Meet the RV dwellers facing eviction in Tofino, B.C.

RV living serves as affordable housing for the oceanside town’s workers, who say there’s nothing wrong with their way of life

Tina Halcorn poses outside of her home at the Crab Apple Campground, where she has been living since Oct. 2019. (Photograph by Melissa Renwick)

Share

Melissa Leonard finishes her bartending shift and hears the familiar crash of waves on her bike ride home, the sound carried in on the breeze from the open Pacific. But home itself—an RV on a campground facing closure—reminds her she might not be here much longer.

The 28-year-old transplant from Montreal works in Tofino, B.C.’s idyllic ocean playground framed by stretches of sand and lush rainforest. Now she feels she’s being pushed out of paradise. “I don’t know how to really survive through this whole transition,” Leonard says. “It feels like they just want locals to leave.”

Leonard and her partner, who until recently managed a popular restaurant called SoBo (short for “sophisticated bohemian”), bought an RV trailer and have been renting a space year-round at the Crab Apple Campground, a 1.7-acre site tucked away on a corner of the Pacific Rim Highway.

The property is known for housing employees who serve the area’s thriving tourism industry. But in April, the district rejected the campground’s permit application, potentially leaving its 50 residents in the lurch when the current one expires in October. Year-round residential campsites do not exist in Tofino’s zoning bylaws.

RELATED: Renters across Canada are banding together to fight high housing costs and evictions

The decision was a contentious one. Campground dwellers argue there’s nothing wrong with their way of living, and that it perfectly suits service workers in a village with limited housing: they demonstrated and circulated a petition that garnered more than 1,700 signatures.

But some permanent residents raised safety and security concerns, suggesting the site encourages transitory living and pointing to the camper vans and motorhomes proliferating on side streets and vacant lots throughout town. Several Facebook comments call Crab Apple an “eyesore.”

ELECTION 2021: Party Platform Guide

Once a commercial fishing town, Tofino is now a resort haven for surfers, hikers and foodies. Its base population of 1,900 swells enormously as the weather warms, with as many as 750,000 people a year, according to provincial estimates. And the rise of tourism as an economic driver quickly transformed the community’s housing needs. Travellers to Tofino were sleeping in vans long before #vanlife—living on wheels, cheaply, while following job opportunities—trended. The local tourism board even uses a Tofino-branded Volkswagen bus as part of its promotions.

Leonard’s Crab Apple neighbour, Tina Alcorn, is one of the trans-provincial migrants. Five years ago, she hopped the first flight she’d ever taken out of her hometown of Halifax, with a dream of “expanding” her life. Over time, she bought a white 1998 Vanguard Fifth Wheel with turquoise decals, and became the manager of Tofino’s Co-op grocery store. “I’m finally making some traction on a career and now this rug is being pulled out from underneath me,” she says. “It’s definitely a lot of panic.”

Like many business operators in town, Alcorn has posted a “help wanted” sign at the Co-op—reflecting a dilemma that the district of Tofino acknowledges: working people are said to be leaving because they can’t find housing, putting a labour squeeze on local businesses. While rates at the Crab Apple start at $400 a month, a one-bedroom apartment in Tofino rents at $1,300. Buying an apartment of that size would cost roughly $785,000.

Communities throughout B.C. are grappling with the same problem, in many cases siding with anti-RV residents. Over the last year, Vancouver, Kelowna, Kamloops and Nanaimo have all asked permanent RV dwellers to leave. Squamish and Surrey recently passed bylaws preventing people from overnighting in vans or RVs.

But a few places have tried to balance residents’ concerns against the need to house workers. Tofino’s neighbouring municipality, Ucluelet, recently rolled out a pilot program allowing landowners or businesses to host RVs and fast-tracking permits for seasonal-worker campsites. Leonard and her partner hope to move there.

