Facebook watching: Nine hours in the world of Facebook Live

Despite the headlines, Facebook Live is mostly banal. So what does the social network want with all our boring videos?

Share

In January, a group of four teenagers in Chicago kidnapped and abused a mentally disabled man. They broadcast the entire awful incident live—via Facebook.

Later that month, a 14-year old girl in Miami took her own life while also broadcasting on Facebook Live. A friend who reportedly saw the video called police.

Then, in April, Steve Stephens recorded himself shooting and killing an innocent elderly man, Robert Godwin Sr., in Cleveland. Stephens did not actually broadcast the murder live on Facebook, but uploaded it there after the fact. Still, initial reports that he had filmed it live became part of the narrative nonetheless. Stephens eventually killed himself (away from cameras).

Less than two weeks later, a 22-year old Thai man named Wuttisan Wongtalay did broadcast via Facebook Live as he hanged his 11-month old daughter, and then took his own life. The girl’s mother, who was scrolling through Facebook at the time, saw it happening and alerted authorities.

Faced with public backlashes following these horrific news stories, and in an attempt to refocus the narrative surrounding its live broadcasting feature, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg recently announced the company will add 3,000 more staff members to respond to user content alerts, and take action should anything gruesome occur.

Of course, day to day, Facebook Live is not replete with those sorts of videos; most feature far more benign subject matter. So, what will those 3,000 extra Facebook souls see, if not disturbing images?

READ MORE: The case for pressing pause on Facebook Live

At any time on Facebook, hundreds, maybe thousands, are inviting the world to watch them in real time. If they’re not doing something that catches the attention of Facebook’s content control managers, how are they using Facebook Live? Or, perhaps, how is it using them?

Recently, I spent a day watching nine hours worth of Facebook Live videos, trying to find out. It’s not difficult to do — Facebook created a global map upon which tiny blue dots light up whenever someone begins broadcasting live; all you have to do to watch is click the dot. And although I discovered the content of most Facebook Live videos is overwhelmingly banal, it raises the question: what does Facebook really want with all our boring videos?

