The Iron Soldier: How Trevor Greene learned to walk again

Nine years after Capt. Trevor Greene took an axe to the head in Afghanistan, he is walking again. It’s a journey that could change lives.

Trevor Greene learning to use the reWalk exoskeleton in Nanaimo, BC on August 6, 2015. Photograph by Jimmy Jeong;

Share

Trevor Greene has a new tattoo on his left forearm. It appears to show a rugged mountain peak and, above it, a string of letters I can’t decipher. It’s mid-June, an exciting morning for the forcibly retired Army Reserve captain, his wife, Debbie, and a cast of characters who crowd the main floor of the Greene family home in Nanaimo, B.C. Greene, in his wheelchair, is sharing the focus of attention with a silent partner sitting nearby, something that looks eerily like a headless robot. The Greenes, in ways they couldn’t possibly have foreseen, have been building to this moment for more than nine years, really, since the aftermath of March 4, 2006, the day Capt. Greene first did the impossible by refusing to die in the dust of a remote Afghan settlement.

By 2006, the Canadian Forces had long since abandoned the concept of peacekeeping; our soldiers were in a shooting war against the Taliban. It was Greene’s role, as civil-military co-operation officer, to build bridges to a more peaceful future by offering aid and infrastructure assistance to impoverished villages in Kandahar province. It is why he was sitting on the ground with the elders of Shinkay village, why he had set down his rifle and removed his helmet as signs of respect; why, as he spoke of Canada’s desire to help this village, he was vulnerable to a 16-year-old who crept up behind him, pulled a crude axe from his cloak and slammed it into Greene’s skull with a cry of “Allahu akbar” (God is great). Greene’s eyes rolled back in his head as he slumped unconscious, blood and brain spilling on the ground. The assailant was killed in a fusillade of Canadian bullets, but his attack signalled the start of a Taliban ambush. As Canadian soldiers fought back, a medic worked to stabilize Greene, and platoon commander Kevin Schamuhn radioed for a helicopter rescue. At Kandahar base, an incredulous radio operator asked that the cause of the injury be repeated. “I say again,” snapped Schamuhn, “the nature of the wound is an axe to the head. Over.”

That Greene survived the primitive brutality of the attack was the first of many times he has stretched credulity and defied conventional medical wisdom on the road from Afghanistan to recovery. We are here this morning for the next stage in a long journey. The wheelchair he now uses he sees as a temporary measure. Walking is his goal: “walking unaided,” says the 50-year-old. “Actually, running and climbing and swimming. Surfing.” He is about to be strapped into a device called ReWalk, an Israeli-designed robotic exoskeleton that provides powered hip and knee motion. It was created to let those with spinal cord injuries stand upright and walk with the aid of crutches. Today, if things go well, Greene will use the device to take his first powered steps.

As final adjustments are made, I’m talking with Greene and Ryan D’Arcy, a neuroscientist and expert in brain imaging at Simon Fraser University (SFU) and Surrey Memorial Hospital, who has been tracking Greene’s physical recovery since 2010 as his brain builds new neural pathways to compensate for the traumatic injury. I ask Greene about the tattoo and the lettering. “Himalayas,” he says, “Chomolungma,” the Tibetan name for Everest. “I’m going to hike to the base camp.”

“I promise we’ll do that together,” says D’Arcy. “I’m going to hold you to it,” says Greene. “I’ll hold you to it,” says D’Arcy. “It’s the other way around.” D’Arcy wonders if ReWalk, which is capable of taking people up stairs, could handle such a climb. “I won’t be using this,” says Greene. ReWalk, in his view, is just another step until his brain sorts out his mobility problems. How will he get to base camp? “My legs,” he says.

