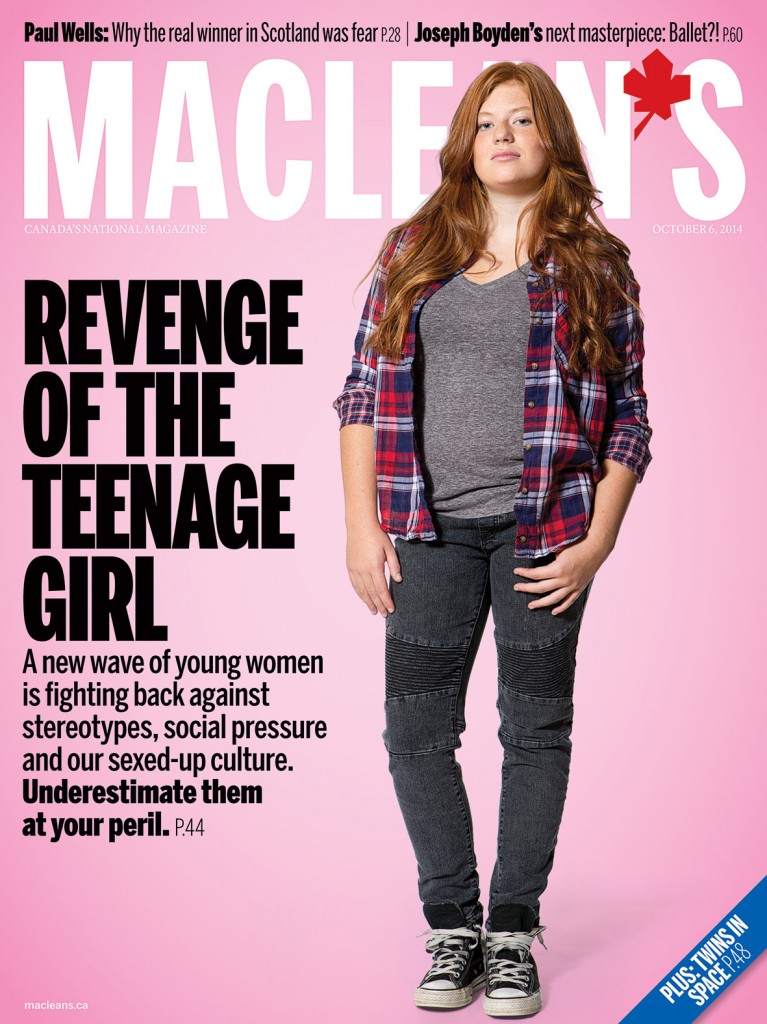

Revenge of the teenage girl

Teenage girls are taking on social stereotypes and a sex-saturated culture. Ignore them at your peril.

Share

Johanna Morrigan, the protagonist of Caitlin Moran’s new coming-of-age novel How to Build a Girl, is an unlikely heroine next to fictional superstars Katniss Everdeen and Bella Swan. Johanna is smart, well-read, and funny; she’s also a fat, poor and lonely 14-year-old growing up in 1990s post-Thatcher Britain who can’t wait to escape the crowded council flat in a destitute West Midlands town where she lives with her parents and four siblings. Sex is a preoccupation; she is eager to lose her virginity (a goal she accomplishes). Johanna’s adolescent sexual adventures do not leave her dead or subject to other moral punishment. Nor is there any deus ex machina Cinderella transformation so common in contemporary stories about plain young women. Instead, she’s the author of her own script. She reinvents herself as “Dolly Wilde,” earns a coveted job as a music journalist, and sails into a bright, big future at age 17.

Comparisons to Moran’s own life, as described in her autobiographical 2010 book, How To Be a Woman, are inescapable. Moran, now 39, also grew up in public housing and left home at 16 to become a music writer. She’s now an acclaimed columnist for the Times and Britain’s most prominent feminist. Moran created Johanna to fill what she saw as a void in the current culture, she says in an interview with Maclean’s—a normal girl who enjoys sex and is in control of her sexuality. “There are only about five kinds of girls you ever see reflected in popular culture, but there are 3.3 billion women out there. I wanted to show a girl having fun—learning her lessons, but having fun and enjoying being alive.”