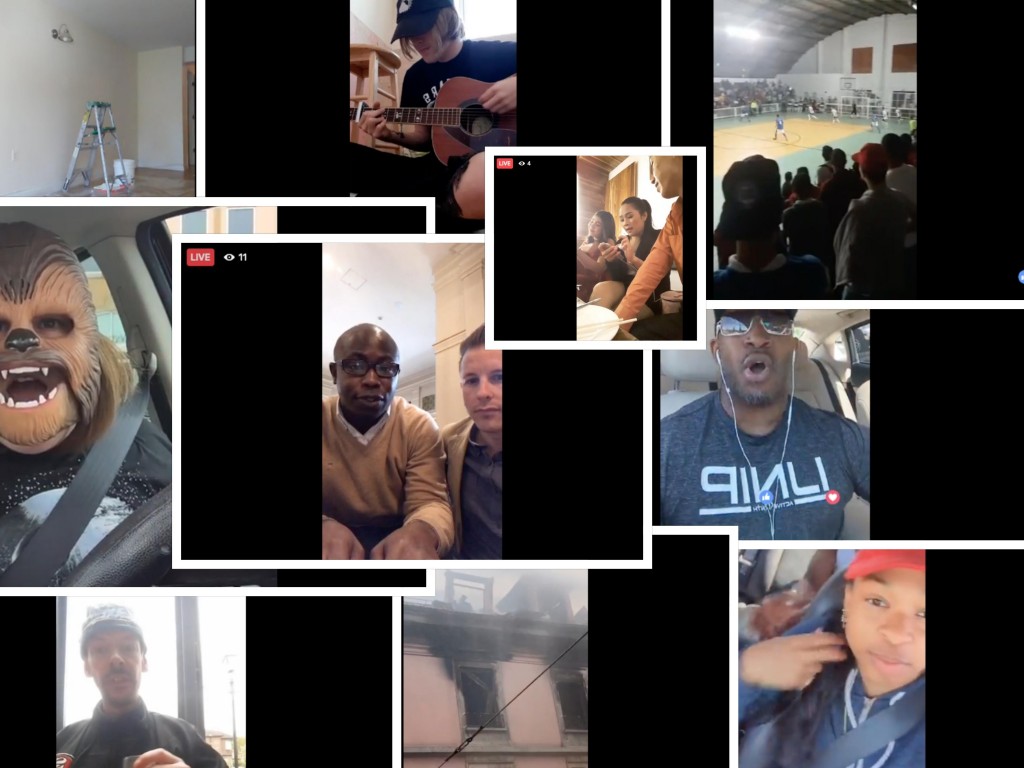

Over the course of my nine hours watching well over a hundred Facebook Live videos, I watched: boys in Pakistan playing cricket; a bartender mixing drinks at a cocktail competition in Spain; a martial arts class in Japan; a family eating dinner at a restaurant in South Korea; a woman in Thailand dancing to Justin Timberlake’s “Can’t Stop the Feeling”; a young man driving a truck down Highway 401 in Ontario while listening to music; a dog giving birth to puppies in Edmonton; and a man in the Bronx who, before exiting the frame for a while, had been painting a wall white, leaving behind a literal live feed of paint beginning to dry.

Mixed in were videos of more significance—or, at least, more news.

Given that I was watching Facebook Live on the day following Emmanuel Macron’s election as France’s new president, I also saw a live feed of left-wing protesters gathering to hear speeches before they marched through the streets of Paris. A short time later, New York Times columnist Roger Cohen was also broadcasting live from Paris, as he chatted with voters about the previous day’s election result. About 20 minutes later, I briefly watched U.K. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn speak live at the University of Warwick.

At one point, I checked in on something called DreamHack Counter-Strike Live, a stream of a gaming competition that was being watched simultaneously by a theatre full of people in real life, and by approximately 1,300 more online. Even more joined me in watching a small-time American right-wing talking head, Harlan Hill, bloviate live in front of a laptop on a channel run by Dennis Michael Lynch Media. Somewhere north of 2,000 watched that—a viewership figure not all that uncommon in the increasingly internet-centric, niche right wing media world—just a smattering of those who have taken advantage of Facebook’s free platform and reach to create media channels.

That kind of usage is in line with Facebook’s plan. “Historically, Facebook has seen itself as a distribution platform, or almost a social utility, comparable to email or phone or text,” says Antonio García Martínez, author of Chaos Monkeys: Obscene Fortune and Random Failure in Silicon Valley, who served as an ads product manager at Facebook for several years.

That idea sits in the subtext of a post by Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, published the day Facebook Live became available to all. “When you interact live, you feel connected in a more personal way,” he wrote in April 2016. Facebook Live is “a big shift in how we communicate, and it’s going to create new opportunities for people to come together.”

For awhile, this shift seemed not only true, but also positive – if not downright fun. Two days after Zuckerberg’s post, BuzzFeed live-streamed two employees gradually wrapping increasing numbers of elastic bands around the centre of a watermelon until it exploded. That video has been watched over 11 million times.

A month later, Facebook Live scored an even bigger viral moment, when Candace Payne excitedly broadcast from a parking lot that she’d bought a new toy—not for her kids, but for herself. It was a Chewbacca mask that emitted the Wookiee’s tell-tale call every time Payne opened her mouth to speak or laugh. It was an instant sensation. The “Chewbacca Mom” video has been seen over 160 million times—though many of those views were not live.

Then, in July 2016, Diamond Reynolds used Facebook Live to broadcast the moments after a police officer fatally shot her boyfriend, Philando Castile, after the pair had been pulled over. Through shocking, the existence of the video evidence was considered overall to be positive: a new kind of transparency on police action in the U.S.

Then came 2017, and with it, a different kind of horror.

Still, the way Facebook Live has been adopted for good and ill speaks—rather darkly—to Facebook’s success in positioning itself as a public utility.

READ MORE: Should Facebook tell you more about political ads?

“The reality is that any technology… once it gets used by the sort of criminal class, then you know it’s for real. Your product has succeeded, you’ve gone from being some consumer product, capital letter T-M, to a utility that everyone uses,” García Martínez says. “It’s embarrassing as hell, but at the end of the day, that livestream is a success as a product. I’m having this incredible emotional moment and avenging myself in some criminal way, and if my first stop is ‘oh, let’s use Facebook Live,’–like, that’s the way I declare it to the world—I mean, y’know, you’ve made it as a product.”

Unless it has been promoted by a media outlet or happens to have gone viral somehow, only a handful of people are watching the majority of Facebook Live videos in real time. Even after they’re posted to the videographer’s Facebook wall, viewership will likely remain very low.

