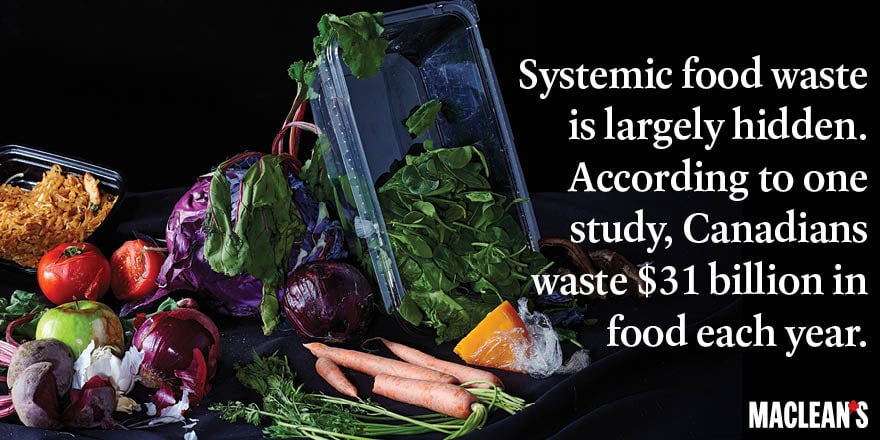

Systemic food waste is largely hidden, and Canada is behind the curve when it comes to addressing the issue. According to the Ontario-based consulting firm Value Chain Management International (VCMI), Canadians waste $31 billion in food each year. VCMI, a private firm that specializes in helping companies in the agriculture and food industries maximize profits, is the only organization that’s been tracking the impacts of food waste in Canada. “The first real body of work highlighting the problem of food waste is from the NRDC—we don’t have an NRDC in Canada,” says Martin Gooch, VCMI’s founder and CEO.

We also don’t have a national food-waste policy in Canada. “I find that intriguing,” says Gooch, an adjunct professor in management and economics at the University of Guelph. “Governments are more regionalized here. In the U.S. and U.K. things are more centralized, and in those countries there are greater resources and motivation to get something going.”

Many say consumers, in Canada and beyond, are ultimately to blame. We want it all: cheap, perfect, unblemished fruits and vegetables of a certain size and shape. So perfectly good tomatoes too ripe to be trucked across the country or too large for a supermarket “three-pack” are rejected. Apples showing the scars of rubbing against a leaf or branch never get to the store. A scene in Just Eat It shows celery farmers in California discarding more than half of each plant, trimming away outside ribs and leaves to deliver a right-sized celery heart to fit perfectly into a plastic bag. All of the “trim” is left lying in the field.

The EU has made some strides when it comes to food waste. Tristram Stuart, the author of the 2009 book Waste: Uncovering the Global Food Scandal, shamed EU regulators into rescinding rules that made it illegal to sell produce that didn’t meet strict cosmetic standards; once, only straight cucumbers and bananas with a particular length and curvature were acceptable. Now the UN has declared an international war on food waste, and selling these imperfect fruits and vegetables is a growing trend.

You are about to hear more about food waste here in Canada, too. The West Coast is leading the way for change. While many municipalities across Canada encourage household composting of food scraps, in Vancouver, it’s now mandatory for all—as of Jan. 1, 2015, the organic waste ban applies to homes, apartment buildings, restaurants, grocery chains and all institutions serving food. Similar bans are in place in San Francisco, Seattle, Halifax and Nanaimo, B.C.

Residents can see Vancouver’s campaign on billboards and buses, half-eaten spring rolls and melons announcing, “Hey! Food isn’t garbage.” This spring, Metro Vancouver will launch its own version of the U.K. website for consumers—called Love Food, Hate Waste—a first in Canada.

Vancouver treats food waste as “a resource,” says Carrie Hightower, a technical adviser in Metro Vancouver’s zero-waste implementation program, sending it to commercial composters like Harvest Power where an anaerobic digester converts organic waste into green energy.

While the B.C. Restaurant and Food Services Association has said the food scraps ban will be devastating to small restaurants, many have adjusted. In a pilot study based on the LeanPath food-waste prevention system developed in Portland, Ore., high-profile Vancouver eateries including Campagnolo, Vij’s and the Four Seasons Hotel learned to track and reduce their food waste. No one wants to run out of food at a wedding or banquet, says Four Seasons executive chef Ned Bell, but measuring what’s wasted in a big kitchen is an eye-opener. “Most hotels already compost but we had scales in the kitchen to weigh food scraps before they went into the green bin,” says Bell. “It prints out a report—‘throwing away 10 kg of shortribs’ —that really helps everyone in the kitchen understand the problem.”

Chris Whittaker, the chef behind Forage, a fully sustainable and zero-waste restaurant in Vancouver’s Listel Hotel, says a few changes netted big results. “The breadbasket was the No. 1 cause of food waste because 50 per cent of people don’t eat it,” says Whittaker, “and it was going straight into the bin. The style of service helps, too. With small plates there’s 50 to 60 per cent less wasted food coming back to the kitchen.”

Calen McNeil, owner of Victoria’s Big Wheel Burger, is proving that even fast food can be carbon neutral. Thanks to recyclable food containers and cutlery, composting, and shrinking the portion size of their popular fries, there’s now only one garbage pickup every six weeks at the busy burger joint. By buying a $100 carbon credit every month, MacNeil has eliminated Big Wheel’s “carbon foodprint.” “Restaurants are one of the highest carbon-producing businesses per square foot,” says McNeil, who is also behind Victoria’s Food Eco-District, Canada’s first carbon-neutral restaurant district. “It may be slightly more expensive to compost but you are going to be paying to remove your garbage anyway.”

Most businesses do not know how much food they waste. Sonya Fiorini, director of corporate responsibility for Loblaw, Canada’s largest food retailer, cannot say how much food the company discards but says it’s working with Gooch at VCMI “to get at what’s wasted and why it’s wasted.” She says Loblaw has “grinding mills” at 38 of its stores, designed to divert food waste to anaerobic digesters in southern Ontario. And, following the French supermarket chain, Intermarché, Loblaw sells “naturally imperfect” apples and potatoes, produce deemed too “ugly” by the industry, at discounted prices to prevent food waste.

It’s a step in the right direction, says Gooch— reducing food waste at the source, not just recycling it. “The focus on cheap food and on volume is a symptom of a broken system, one that’s unsustainable in the long term,” he says. “Encouraging composting or feeding animals with food scraps may look good as a PR exercise but it’s a sodding expensive way to produce animal feed and dirt.”