Movie rights to the book have been sold; Moran’s writing the script. A sequel is in the works, How To Be Famous, followed by How To Change the World. “I want teenage girls to think differently, because that’s what art and culture always did for me—made me feel that I could change the world. I want to pass on that feeling of electric possibility to anybody who reads my stuff. I want to make girls see the kind of girls they want to be.”

“You can’t be what you can’t see,” Moran says, quoting Marie Wilson, of the White House Project, an initiative dedicated to increasing female representation in American public life. “So the more of these girls we see, the more of these girls we’ll see.”

It’s already happening, Moran says, noting girls come up to her at readings and say, “ ‘I’ve formed a feminist society at school, this is what we’re talking about.’ They have a brilliant and innate sense that they can now go and take their place in the world.” Girls united are an amazing and powerful thing that has never happened before, Moran says. “I’m thrilled I have 11- and 13-year-old daughters now because this is without question the best time to be a girl in history.”

How to Build a Girl arrives as the voices of teenage girls have taken on cultural currency. Globally, young women are seeing how they are being marginalized and they are speaking out. At the forefront is Malala Yousafzai, the celebrated 17-year-old Pakistani blogger and activist, marquee speaker and bestselling author, famed for fighting for girls’ access to education and equal rights in her country. She came to international prominence after a 2012 assassination attempt.

In the West, activism surrounds girls being sent home for wearing clothing deemed “distracting.” Last week a group of high school students in Staten Island—90 per cent of them girls—received detentions for wearing tank tops and shorts to school. The insurrection follows on the heels of a female high school student in Florida being made to wear a “shame suit”—oversized red sweatpants and a neon yellow shirt, both with the words “Dress code violation” written on them.

“It’s archaic, making appearance more important than education,” says Lilinaz Evans, a 16-year-old feminist activist in London, England. “I know schools [in the U.K.] that make girls kneel on the floor; if their skirt doesn’t touch, they get detention. Or if someone’s hair is not the right colour a lot of schools will send a girl—it’s very rarely a boy—home.” The policies are disrespectful to boys as well, says Evans: “It’s saying they can’t control themselves if they see an inch of shoulder.”

Without the Internet, she would never have become a feminist, says Evans. It exposed her to the voices of women she never would have heard. Evans, “admin queen” of the Twitter Youth Feminist Army, is also involved in Campaign4Consent, a program to make schools teach consent as part of sex education classes. She reports an upsurge in young feminist groups in London, from one to close to 100 in three years.

Related reading:

Get ready for Generation Z: They’re smarter than Boomers, and way more ambitious than millennials

The no-baby boom: Social infertility, baby regret and what it means that shocking numbers of women are not having children

The secret lives of networked teens: Sarah Boyd on balancing parenting and privacy

Evans points to the influence of 18-year-old American Tavi Gevinson, who gained fame at age 12 for her Style Rookie blog and later fused feminism and popular culture on Rookie, a magazine for teenage girls. Adora Svitak, a 17-year-old activist and Berkeley university freshman, observes that the personal has become political for her and her peers dealing with the threat of campus rape, street harassment, access to reproductive health internationally, as well as “slut shaming,” blaming women for sexual assaults.

Still, in 2014 feminism remains a cultural flashpoint, as entertainers make headlines for rejecting—or accepting—the label. According to Moran’s simple test to determine whether a woman is a feminist—made famous in How to Be a Woman—the decision is not difficult: “Do you have a vagina? And do you want to be in charge of it? If you said ‘yes’ to both, then congratulations—you’re a feminist!”

Katy Perry, she of the whipped-cream-squirting breasts, has declared she isn’t a feminist, as have actor Shailene Woodley and singer Kelly Clarkson. “I think when people hear ‘feminist,’ it’s just like, ‘Get out of my way, I don’t need anyone,’ ” Clarkson told Time. Others embrace the label, among them 17-year-old New Zealand singer Lorde, Miley Cyrus (she of the ice-cream-cone pasties), Mindy Kaling and Elle Fanning. Knowing its capacity to stoke controversy, Beyoncé shrewdly used the word “feminist” as the all-caps backdrop for her performance at the MTV Video Music Awards last month. And just this week, Emma Watson, a United Nations “women goodwill ambassador” and co-star of the Harry Potter films, delivered a powerful speech at the UN for “HeForShe,” a campaign to galvanize one billion men and boys to help end inequalities faced by women and girls globally. Watson discussed the roots of her own feminism, while addressing the fact it’s an “unpopular word.”

