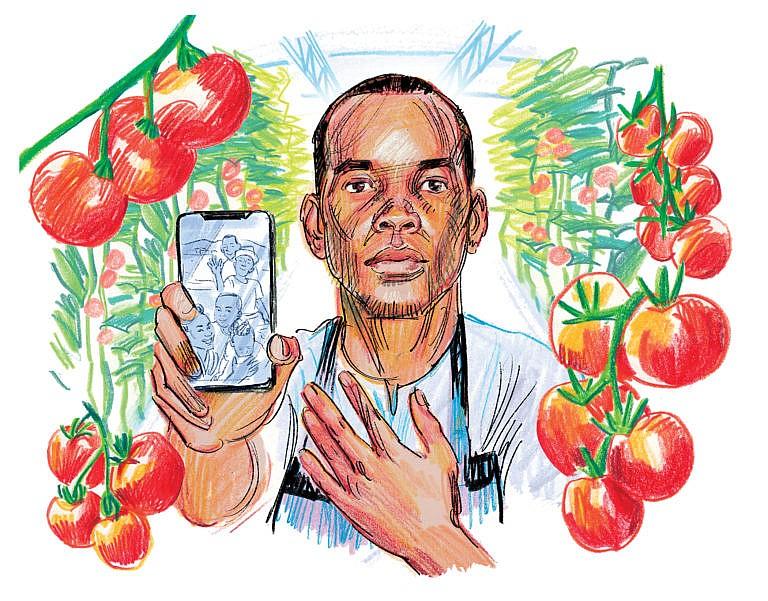

I came to work in Ontario thirteen years ago. I don’t know when my family can join me.

I spend 12 hours a day in a greenhouse, but the hardest part of my job is being apart from family

Share

I grew up in a small farming community called Aux Lyon in St. Lucia. As a young boy, I yearned to travel, so when my eldest sister told me there was an opportunity to work in Canada, I immediately filled out an application to be a temporary foreign worker. I came to Ontario in 2010, when I was 24 years old, to work in a greenhouse that grew more than 100 varieties of tomatoes. Nothing about Canada was familiar to me. I lived in a 64-person bunkhouse, with eight people to a room. We had no Wi-Fi, which made calling home very expensive. At first, working in the greenhouse was exciting because agriculture in Canada is light years away from what we have in St. Lucia, where we plant tomatoes with back-wrenching labour, using machetes, forks and spades. Here, farmers have hydroponic systems and tractors. I absorbed all the knowledge I could because I wanted to improve our agriculture back home and own a hydroponic greenhouse one day.

Over 13 years, I flew back home many times for breaks. In St. Lucia, I got married and now have three sons—my eldest is 14—who live with my wife. We video call every day, but being away from my family is the hardest part of the job. In 2019, I promised my wife that I would come back to St. Lucia for good. When I returned, I tried to start a greenhouse, but COVID-19 hit. Markets closed down, and I had nowhere to sell my produce.

READ: I escaped Mexico’s cartels. Fourteen years later, the only work I can find is as a janitor.

In September that year, my former employer called and asked me work in his new greenhouse in Canada. I initially turned him down, but a couple of months later, I changed my mind because I spent all of my money on my greenhouse. Now, I’m back in Ontario. Monday to Friday, I work 12-hour days. I spend the first six hours winding tomato plants on trees and clipping them to stay in place. For the next six hours, I remove all the plants’ suckers, and on Saturdays, I do other tasks like deleafing.

In the last two or three months, something has changed in me. The work used to be so exciting—sometimes we competed against each other when we clipped plants, and our employers gave gift cards to the best workers. Lately, I want to do more. Working long hours is tiring, and you get injuries. When the temperatures get too high, our employers let us do easier tasks or leave early. After work, I go back to a bunkhouse with 24 guys—it’s in good condition, but privacy is an issue. On Sundays, I try to bury myself in other things, like studying for a business administration degree or playing video games. The time off is hard. It reminds me that I don’t have any family in Canada.

But I have a plan. The best way to move my wife and kids here is to become a permanent resident. In 2021, I heard about a permanent resident pathway program and applied. I went to London, Ontario, to take the CELPIP, or English exam, which I passed. I gathered the rest of my information, and an immigration lawyer told me she’d call back about my application. That night, I waited until I fell asleep around 1 a.m. Two hours later, the phone rang, but I didn’t answer.

RELATED: As a woman, I had no opportunities in Japan. My world opened up when I got to Canada.

In the morning, I saw a message: the program had reached its cap, and I had to start over. In March of 2022, I came back to Canada so I could apply again. A lawyer is helping me, but since my CELPIP exam expired, I have to pay to retake it. There are so many barriers to permanent residency. Some of the requirements aren’t relevant to labourers who work in roles like mine, which is where Canadian businesses need help. So why would it hinder them in the future? Foreign workers can usually speak English, but they aren’t always confident they can pass the exam. Applicants also need to have a high school education, which I do, but many workers don’t. Another issue is money. I’ve spent over $12,000 on application costs, exam costs, passports and lawyers.

I don’t think temporary workers are automatically entitled to permanent residency, but the government should remove some unnecessary obstacles. My wife is excited to come here. She’s good with taking care of children and the elderly, and my kids would grow up to have jobs here too. Canada has a worker shortage; if we could move our families here, it would solve a lot of problems.