This goal seems, well, outrageous. But, in the seven years of visiting and corresponding with Trevor and Debbie, I have seen where hope can carry you when it is harnessed to hard work and determination. I remember their previous house in Nanaimo, with its overhead rail and hoist system needed to lift him in and out of bed (not needed now, thank you), and the giant wheelchair that used to be necessary to support his floppy neck and back. His arms and core have grown stronger. The guy whose brain was nearly cut in half in 2006, who stared down death and fought the demons of post-traumatic stress, stood between parallel bars in 2010 to exchange wedding vows with Debbie. “I promise to always push you beyond your limits so that you can reach your fullest potential,” she said, sweetly issuing marching orders after slipping the ring on his finger. And she has. In 2012, March Forth was published, the searing and inspiring account of the journey thus far that they co-wrote. Also that year, Debbie gave birth to their son, Noah, now three. He’s a brother to their daughter, Grace, now 10, who was one year old when Greene deployed to Afghanistan. Last year, Greene, finding his voice as an environmentalist, co-wrote with a friend There Is No Planet B, about the precarious state of the world’s health and of the people and innovations that offer hope of recovery. Hope is such a big little word in his vocabulary.

Jay Courant, the worldwide training director for ReWalk, is fitting Greene into the device. Watching the process is Carolyn Sparrey, an assistant professor at SFU in the evolving field of mechatronics, a mechanical-engineering hybrid. “My research is around human injury and treating the human body like a mechanical system,” says Sparrey, who advised on the ReWalk purchase. The device has a backpack, hip support, legs, knees and feet. Greene settles onto the device as though sitting on its lap. It beeps and whirs as Courant adjusts the limbs and straps Greene in. It is metal, batteries and motors, guided by proprietary software and a remote-control watch. It’s a vaguely humanoid, somewhat otherworldly bit of machinery. But how it came to join the Greene family, and a resulting convergence of events that may inspire a legacy beyond one man’s quest to walk again—that is where the heart rests and the magic lives.

The Greenes’ hunt for an exoskeleton, which they saw as the next tool in his rehabilitation, began in late 2012. Grade 12 student Rebecca Lumley, inspired by a Remembrance Day talk Trevor gave at her Nanaimo school, launched a social media fundraising campaign. It caught the attention of Inga Kruse, executive director of the B.C and Yukon command of the Royal Canadian Legion.

Kruse met with the Greenes and offered the Legion’s services as a fundraiser. “Trevor said something to me I will never forget. He said, ‘I don’t want this paid for by Veterans Affairs or you, or anybody. I’ve already used up enough money; it should go to somebody else.’ ” Though taken aback, Kruse framed it as a business proposition. The Legion, in its 90th year, is showing its age. In her command, there are 149 branches, and falling. “My big concern is that, in 10 years’ time, we will not have Legions, or very few of them,” she said in a June interview at the command’s modest Surrey headquarters. “We need society to join the Legion. Poppy campaigns are great, but they don’t run our business.”

In Trevor she saw a mutual opportunity. He already had a reputation as a medical marvel. The Legion was ahead of the curve in supporting veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). An exoskeleton would signal a new direction, a new relevance. “The Legion is looking at this as an advanced technology experiment,” she said. “There are people who have lost their legs, lost their limbs, who have all kinds of different reasons to need some sort of robotic interface or device. If we were the first to make that happen for one guy, that’s what we care about.”

That was the case she made to the Greenes. “There’s something in it for us, as well,” she told them. “We have to put on a cape when the Bat Light came on.”

And so the crisis precipitated by the twisted ideology of an axe-wielding Afghan teen morphed from a cause seized by a Nanaimo student to an opportunity for the 55,000 members of the provincial and territorial command—the veterans and others who stand on street corners, wrapped against the November chill, to sell poppies.

Kruse figured it would take 18 months for the branches to raise the necessary $100,000. She cried “stop” after just three months when the fund, primarily from poppy sales, topped $123,000. Greene calls it “awe-inspiring” how the branches took up the call. “For most of my life, the Legion has been an old-man’s organization. But my generation of veterans has benefited so much from the Legion.”

The organization can be “a fundraising juggernaut,” Kruse said, but that doesn’t negate the larger problem she sees of an aging membership, struggling with dwindling finances to keep lights on in community branches across her command and, indeed, across the country. “It takes a long time to turn the Titanic, but we know the iceberg is coming,” she said. “That’s the difference between us and the Titanic. We see it.”

