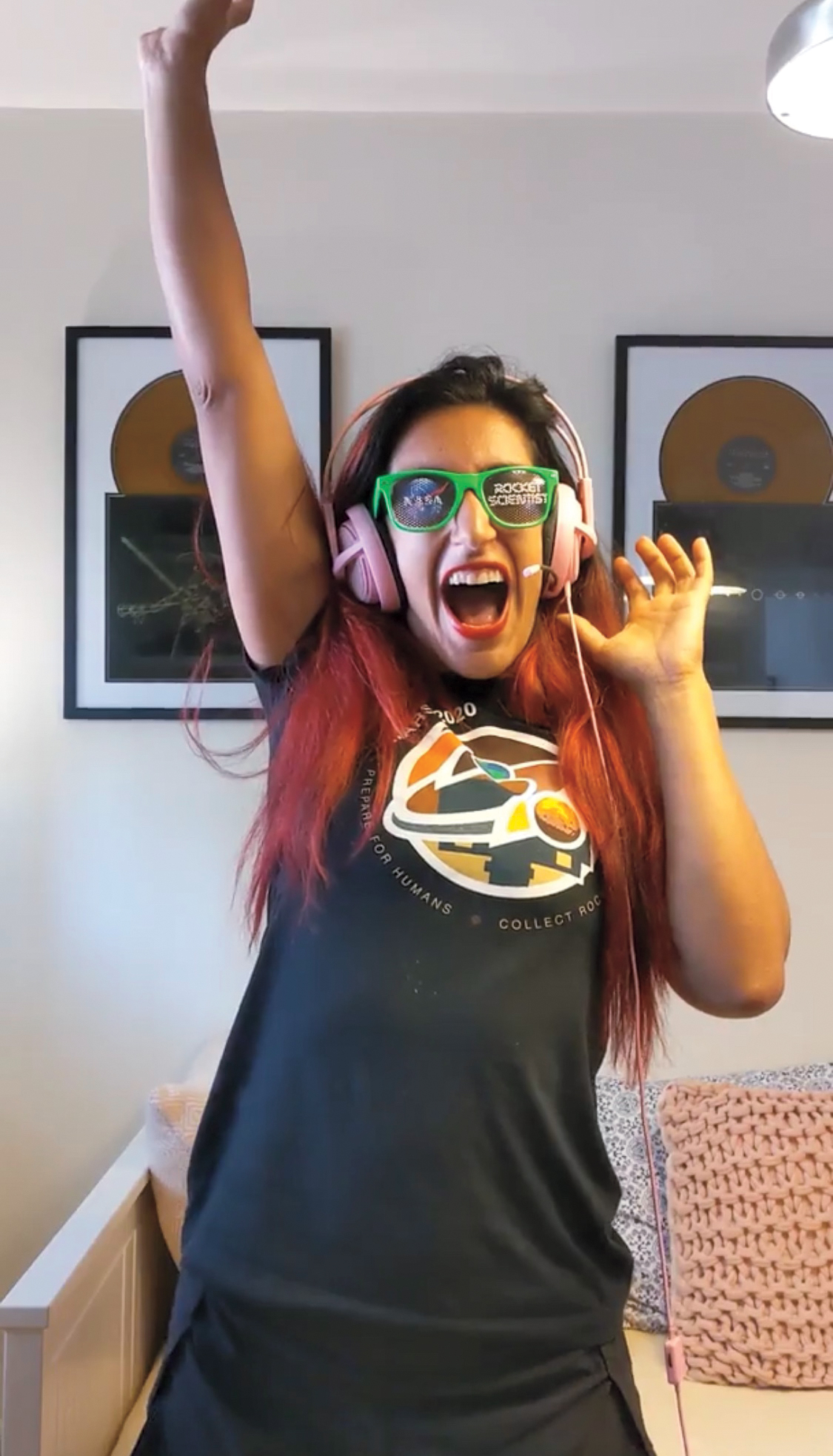

A NASA engineer on Mars and life in the universe: ‘It would be very lonely if it were only us’

Farah Alibay’s fixation with knowing how things work led to a career pondering life’s biggest questions

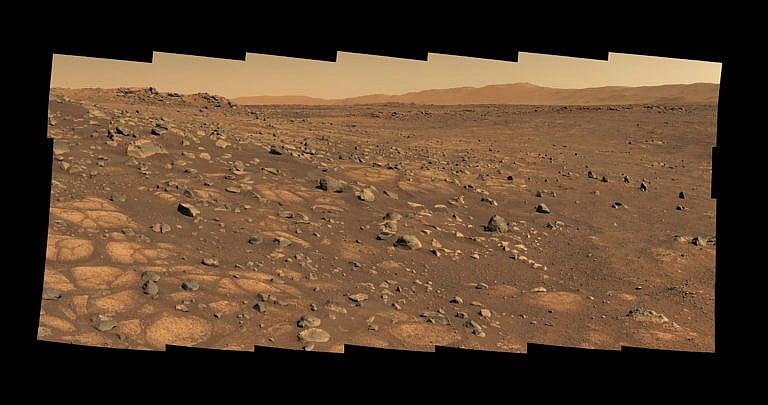

Alibay programmed NASA’s Perseverance rover to visit several sites on Mars, including the Jezero Crater, a dried-up lake bed (Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/MSSS)