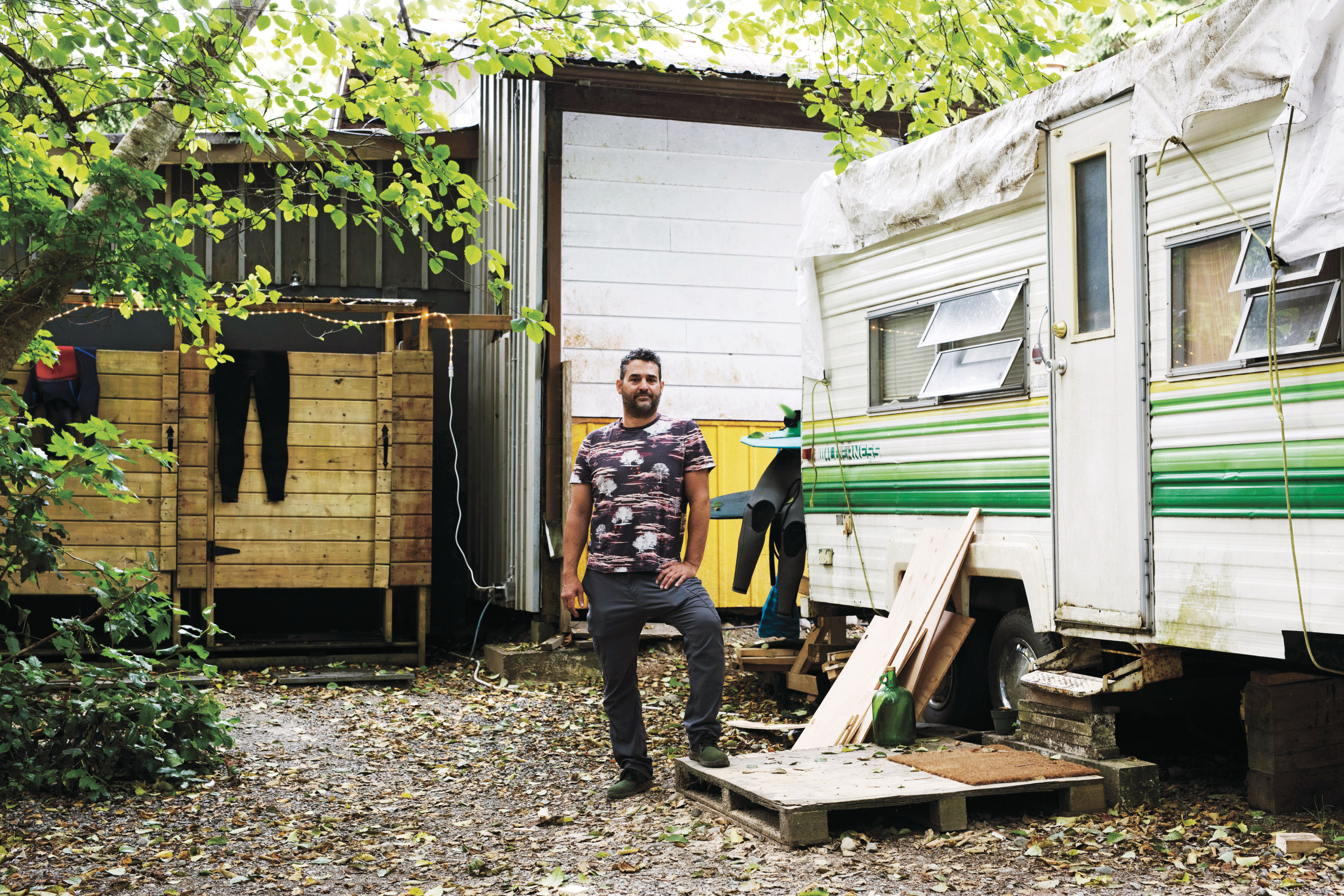

Back in Tofino, Crab Apple’s owner finds the situation devastating. Mathieu Amin, 45, first leased the land for his small floral design business in 2008. Within months, a local in a camper van asked to rent a spot there and, seeing a need, Amin obliged. “I had the space,” he says.

He operated illegally until he scraped together financing to purchase the Crab Apple land five years ago. Right after, he applied for his first three-year, temporary-use permit at the request of the district. By then, he was housing more than 25 people.

Amin had gotten a series of extensions, but emotions ran high at the April district council meeting when his latest renewal request came up. According to B.C.’s Municipal Act, only two consecutive temporary-use permits can be granted. And Dan Law, Tofino’s mayor, says the district’s new Official Community Plan prioritizes permanent housing. “Nobody in the room wants to evict people from their homes,” he says. “We had to be very careful that what we’re doing is in the best long-term interest of everybody.”

MORE: If you thought the cutting of B.C.’s ancient forests was winding down, you’d be wrong

Amin is revamping his application on the recommendation of council but doubts it will be approved by October. Where RV-dwelling workers will go in the meantime is not clear.

Mandy Nordhan, who owns the Meares Vista Inn motel, acknowledges council’s need to balance worries about affordability and safety, with so many people coming in and out of the community. But RV life, she says, “is the way out here for some people.”

Nordhan came to Tofino in 2012 after the hotel she owned in Grand Forks, B.C., burned down. For months, she and her family lived in a trailer, saving money to renovate the motel. She has rented space on her property to campers for almost a decade. One, who works at a local surf shop, has lived there eight years.

Some of Nordhan’s guests complain the RVs are unsightly, but she’ll hear none of it. “They’re the people making your breakfast, they’re the people teaching you how to surf,” she responds. “The town will die if there’s nobody to work.”

This article appears in print in the September 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Decamping paradise.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.