What she wasn’t sharing in June, over coffee and cookies, was that plans were under way for something more ambitious than getting one veteran walking. Some of those involved in Greene’s “Project Iron Soldier,” as it came to be called, were hatching a plan with the potential to help hundreds, perhaps thousands, of veterans, to alter the course of their support and health care delivery and, if the stars align, to lift Legion branches back on their financial feet.

Partnered with neuroscientist D’Arcy in the Iron Soldier project is veteran health care administrator Rowena Rizzotti, the former executive director of clinical programs and operations for the Surrey-based Fraser Health Authority. Both are champions of Innovation Boulevard, a partnership among government, the health authority, higher education and business, to create a centre of excellence for health technology, applied research and new approaches to care delivery. As they met with Kruse, they batted around the notion of a Legion legacy to build on the support for Greene’s quest to walk. They found it in their own backyard. Located within the footprint of Innovation Boulevard is Surrey’s Whalley Legion branch 229, a prime site already zoned for high-density redevelopment.

Both women saw its potential. “The Legion right now, they have limited dollars, but they do have land,” says Rizzotti. Having worked in both hospital and seniors’ care administration, she knows there is a looming crisis in care, while Kruse is painfully aware of the gaps in support for veterans. The population of seniors will double by 2036, only magnifying the costs and the current “abysmal” level of service, says Rizzotti. “As a result, they’re landing in acute care centres, they’re landing in emergency departments. They have very few social supports, a very little network of health services to support them in their community and to live at home in a dignified way.”

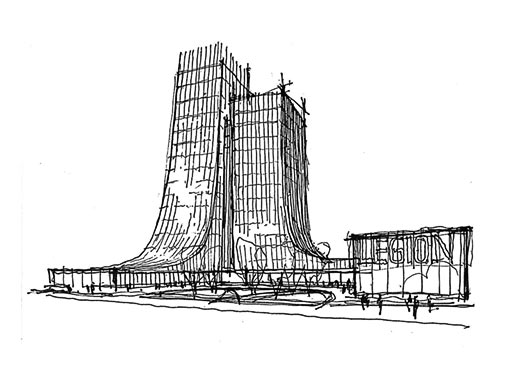

The result, in remarkably short order, is a proposed 20-storey-plus Legion Veterans Village on the site of branch 229. It would include a modernized Legion branch and, of course, a venerable bar. Surrounding that would be: a centre of excellence for PTSD and mental health treatment; facilities for rehabilitation, assistive devices and robotics; temporary-stay apartments for families of soldiers under treatment; as well as a spectrum of veterans’ residences, from supportive and assisted-living to long-term care.

The site would remain a self-sustaining, Legion-owned facility, but Rizzotti has founded a non-profit Institute for Healthcare Innovation to shepherd the proposal, fundraise, mine grants, and seek out development partnerships. The proposal has been a military-grade secret, but will be revealed on Sept. 17 in a double-barrelled announcement at the Surrey campus of SFU.

Greene will be a guest of honour, and the hope is to offer the first public demonstration of his ReWalk device. As well, renderings will be released of the veterans’-village proposal. It is inspired in its sweeping design by the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France. Its exterior would be festooned with poppies, a design element that carries into the interior. “It will be a monument to veterans,” says Kruse, calling it “Part 2” of Greene’s story. “This is our dream coming true for him . . . the right approach, the right way of looking at mobility and independent living. We see this as being a national beacon for the honour and respect for veterans.”

Rizzotti sees the potential to apply the model of developing veterans’ and seniors’ care facilities at Legion sites across the country. “The courage that Trevor has shared, it takes those kinds of stories,” she says, “to demonstrate how this can change the lives of millions.”

Jay Courant is based in San Francisco, but he travels the world getting spinal-cord-damaged patients back on their feet. ReWalk is designed, and approved in the U.S. and most countries, for use on people with paraplegia. Most have no sensation below the waist, so, when the device lifts them onto their feet, they have a strange feeling of floating, he says. And of joy. “It’s usually somewhat dramatic,” he says. “Regardless of the language, the face always says the same thing: that smile.” Invariably, people seem to want to hug, after years of the awkward contortions from reaching out in their wheelchairs. “Standing up, you hug face-to-face. So they hug, and everyone cries.”