“Apparently, [women’s expression is] seen as too strong, too aggressive, isolating and anti-men, unattractive even,” she said. More than 160 years after the first feminist conference at Seneca Falls, N.Y., Watson felt obliged to define the word: “For the record, feminism by definition is the belief that women and men should have equal rights and opportunities.” It remains an elusive goal, she said: “There is no one country in the world where all women can expect to receive these rights.” As if to underscore the reality of identifying as a feminist, hours after Watson’s speech, 4Chan hackers made headlines by threatening to release nude photos of the actress.

There’s a nice synchronicity in the fact that popular culture has become ground zero for activism, evident in last year’s backlash to Blurred Lines, Robin Thicke’s R&B party jam that sparked outrage for being “rapey” amid a larger debate about sexual assault on college campuses. It gave rise to the “Rewind & Reframe” campaign, in which young women aired grievances about music videos, campaigned for age ratings, and encouraged compulsory sex and relationship education in schools. Amid the fray, Lorde addressed the power of pop music, and how the Internet has inured people to explicit lyrics and behaviour: “There are a lot of shock tactics these days: people trying to outdo each other, which will probably culminate in two people f–king on stage at the Grammys.”

Against that backdrop, Moran’s story—of a fat, plain teenage girl who is confident and horny and has healthy sex adventures—is radical. “Teenage girls are going to do that anyway, so we’ve got a choice: We can either let them go out there and have scared, freaky, screwed-up sex based on the pornography that they’ve seen, or they can go out there and have joyful, amusing, consensual, informed sex,” Moran says. “And the only place they’re going to get that kind of information is from literature, because their parents aren’t going to tell them. Pornography’s not going to tell them.

“People of my generation forget that our teenage girls are in a world of free Internet pornography and they are on their school buses being shown really graphic stuff on mobile phones. This is where they’re getting their sex education.”

The market for raw, honest, unairbrushed female experience is reflected in the attention thrust on Lena Dunham, the 28-year-old feminist writer, actor and director behind Girls, an HBO program known for funny, solipsistic storylines and casual nudity, most of it involving Dunham defiantly shot in unflattering light. Appetite for what she has to say is reflected in a $3.5-million advance paid for her memoir, published this week: Not That Kind of Girl: A Young Woman Tells You What She’s “Learned.”

A similar ethic of female self-acceptance of the sort that skin-care company Dove harnessed in its ads is evident in the current top song on Billboard, Meghan Trainor’s All About That Bass: “I ain’t no size two,” Trainor sings, while trashing Barbie and Photoshop (“We know that s–t ain’t real, now make it stop”). Still, Trainor said this week that she refuses to be called a feminist.

Moran also wanted to provide an antidote to the immensely popular 50 Shades Of Grey, whose message disgusts her: “You have a young woman, a virgin, and then this powerful man comes along and wakes her up sexually and makes it all these things she doesn’t actually have any interest in doing,” she says. “This is ridiculous, that this is the template of female sexuality. But it’s nothing to do with her thoughts or her feelings or what she wants to do.”

In depicting female masturbation, Moran violates another cultural taboo she finds ridiculous—“especially in a world where American Pie has spawned eight films all based around a man putting his penis into a pie.” Sexual self-gratification is a form of female power; you can activate yourself, she says, noting that teenage girls need to have three hobbies: “Masturbation, long country walks, and revolution.”

The seeds for revolution exist in popular culture, says Moran. “It’s in movies, books, and the stories you read and the poetry and the songs and the things you wear and the websites you hang out at. You can go march for an issue, but culture marches forever.”

