Gentleman Jean Béliveau: From the Maclean’s archives

‘It’s tempting to say they don’t make ’em like Béliveau any more, but in a sense, they never did’

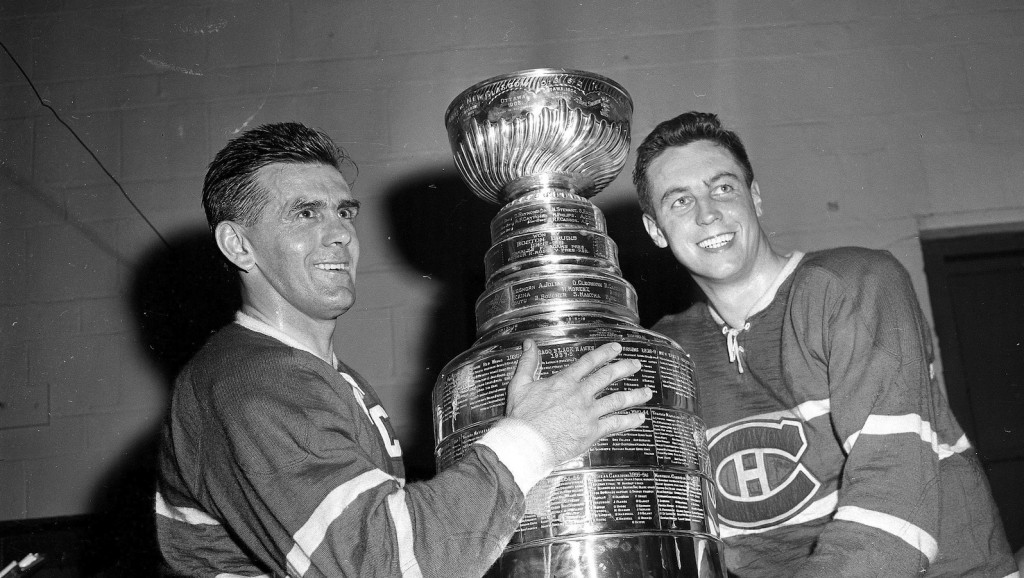

Maurice Richard (left) and Jean Beliveau, of the Montreal Canadiens smile happily in the dressing room with the Stanley Cup after defeating the Boston Bruins 5-3 at the Boston Garden on April 20, 1958 to win the National Hockey League Championship. (AP Photo)

Share

This column by Anthony Wilson-Smith was first published in May 2000:

On one of hundreds of such occasions for him in the mid-1970s, Jean Béliveau — by then a vice-president of the Montreal Canadiens — agreed to autograph some photos and appear at a minor hockey banquet in west-end Montreal. As a result, he one day received in his office a gangly, nervous teen-age male who was one of the event organizers. By the manner in which Béliveau behaved, he might have been receiving the CEO of a major corporation, or visiting head of state: he showed the guest around his office, offered to fetch him a soft drink and called him, without a trace of irony, “Sir.” When the visit was over, the guest, more awed than ever, told Béliveau he felt honoured. No, the host said solemnly: “You do me the honour by wanting me at your dinner.”

It’s tempting to say they don’t make ’em like Béliveau any more, but in a sense, they never did: he’s one of a kind in any era. Béliveau’s coach of 13 years, Toe Blake, a man not given to superlatives, once said: “I have never heard any derogatory comments about him. As a hockey player and gentleman, Jean Béliveau has no equal.” Blunt, smart Glen Sather, a guy who built his own successful playing career on his remarkable ability to take the mickey out of big stars, is equally admiring on the subject of Béliveau as player and man. So you can see why, for fans of a certain age, the report last week that the now 68-year-old Béliveau is being treated for a cancerous tumour struck so hard.

It’s easy to get depressed about our unofficial national game these days: the NHL increasingly resembles the World Wrestling Federation, no Canadian teams are in the final rounds of the playoffs, our national team couldn’t win a medal in the worlds and even Don Cherry doesn’t sound as pumped up about it all as he once was. Ask anyone over age 20, and they’ll tell you the game isn’t what it was.

That’s true, but nothing in life stays static. Perhaps the best book ever written on any sport is Ken Dryden’s The Game. Even then, in 1983, a couple of seasons removed from his time with the great 1970s Montreal dynasty, Dryden worried about the state of hockey. Canadians, he wrote, “never precocious, never rebellious, reasonably content, ride [others’] coattails and do pretty well. In hockey, now that we’ve been caught from behind, we wonder why it took so long.”

It’s 28 years since the epochal Canada-Soviet Union summit series of 1972: most people who know their hockey agree that players now are far more skilled, better-conditioned and faster than they were then. At the same time, there’s no question Canada’s bragging rights in world hockey are past the due date. The most tired cliche of sports journalists annually is to hope that the supposedly unmatched guts and heart of our national teams will allow us to vanquish other, better-equipped foes. The flip side is if we’re so reliant on those qualities, we’re conceding the Finns, Swedes, Czechs, et al, are now more talented, smarter and better coached than us.

Dryden was once asked what he thought was the golden period of hockey. The answer, he said perceptively, is whatever era it was when you were 12 years old: the players you watched then will always seem bigger and better than anyone. A few years ago, the hockey association in my old neighbourhood held a fund-raising golf tournament, and invited several players who had gone on to the NHL. That night, a few guys sat around and reminisced. One former NHLer, who put in close to a decade in the pros, looked across at older acquaintances who never rose past junior, and said, solemnly: “You guys, you really knew how to play.” There’s the same curious awe in Wayne Gretzky’s voice when he talks of players he came up against in early NHL days — none of whom had a fraction of his talent.

It’s fair to resent trends that, over the years, have driven ticket prices so high, but it’s wrong to dislike athletes simply because they now make huge money. It shouldn’t be hard to understand why guys from modest roots show off when they make it big. A friend from Northern Ontario, who now works as an Ottawa reporter, had drinks a while back with two Liberal MPs who started trashing Brian Mulroney. What, the friend inquired, did they specifically resent? The Gucci shoes, the big house, the expensive lifestyle, they answered. The friend was unimpressed. Where I come from, he said, everyone who makes it big would behave like that: it’s what we dreamed of as kids. Athletes are no exception. It’s also wrong to suggest there are no nice guys in hockey anymore. Curtis Joseph of the Leafs donates time and money to helping kids — and was mortified when that became public. Paul Kariya has manners that would make any mom proud. Gretzky is an appropriate idol in any era. And so on.

And then there’s Béliveau. In 1998, shortly after he became a companion of the Order of Canada — the country’s highest honour — the onetime kid who had met him in the mid-1970s saw him on a flight to Toronto. Béliveau was besieged, signing autographs and shaking hands with well-wishers. “Mr. Béliveau,” someone said, “your award makes us all proud.” “Sir,” Béliveau protested, “no one is more proud than me.” Some things, happily, don’t change, like the matchless grace of le Gros Bill, hockey’s Man for All Seasons. Get well, Mr. Béliveau.