ReWalk is not meant to replace a wheelchair; it’s a supplementary device to exercise and challenge the body. There are huge benefits from getting out of a chair for a time and becoming vertical. “When you think about it, if someone made you sit in a chair for a year, what would happen to your body? Then do that for 20 years. It’s horrible, all the things that change,” says Courant. “Every [ReWalk] user who’s been studied has lost fat mass. Every incomplete user, someone who has some partial ability, has gained lean leg mass. We see changes and improvements in bowel function, bladder function, sleep, cardiorespiratory function. Every system in the body, almost, is affected positively.”

There are warning beeps and the whirr of motors as the device lifts Greene upright. He gasps. It isn’t from pain, he explains later, just the sudden, unfamiliar sensation of being wrenched upright. Greene, at six foot four, is at the absolute limits of the device. Courant, who is hanging on protectively, is the only one in the room tall enough to look Greene in the eye. Greene is smiling and a bit apprehensive. He is hanging onto an aluminum walking frame for support. Courant is holding him at the back for support. Debbie is in front to guide the walker.

Another beep and whirr. Greene’s right leg kicks back, then forward. And they are off, a little parade moving from living room to kitchen. “Whoa!” says Greene, the mechanical man. “How does it feel?” Debbie asks of his first steps in the device. “Crazy,” he says. They reach the kitchen wall, a journey of about eight metres—and nine years. They turn around. “I haven’t seen you walk that fast in a long time,” says Debbie. “Trev was a very fast walker before.”

They make several more circuits over the course of the day, and set another date in August for further trials. There’s a sense of optimism and momentum, but things aren’t ideal. The walker is too narrow and it impedes progress. The device is meant to be used with crutches. Although Greene’s arms and shoulders are vastly stronger and more mobile than they were, the right arm still lacks sufficient tone to safely support him. “We can work on that,” says Debbie. She leaves to pick up Grace from school. “Does that mean Daddy is going to walk?” Grace asks. The first goal, Debbie tells her, is getting around the block.

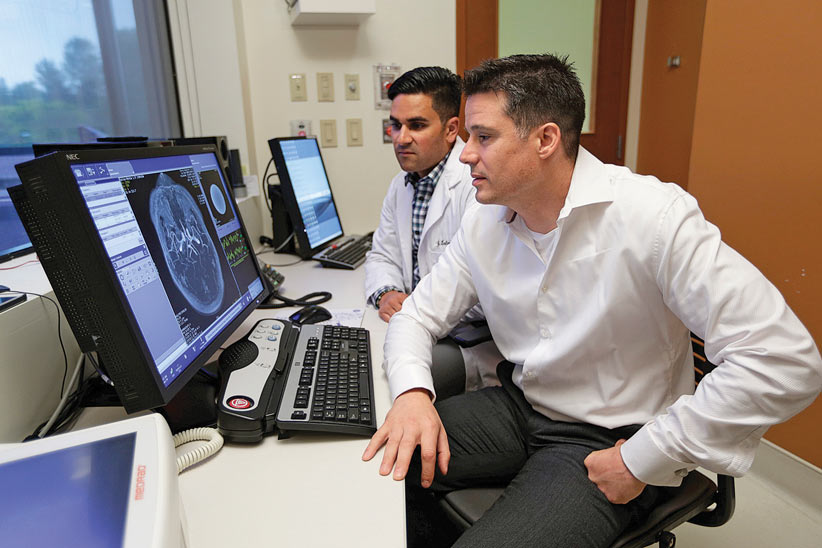

D’Arcy is leading Phase 2 of a research study on the first time a ReWalk has been used for someone with a traumatic brain injury. The device is just a tool; the focus is on tracking, with next-generation scanning technology, the changes in Greene’s brain over time. Will using the device trigger new brain circuits sufficiently to improve mobility and, perhaps, to eventually let Greene walk unaided?