It’s not surprising that deconstructing popular culture has become a central tool in the new feminist arsenal, evident in the work of 30-year-old Anita Sarkeesian, a Toronto native known for cleverly exposing objectification of girls and women in gaming culture. Her YouTube videos, with hundreds of thousands of views, have taken on Ms. Pac-Man, the Manic Pixie Dream Girl meme, Smurfettes, and the lame way Lego is marketed to girls. Sarkseeian’s own experience reveals the pernicious online misogyny she wants to eradicate: she’s been threatened with rape and made the target of an online game: Beat Up Anita Sarkeesian. That’s only one example of how the Internet exists as a Möbius strip: enabling feminist activism and also its counterinsurgency, seen in online trolling, death threats, attacks on comment threats and the hashtag #womenagainstfeminism. “The comments on any article about feminism justify feminism,” British journalist Helen Lewis once tweeted.

Sarkeesian also has huge online support. When she set up a Kickstarter campaign for a new project with the goal of raising $6,000 earlier this year, she met it in less than 24 hours and went on to collect more than 25 times that.

Combating the overt sexualization of girls and young women in advertising and the media is one target of Spark Movement, a New York City-based online activist group that works with hundreds of young women aged 13 to 22, and 60 national organizations spanning the U.S., Canada, Britain and Indonesia. Founded in 2010, the organization already effected change: a 2012 campaign forced Seventeen to change its Photoshop policy and promise to “never change girls’ body or face shapes” when retouching images.

Fuelling mobilization is a backlash to the cultural myth that we live in a post-“girl power” world—that girls can do anything, says Melissa Campbell, Spark Movement’s program coordinator. “Then they get to science class and see teachers taking their male peers more seriously. Or they watch movies and see no girls that look like them on screen. They say, ‘If I can be anything, why are they treating me like this?’ ”

One answer is proposed by author Susan Douglas, who in 2010 coined the term “enlightened sexism” in the book of the same name. Douglas describes how “girl power” was reframed to mean that young women can be or do anything they want, as long as they conform to confining ideals around femininity, and don’t want too much. “It is a new, subtle, sneaky form of sexism that seems to accept—even celebrate —female achievements on the surface, but is really about repudiating feminism and keeping women, especially young women, in their place,” she writes. “Enlightened sexism insists that women have made plenty of progress because of feminism—indeed, that full equality has allegedly been achieved—so now it’s OK, even amusing, to resurrect sexist stereotypes of girls and women.”

She points to the explosion in makeover, matchmaking, modelling and reality shows where the emphasis is on plastic surgery, the obsession with babies and motherhood in celebrity journalism (creepy “baby bump patrol”), and a celebration of stay-at-home moms and “opting out” of the workforce. The culture is still extremely misogynist and exploitative, says 18-year-old Katy Ma, a freshman at Wellesley University in Massachusetts. “Society teaches girls from a young age that in order to be valued, they need to be desired by men—so when people criticize girls for being ‘vain’ or self-objectifying, it’s frustrating. They fail to recognize the root of the problem.” She recounts a radio interview with actress turned fashion designer and author Lauren Conrad in which the host asks Conrad: “What’s your favourite position?” “In a heartbeat she responds, ‘CEO,’ ” says Ma. “Snaps to that.”

Another Spark Movement project, #DoodleUs, addressed female representation in the culture, starting with Google Doodles. “The issue wasn’t just Google Doodles,” says Ma, who was involved. “It was also the way we learn and teach history—how the accomplishments of women and people of colour are often diminished, or worse, forgotten entirely.” Now Ma is part of the team creating Field Trip, a travel app developed by Google that identifies historical locations. This iteration, which will note where women have made important contributions to society historically, will soon launch in the U.S. with plans to go global next year.

Spark Movement has a current project to draw attention to cosmetic face-whitening ad campaigns. Another series, Black Women Create, focuses on writers and directors to demystify the backstage process, says Joneka Percentie, a 19-year-old university student. “Some popular feminist blogs are very exclusive and don’t look critically at obvious intersections of race or sexuality,” says Percentie. “It’s clear that it’s usually run by white, heterosexual middle-aged women.” Evans also criticizes Moran for not taking on the cause of women of colour. “She’s a great writer and inspirational. But she consistently refuses to mention anything with race. I think that’s damaging.”