Share

I operate Perseverance, NASA’s rover on the surface of Mars—we have a team of about 60 people. We work on local Mars time, or LMST. A Martian day, or sol, is 24 hours and 40 minutes, so my shift starts 40 minutes later each day. We’re not at our desks with joysticks driving the rover like a video game; we prepare a piece of code that gives Perseverance a plan down to the second. The rover follows our instructions and sends us information every night. The scientists observe the images that come back and decide where they want to explore next. My team and I program the rover to go there. It’s a new adventure every day.

Recently, we landed in Jezero Crater, an ancient, dried-up lake bed that was fed by an ancient river. These are features we haven’t seen elsewhere on Mars yet, and eventually we’ll explore the delta of that river. Through the eyes and ears of the rover cameras and microphones, I’m one of the first few humans ever to see that place on Mars. Isn’t that incredible?

I remember seeing the movie Apollo 13 when I was nine, on VHS, with my family in our living room. My brother, who was six or seven at that time, was really interested in space. But while we were watching the movie, he got worried about what was going to happen to the astronauts, so we had to fast-forward to the end to show him that they made it back to Earth. After that, he was done with space, because he thought it was too dangerous. But I became intrigued.

READ: China’s mission to Mars opens a new phase of the space race

There was a scene where they brought out all the things that were in the spacecraft and said, “These are the parts we have on board.” They had to figure out how to save the astronauts with what they had. What was striking to me was watching all of these serious people taping things together, working together, trying to figure it out. And you see that in movies often, where everyone works together to find a solution. But this actually happened—the film was based on the aborted Apollo 13 lunar mission in 1970.

That scene is pretty representative of what we do as aerospace engineers, because once we launch, we can’t fix anything. Once the rover’s in space, all we can do are software updates. For example, the Mars Exploration Rover team switched to sometimes driving Opportunity backwards during their mission to reduce wear and tear on its motors. It’s never a question of whether we’ll just give up. It’s, “What do we do next? We’ll figure this out.”

RELATED: Canada’s best university engineering programs: 2022 rankings

As a teenager, I was always taking apart things like old radios or remote controls. We never had contractors in the house because my dad would always be the one fixing things. He was an electrical engineer and when he installed the wiring around the house, I’d be handing him tools. I’d ask, “How does this work?” and he’d take the time to teach me.

I was good at school and people would tell me: “You should be a teacher or a doctor.” It wasn’t until I was 16 that I realized that I liked space and I liked tinkering and I’m good at math and physics. I figured, there’s a job for that, right?

It was not an easy path. I failed a million times. I didn’t think I belonged. But I couldn’t imagine doing anything else. When I finished my program at Cambridge University, I had a job offer to work with planes, which I turned down. When you work in an established field like aviation, your contribution might be two or three per cent of an increase in efficiency, which is huge. But when you work in aerospace, you’re writing the textbooks.

Perseverance has some pretty lofty goals; we’re looking for signs of ancient life on Mars. We think the Earth and Mars looked similar about two billion years ago—Mars had an atmosphere, liquid water and a magnetosphere. Our hypothesis is, if there was life on Earth back then, could there have been life on Mars? And that’s what Perseverance is doing—looking for samples that might help us answer an existential question we’ve asked ourselves for hundreds of years: where do we come from, and why are we this way and not another way? I spend my days trying to understand what our place in the universe is.

MORE: ‘Green technology’ is fine, but to really save the planet we need to shop less

Mars’s gravity is one-third that of Earth’s, and it only has one per cent of Earth’s atmosphere, so the blades of the helicopter Ingenuity have to spin really fast. The helicopter uses up a lot of its battery energy just surviving the Martian night and needs to recharge, so we can’t fly in the morning. Ingenuity’s first flight went up five metres, hovered for 30 seconds and then landed. That was it. But the flights are getting more complex each day. Now we’re flying faster and longer distances and landing in different locations. We’re pushing the boundaries with every flight we perform.

Half of what we do is Earth exploration and observation. Mars used to look like Earth and now it’s horrible—it gets really cold and there are a lot of strange winds. There’s also radiation because it doesn’t have an atmosphere anymore. Looking at it makes you realize how unique and fragile our planet is and makes you cherish it even more. Most of the people I work with are environmentalists and care a great deal about climate change.

We’ve also been looking for exoplanets, planets that might look like Earth that are outside of our solar system. Understanding what the differences are between all these planets might help us find one that is habitable and then we could have a chance of finding life. A lot of the research that’s being done at NASA right now focuses on this concept that we’re not alone out here. It would be such a weird statistical oddity if we were. The universe is so big. There are so many solar systems. Surely there’s going to be something else out there. It would be very lonely if it were only us.

—As told to Jessica Lee

This article appears in print in the October 2021 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “The meaning of Mars.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.