This evolving concept of “neuroplasticity,” of the brain’s ability to heal and rewire, is already on display in a first-phase study with Greene and D’Arcy’s research team. Indeed, the results of that study, “Long-term motor recovery after severe traumatic brain injury—beyond established limits,” will be published this fall in the Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. The study tracked the brain changes and mobility improvements that came from Greene’s continued rehabilitation efforts. It also showed that his use of mental imagery activated the same regions of the brain when he visualized a sport he formerly excelled in: competitive rowing.

The study demonstrated, at least in Greene’s case, that long-term rehabilitation and, perhaps, visualization of exercise, can lead to improved motor function. It also showed, in heartening news for stroke and other brain-injury patients, that improvements needn’t stop after the generally accepted six-month to two-year window for post-trauma rehabilitation. “The main objective,” the study says, “was to directly address a major barrier in the treatment of brain injury: underestimating the brain’s potential for recovery.” Its conclusion: “Continued benefits in physical function due to rehabilitation efforts can be achieved for many years following injury.” Or, as Greene says, with a soldier’s bluntness of the doctors who wrote off his prospects of recovery, “I call bulls–t. After six months, doctors give up, so the patient gives up. It’s a crime. I think that loss of hope would be devastating.”

At the end of that June day, Greene is spent. He slumps in his wheelchair, head back, eyes closed. I ask how he feels. “You know when you . . .” He trails off. “Let me think about that.” Days later, Greene sends an email with the heading, “After much solemn contemplation . . .” And this message: “The exoskeleton feels like being dry-humped by a robot.”

There’s another test run in August, in a rented barn-like structure in a Nanaimo park. It has a smooth cement floor and room to roam. Courant runs a training session on the device for Debbie, as well as physiotherapist Anna Kania and Edna Ricafrente, Greene’s long-time care aid. Greene puts in two days of trials on the ReWalk prototype. His own device, a next-generation machine, is still in production. Things go better with a larger walking frame, but the use of crutches is still beyond reach. Courant warns Debbie that she and Trevor will walk a fine line between safety and progress. “If you can’t let them fail, they won’t improve,” he says. “That’s the hard part.”

Sitting outside in the sun before the second day of training, Courant says their typical clients, those with full upper-body control, would likely be walking in the device unaided by now. Greene, with his traumatic brain injury, is an atypical case, the most complex he’s dealt with. “I hope he can progress to crutches to give him much more functionality in the device,” he says. “Will he do that? I don’t know. I certainly hope so. Will he walk more independently? I hope so. It seems like, all along, he’s continued to defy medicine to show that the [brain] plasticity process is still happening for him. I hope it continues.”

Weeks later, with D’Arcy in his NeuroTech lab in Surrey, I ask about Greene’s quest to reach Everest base camp. Those with brain injuries are often unaware of their limitations, hampering their motivation to work at recovery. (Greene had told me of a time, back when he was largely immobile in an Alberta rehab centre, when he’d told Debbie he’d just walked to the store. “Did anybody see you?” she’d asked. Eventually, “the penny dropped,” and he knew he was deluding himself. Did the realization depress him? “It was better, actually,” he said. “I knew my mission.”)

D’Arcy frames his response to the Everest question by discussing the medical concept of false hope. “When people have major changes like brain injury, it’s important to have them understand the impacts and significance of it. The default is to make sure you clinically help someone come to grips with the extent of that. You never want to give somebody false hope.” Here, too, is a fine line to walk. When does that become a demotivating factor? As Debbie has said, Trevor’s significant improvements came more than two years after his injury. “There are lots of people proving for themselves that they can make small steps, and when you look back over time, you actually come quite a long way,” D’Arcy says. Not a week goes by at this lab, he adds, when people recovering from brain injury “aren’t motivated by Trevor’s courage.”

His small steps, robotic or otherwise, now reach back almost a decade. From the blood and betrayal of a March day in Kandahar, he has moved on to build with Debbie a beautiful family and the proverbial village of support. His stubborn quest to walk has inspired Legion members, and may yet prove the catalyst for the creation of a real village—one made of concrete, full of hope and purpose, and covered with poppies. So, define impossible.

“What’s the issue with setting goals as high as you possibly can?” asks his friend D’Arcy. “Set it to the top of the world. Why not?”