The new activist wave actively rejects the stereotypes harnessed to marginalize feminism in the past. “My story of female empowerment, if you can call it that, comes from rejecting everything that the feminist who works at the bookstore on Portlandia would believe in,” 29-year-old Sophia Amoruso, the entrepreneur behind Nasty Girl Vintage, a site now worth more than $100 million, told Fast Company this year. Her recently published book, #GIRLBOSS, a hybrid business bible and memoir with one chapter titled: “Money looks better in the bank than on your feet,” provides a Millennial response to Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In. “There’s a difference between making compromises and being compromised, which a lot of women do let happen,” she writes.

The new activism is also more inclusive. “Ultimately, feminism is good for men, too—a world where boys don’t feel pressured to hide emotion and act macho all the time,” says Svitak. Emma Watson also touched on what the failure of feminism means to men: “Men don’t have the benefits of gender equality either.”

Spark Movement’s Campbell, 25, is encouraged by how girls become aware of these systems and look for ways around them. “Girls pose a threat,” she says. “People are so scared of teen girls—they treat them terribly, even though they’re so much more imaginative in many ways than adults are. They haven’t been ground into dust yet. That’s what makes them so dangerous.”

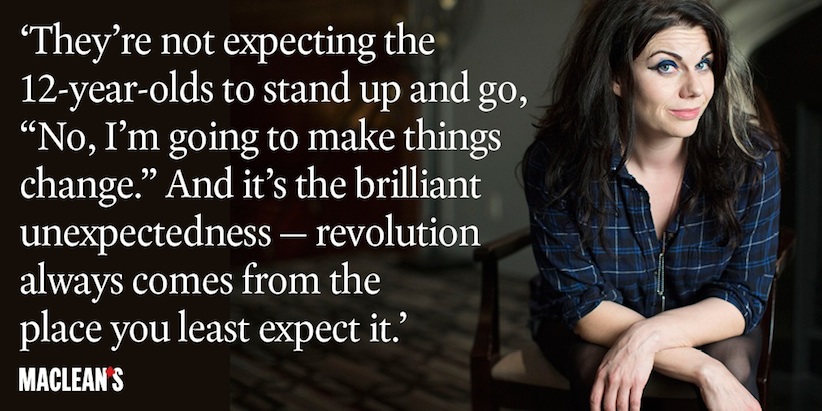

Moran agrees. “No one expects it from a 13-year-old girl. They think you only become a feminist when you’re, like, 26 or 35. They’re not expecting the 12-year-olds to stand up and go, ‘No, I’m going to make things change.’ And it’s the brilliant unexpectedness—revolution always comes from the place you least expect it.”

Moran does express concern over growing cynicism in the last year or so, particularly on Twitter: younger left-wing activists are attacking Lena Dunham for not doing more, she says. “They’re saying, ‘She’s done all this for female representation but why doesn’t she do all this other stuff as well?’ It’s basically saying: ‘The revolution isn’t perfect, so I don’t believe in any of it.’ And you endanger your soul, particularly at that age, if you become cynical, because you’re not believing that things will get better. Which means you think that you’re not going to get better. Because cynicism is just fear. If our young people are scared to believe in things changing, then we’re all in a lot of trouble.”

Amy Poehler, co-founder of the online forum Smart Girls at the Party: Change the World by Being Yourself, expresses similar sentiments. She has said her project was prompted by the cultural perception that it’s cool to be unmotivated and indifferent: “Our culture can get so snarky and ironic sometimes and we kind of wanted Smart Girls to celebrate the opposite of that.” Moran says she took a great deal of time in How to Build a Girl to explain how tiny life becomes if you’re cynical. “It’s just not that much fun,” she says. “Be the person who runs into the room and goes, ‘Oh my God, something amazing has happened!’ Because even if sometimes you’re proven to be wrong, at least you’ve still had the thrill, at least you still believe in possibility. You should always be ready to be wrong.”

Campbell believes it’s time to stop telling girls what to do: “One of the most radical and transformative things we can do if we’re trying to build a better world for girls—just trust girls. Let girls take risks, let them make mistakes, then help them if they do.”

The way to build a better girl, it’s clear, is to let her to do it herself.