Millennials don’t think they’re doomed

New poll finds they’re not nearly as pessimistic as often assumed

Photograph by Derek Mortensen

Share

They’ve been called Generation Screwed. Born in the wake of the demographics-dominating Baby Boomers, the much-mythologized Generation X, and Gen Y (whatever that is), the Millennials—kids coming of age in this century—are supposed to be in tough.

You’ve probably heard the dispiriting prediction: This is supposed to be the first generation of Canadians who won’t do as well as their parents. Saddled with the debt of the big spenders who came before them, stuck in a “new normal” era of slower economic growth, the Millennials are often said to face bleak prospects.

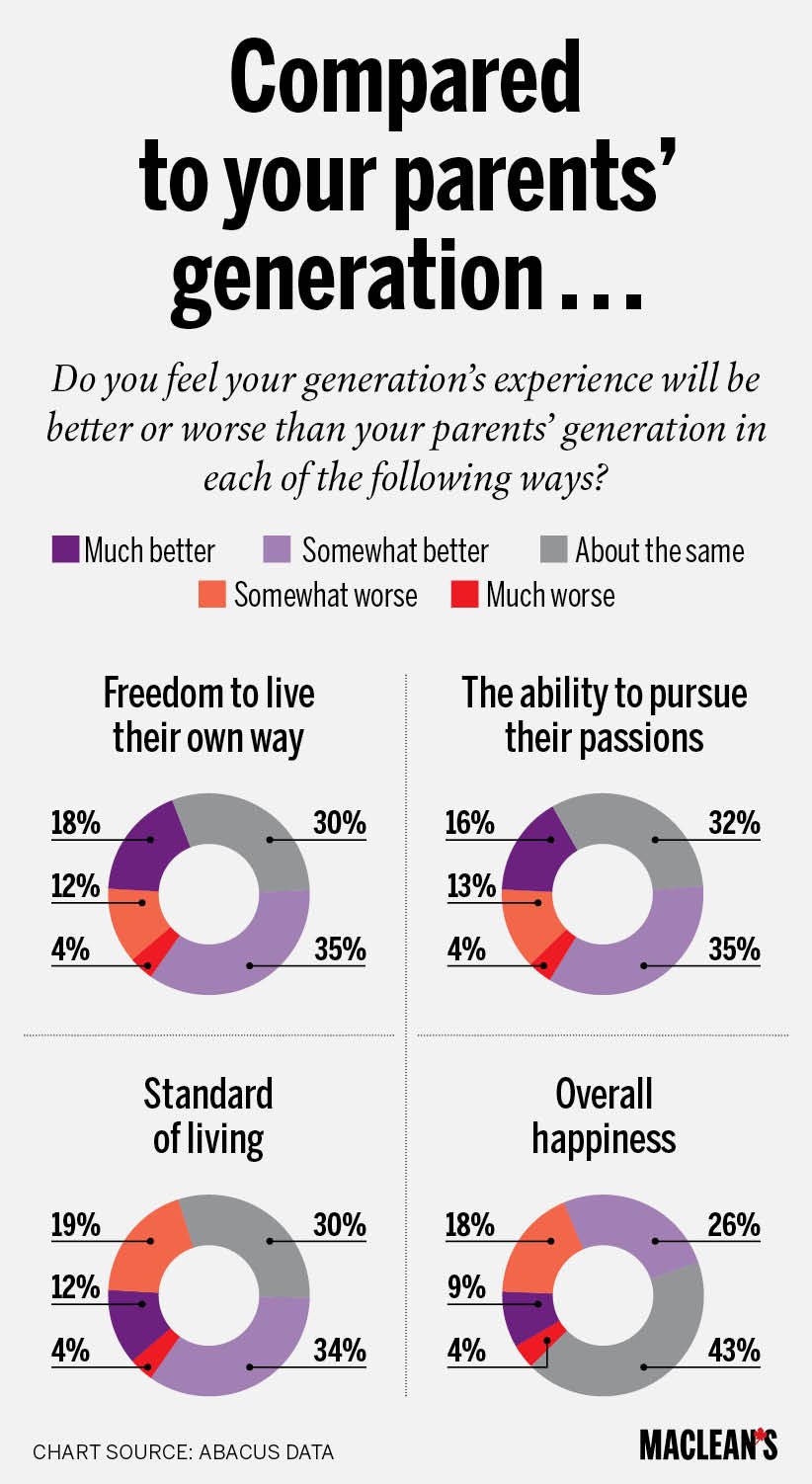

But a new poll by the Ottawa-based firm Abacus Data, commissioned by the blue-chip Canadian Council of Chief Executives, has found that young Canadians just don’t believe they have it so bad. In fact, most look forward to experiencing lives equally or more prosperous and happy than their elders.

Asked how they expect to fare compared with their parents’ generation, most Canadians aged 18 to 35 surveyed by Abacus were upbeat. Less than one-quarter of them said they believe their age cohort will fail to live up to their parents’ overall level of happiness or standard of living. Nearly half, 46 per cent, expect their own generation’s standard of living to rise above that of their mothers and fathers, while about a third, 32 per cent, anticipate roughly matching their parents’ living standards.

Abacus chief executive officer David Coletto, who oversaw the poll—and is himself only 33—said the remaining roughly one-quarter of young Canadians who expect to fall short of their parents is still significant, “but nowhere near what we’ve heard about this generation being overly pessimistic.”

