Jesus was son of god—and a husband?

From 2014: Evidence suggests Jesus may have been married, rekindling a debate that’s as old as Christianity itself

Share

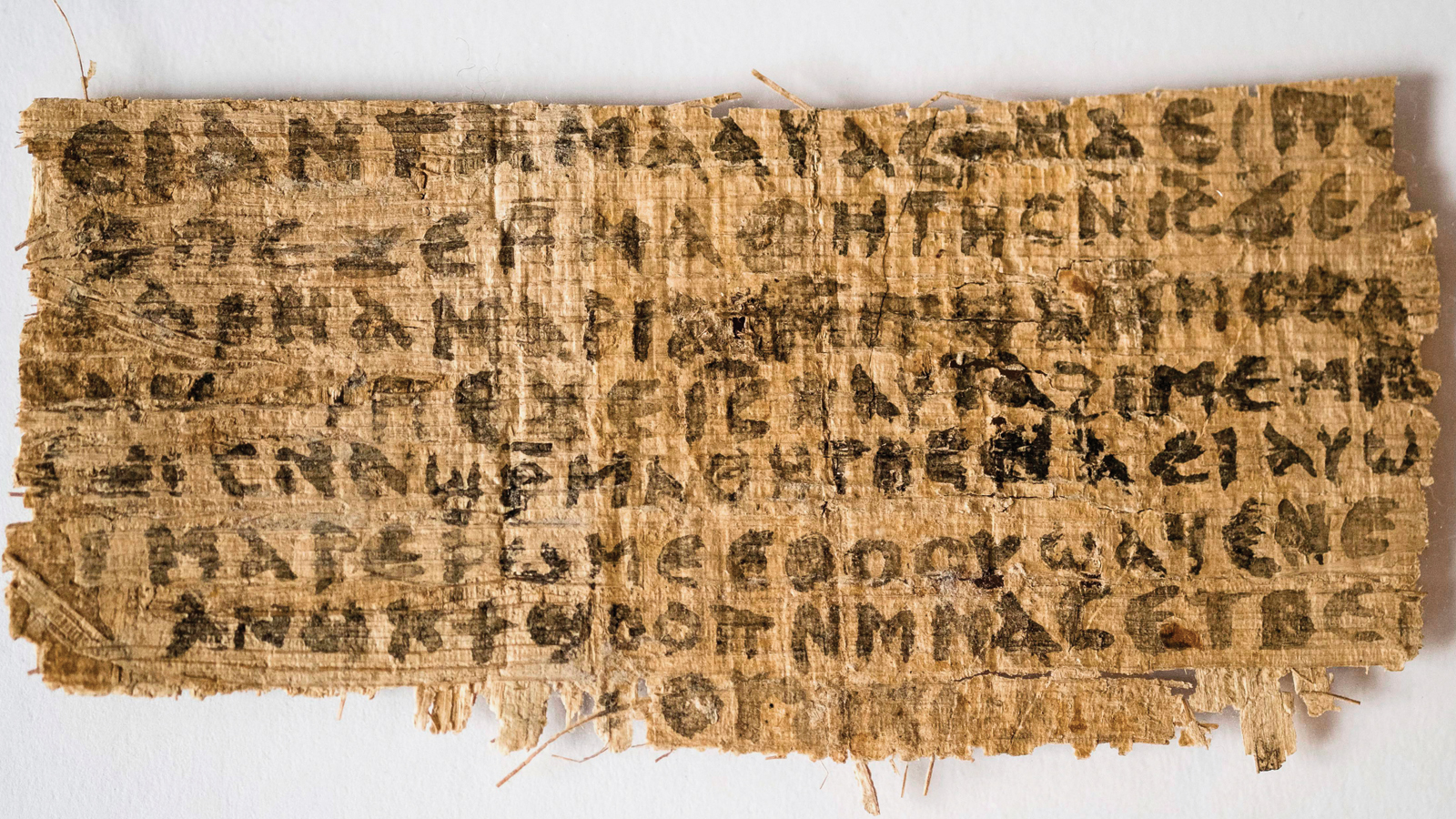

The tiny, tantalizing fragment of papyrus—on which a handful of words record Jesus Christ referring to “my wife”— is not a forgery after all, or so the world’s media have decided. The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife, as Harvard divinity professor Karen King named it 18 months ago when she announced its existence to great controversy, is indeed ancient. At least the actual four-centimetre-by-eight centimetre piece of papyrus is old (laboratory tests have dated it to about the eighth century CE) and the ink betrays no sign of modern chemical admixtures. For scholars faced with its murky provenance—it has no history before the anonymous donor who loaned it to King acquired it in the 1960s in Communist East Germany—the fragment has taken a solid, but minimal, step toward authenticity. As the more skeptical experts point out, if you don’t want your forgery to be exposed in a heartbeat, you really need to craft your modern message with ancient materials.

Translated from the ancient Egyptian language known, like Egypt’s native Christian Church itself, as Coptic, the entire papyrus yields 52 English words, broken into sentence fragments. The three that stand out are: “Jesus said to them. ‘My wife . . .,’” “She will be able to be my disciple . . . ,” and “Mary is worthy of it.” It’s reasonable to conclude, as King stated, that the main topic of the original document was to affirm that “mothers and wives can be disciples of Jesus—a topic that was hotly debated in early Christianity as celibate virginity increasingly became highly valued.”

That’s assuming it is genuine.There are still a lot of reasons to look askance at it, according to historian Anthony Le Donne, author of The Wife of Jesus, a marvellous survey of ancient and modern attitudes toward Jesus’s possible marriage. There’s the “strangeness of its bad Coptic grammar,” for one, particularly the way it replicates a typo found in an online Coptic-English translation resource, something that might indicate “a forger with an Internet connection.” The age of the papyrus is as puzzling as it is reassuring—the eighth century is not an era during which scholars think Christ’s marital state was a live issue. (Does it indicate a forger with access to old, but not old enough, papyri?) But, adds Le Donne in an interview, nothing raises hackles as much as the way that “it’s emerged at the right time in the history of Christianity to get a lot of traction.”

He’s entirely right about the fragment’s contemporary resonance. The media’s intense attention in 2012, its current uncritical acceptance of what the physical tests really mean—the very motive for a forgery, if forgery it is—all show just how hot a topic the (possible) bride of Christ is. Credit Dan Brown and The Da Vinci Code’s tittilating claim that Jesus and Mary Magdalene wed, starting a family whose descendents are still alive. Or, more broadly, modern debates over the meaning of marriage, for the urgency of current interest, but the fascination is nothing new.

In the later second century, long after anyone who knew the circumstances of Jesus of Nazareth’s actual life was dead and gone, Christians began debating the question of his marital status. As the religion founded in his name grew to dominance in the West, the answer was no longer a mere matter of historical fact, but deeply consequential—often unconsciously so—in our assumptions about marriage, sexuality and how we should live our own lives, as well as the role of women in the Church and in society.

Over the centuries, as mainstream Christianity developed its views, other Westerners—some Christian, some not—have sought their own validation in Jesus’s life. From ancient ascetics—eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven—to celibate Catholic clergy and married Protestant pastors, to polygamous Mormons and gay Christians, they have found the Christ, and the wife of Christ, they wanted.

The ascetic side of Greek dualism, the flesh-spirit divide that has proved so enduring in Western thought, rapidly became influential in early Christianity. The second-century followers of Christ who were the first to declare that Jesus was unmarried were actually heretics—insomuch as they ended up on the wrong side of still-evolving orthodoxy. The heretics’ Jesus only appeared to be human; his true spiritual self never touched the material world. Not only did he leave no footprints when he walked, historian Le Donne adds, some thought “Jesus had super-special bowels” and never defecated. Given that, it’s anti-climactic to add that their Jesus was not a husband.

Orthodox Christians, who believed Jesus was as human as he was divine, rejected all of that—except for the celibacy. Most physical processes were necessary for life, but sexual activity was a choice, one Jesus did not need to make. The heretics were right that he never wed, asserted the influential second-century theologian Clement of Alexandria, but for the wrong reasons: Jesus had no need of progeny to carry on his bloodline because he was eternal. The unmarried conclusion, which became Christianity’s belief for centuries, suited the ascetic-minded Church leaders’ attitudes toward sex. It suited, too, their misogyny, proving helpful on another front.

Le Donne notes how the New Testament is very clear that the group around Jesus during his ministry included “women important in their own right, not attached as usual to a man—described as the ‘wife of so-and-so’, or the ‘sister of’—Salome and Mary Magdelene in particular.” The early Church “didn’t know what to do with them; there’s evidence of very early moves to marginalize their role, but they can’t quite do it, they can’t write the women out of the story because they’re too well remembered.” A married Jesus would be powerful ammunition for Christians who believed that since women were apostles then they could be religious leaders once again. That is, almost certainly, what the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife is attempting to convey.

But that strain of Christian belief fell away before evolving orthodoxy, which established the single and celibate Jesus as its default position. It’s essentially an argument from silence—the Gospels do not mention a wife—Le Donne points out, and he argues powerfully that it does not hold up. Not even Jesus’s sisters merit their names recorded in the Gospel of Mark when his neighbours marvel at his preaching. “Is not this the carpenter,” they ask, “the son of Mary, and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon? Are not his sisters here with us?” Wives, too, were simultaneously ubiquitous and ignored in Jesus’s world, and there is no reason even his spouse would have been mentioned. We know St. Peter was married not because an evangelist mentions his wife, but because Mark records Jesus entering his house and healing the first pope’s mother-in-law of her fever.

There is another scriptural reference to Peter’s marriage, one that is even more telling about what was utterly normal among Jesus’s first followers. In the First Epistle to the Corinthians, St. Paul, seemingly finding a need to explain his outlier status—he was unmarried—insists upon his right, at some future time, “to be accompanied by a believing wife, even as the rest of the apostles and the brothers of the Lord and Peter.” Those references do not necessarily mean Jesus was married, Le Donne cautions—note Paul did not say “a wife like the Lord himself had”—but they make both norms manifest—wives were present and (almost) always unmentioned.