The generally sunny outlook doesn’t appear to reflect any delusions about the job market. In fact, the 18- to 35-year-olds surveyed seem to have a realistic view of how tough it might be to get established on a career path. Asked about job opportunities for people like them, 48 per cent said they were good or excellent, but a shade more, 51 per cent, rated the employment prospects poor or very poor.

As well, Coletto pointed out that respondents who are aged 18 to 24, many of whom are still in school, tended to be more optimistic about their employment prospects than those aged 25 to 35, most of whom have experienced a job hunt. “Once you actually hit the ground and reality sort of strikes you, it does have an impact on optimism,” he said.

![ABACUS_CHARTS1new[1]](https://cms.macleans.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ABACUS_CHARTS1new1.jpg)

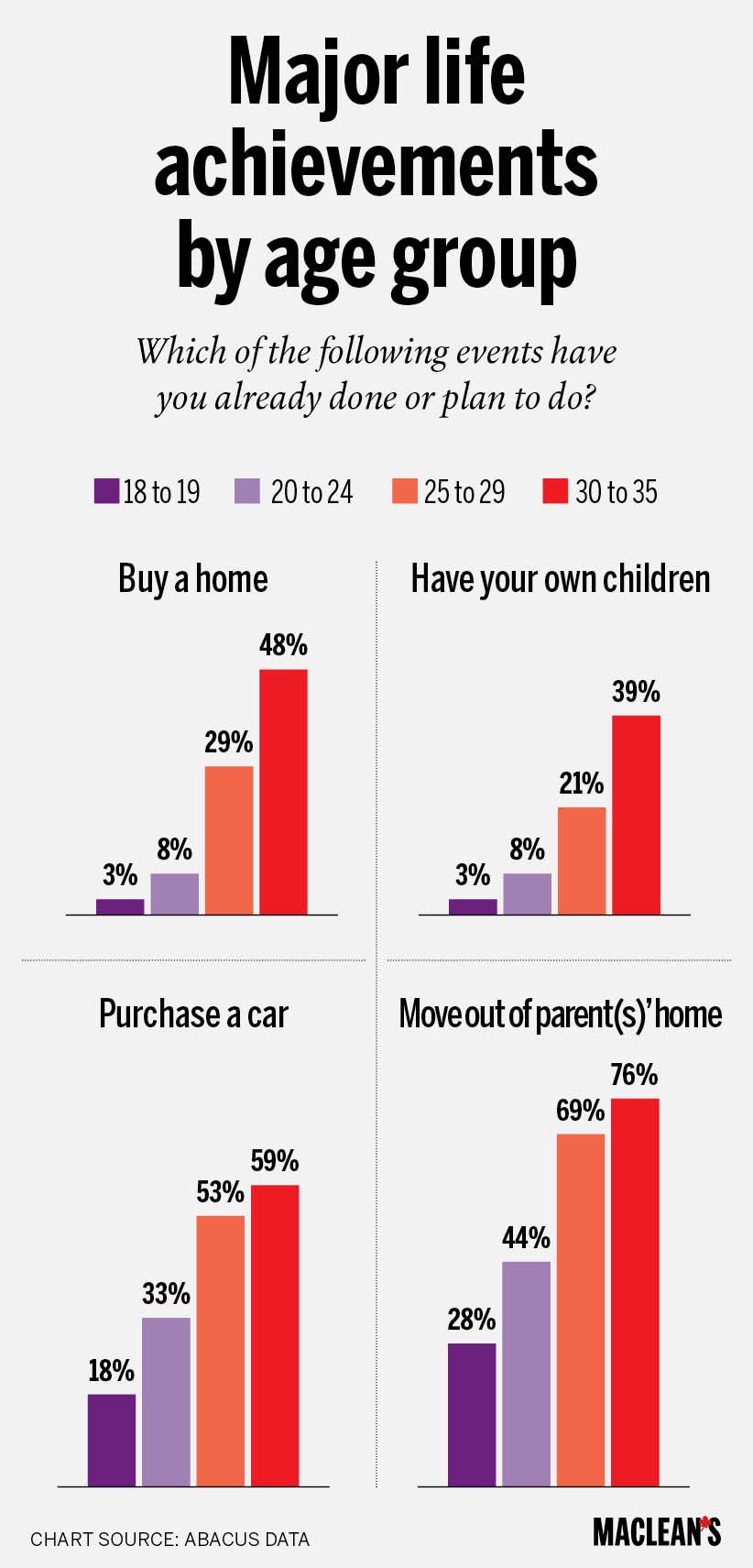

Another indicator that many young Canadians, while remaining hopeful, have prudently adjusted their outlooks, is that they often expect to hit watershed moments later in their lives than previous generations did.

That’s already happening. Among millennials aged 30 to 35, only 19 per cent have achieved all six of these traditional milestones of adulthood: moved out of their parents home, achieved financial independence, finished post-secondary school, found full-time work, bought a home, and had children.

“We do almost see arrested development,” Coletto said. “It does demonstrate that some of the financial realities are preventing young people from moving out and becoming financially independent.”

But he’s not talking them down. Coletto said he was glad, as a member of the generation under the scrutiny, to conduct this particular study. “It’s a little different,” he said, “than somebody older going to the zoo and saying, ‘Look at all those Millennials.’ ”

The Abacus study, based on interviews conducted March 19-25 with 1,700 Canadians aged 18 to 35, was commissioned by the Canadian Council of Chief Executives for a conference it is holding next week in Ottawa, called “Creating Opportunities: Jobs and Skills for the 21st Century.”

![ABACUS_CHARTS2new[1]](https://cms.macleans.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/ABACUS_CHARTS2new1.jpg)