In Western culture, Jesus’s unquestioned celibate status sailed right through the Protestant Reformation’s rejection of Roman Catholicism’s relatively late enforcement of clerical celibacy. But in 19th-century America, a radically new church took a different view. Brigham Young, the Mormon leader who took the Latter-day Saints from Illinois to Utah after the assassination of their leader, Joseph Smith, was originally rocked when Smith confided the revelation about polygamy to him. “I felt as if the grave was better for me,” he later explained. But Young, like most of Smith’s more prominent followers, eventually came around: he wed 55 women before his death, including two of his mother-in-laws. Soon, like other religious leaders who wanted to assure themselves their own lives emulated Jesus’s, he was certain Jesus, too, was polygamous. Late in life, talking of a scriptural reference to Jesus’s “train,” Young added, “I do not know who they were, unless his wives and children.” From no wife, to as many as a patriarch.

Le Donne sees a similar pattern working out amongst other marginalized groups. “Christians, and not just Christians, always want Jesus as their advocate, and he ends up on both sides, speaking for the outsiders and for the establishment.” When Elton John said, “I think Jesus was a compassionate, super-intelligent gay man who understood human problems,” he was reflecting a whole new possibility in the modern imagination for an unmarried man, now that our most intimate relationships were no longer economic unions dedicated to perpetuating bloodlines.

For almost 2,000 years, claim and counter-claim about Jesus’s sexual activity and marital life went on without much speculation about whom that wife might have been. The whole while, the legend of Mary Magdalene rose as her actual story submerged, and inevitably the twain met. She was clearly among the most important followers of Jesus, male or female, the first to whom he appeared when he rose from the dead. Mary appears in several extra-canonical Gospel fragments—possibly including the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife, although the sheer number of women named Mary in the Biblical Gospels makes it difficult to be sure she is the “Mary” found there—many of which have as a theme the male disciples’ jealousy of her. In the Gospel of Thomas, Peter complains to Jesus that, “Mary should leave us, for females are not worthy of life.” Jesus’s response—that he would make her male—shows the text is not to be taken literally. But Mary’s early eminence is clear.

That went by the wayside when Pope Gregory I, in 591 CE , for reasons that are unclear—honest confusion seems the most likely—conflated Mary Magdalene with another Mary and with an unnamed female “sinner,” turning her into a reformed prostitute. Ironically, it was the making of Mary Magdalene in the Western imagination. Hundreds of medieval churches were named after the fallen but repentant Magdalene, while legends turned her into the owner of a large part of Jerusalem, so rich, beautiful and given to pleasure she was known only as “the sinner.” The modern Western assumption of the universal importance of individual sexuality, the same thinking that could contemplate a gay Christ, had a ready-made, highly sexualized—rich and well-connected, to boot—candidate for the role of Mrs. Christ. First presented in the 1953 novel The Last Temptation of Christ and later developed in the alternative history Holy Blood, Holy Grail, it eventually formed the backdrop of Dan Brown’s megaseller.The marriage of Jesus and Mary is now virtually an accepted fact for millions.

The fact this is all about sexuality rather than family norms is revealed by the almost complete lack of interest in Jesus as father, compared to Jesus as lover or husband. Children merit as little attention in the Gospels as wives do, but in Jesus’s case it can be argued that their absence from the Gospels is more meaningful than that of a wife. The New Testament rather smoothly glosses over what may have been a succession crisis after the crucifixion—Jesus’s brother James, seemingly on the sidelines throughout Jesus’s ministry, emerges as the new leader of his brother’s followers, and not as regent for a nephew or guardian for a niece.

What are the odds then, that Jesus of Nazareth was married? At some point in his life, very high, Le Donne concludes. He was, after all, 30 years of age or so when he began to preach, a mature man by any account in a society that valued marriage. “My default position,” says Le Donne, “is that a younger Jesus would have done the honourable thing, honoured his mother and father, followed the God of Genesis’s first command: be fruitful and multiply.” In an agrarian society where one in 10 or more women died in childbirth and an even higher percentage of children did not survive to adulthood, that does not necessarily mean Jesus had any immediate family alive when he began to preach.

That’s where the historian’s analysis becomes most intriguing. “When the most important thing in your culture is the continuation of your line and your people’s line, to say the strange things Jesus says about marriage and family shows a radical non-conformist, a man who found his family in his followers.” This is the rabbi who tells listeners that anyone “who does not hate his own father and mother and wife and children and brothers and sisters” cannot be his follower; who will not let a disciple depart to bury his father; who rejects his own blood kin by saying those listening to him are “my mother and my brothers”; who thinks there is good cause to become a eunuch for the sake of heaven. Can this man have had a wife while he was preaching that message? Not likely, Le Donne thinks; nowhere near as likely that we will go on looking for her all the same, while really looking for ourselves.