In some instances, videos that were at one time live are deleted by their creators; unless you saw the livestream, you’ll never see that video. Most of us simply don’t have time to waste on Facebook Live videos, live or on replay.

Still, someone—or something—has to monitor this stuff. Hence, those 3,000 new Facebook hires “to review the millions of reports we get every week, and improve the process for doing it quickly,” as Zuckerberg wrote. The new hires join a team of 4,500 content monitors.

There are two points we should consider as Facebook brings on more people, says García Martínez. One is that even with more eyeballs, Facebook’s human staff can’t see everything; the second is that, for a company of Facebook’s size, 3,000 is quite a few.

“Facebook could hire 300,000 people and it wouldn’t be enough to look at every video. There’s absolutely no way a human is looking at every video,” says García Martínez, whose ads team was also required to monitor content to ensure it did not violate Facebook’s terms. For live video, that includes some types of nudity, hate speech, and violent or graphic content.

On Sunday, the Guardian reported on leaked rules for moderators at Facebook. “Videos of violent deaths, while marked as disturbing, do not always have to be deleted because they can help create awareness of issues such as mental illness,” the Guardian reported, based on the content of the leaked documents. Those documents also show that Facebook will “allow people to livestream attempts to self-harm because it ‘doesn’t want to censor or punish people in distress,’” the Guardian said.

READ MORE: The problem with Facebook’s plan to teach you how to read news

Still, that does not mean these videos aren’t being reported and assessed. Facebook’s 3,000 new hires are not merely a public relations exercise, García Martínez says. Their presence is a way to expand Facebook’s whack-a-mole approach to offensive or disturbing material reported by users. “If you imagine it being a funnel and millions, if not billions, of videos are going into the funnel, [the extra employees] sort of expands the base of the funnel in terms of how many videos they can possibly look at or how many videos they can take a closer look at.”

And though the number of new hires may seem insignificant against the sheer volume of video, they are still meaningful, he says.

“Facebook isn’t actually that big a company when you compare it to Google or Microsoft, and these are all going to be operations people which Facebook doesn’t like to manage. So to them, hiring 3,000 ops people is actually kind of a big step,” says García Martínez. “I think it should be taken seriously.”

Perhaps the best way to understand what role Facebook could play in our future is to not think of it as a social media company at all—or even a media company—but instead as a company that develops artificial intelligence. What becomes immediately clear after watching a litany of Facebook Live videos is Facebook’s real “connection” is not really between two people, but between one person and a screen. The humans who use Facebook Live are not teaching each other about humanity as much as they are teaching a computer program about it.

Facebook, like many others, is hard at work developing machine learning, which involves feeding computers huge quantities of information so they can see and ‘learn’ patterns. This is how computers are increasingly carrying out image analysis, wherein a computer program will not only be able to distinguish between objects in a photo or scene, but identify each separate item.

To do that, researchers need to create something called “deep convolutional neural networks” that can automatically deduce—hence, machine learning — “patterns from millions of annotated examples, and having seen a sufficient number of such examples start to generalize to novel images.” It’s a kind of layered network that is trained to answer ever more abstract yes-no questions as it examines an image—starting with something as simple as whether or not there IS an object in an image at all—to eventually, after some refinement, picking out and identifying each image’s disparate parts.

MORE: An interview with Geoffrey Hinton, the godfather of ‘neural network’ AI

In April 2016, the head of Facebook’s Applied Machine Learning, Joaquin Quiñonero Candela, told Popular Science the company was still trying to get its algorithms to identify where images are in photos—something called “semantic segmentation.” That is, the program doesn’t just know that an item is present in the image, but how it is oriented.

In February, Candela gave an update: Facebook has developed a way for users to search for a photo simply by typing in a description of what’s in it. This advancement, Candela wrote, helps with things like image description for the visually impaired. “Until recently, these captions described only the objects in the photo,” Candela wrote. As of the update, Facebook has added twelve actions “so image descriptions will now include things like ‘people walking,’ ‘people dancing,’ ‘people riding horses,’ ‘people playing instruments,’ and more.”

How did they do it?

Facebook built on its Lumos platform, a computer vision platform for the visually impaired. They then curated 130,000 public Facebook photos that included people, had “human annotators” write one-line descriptions and then “leveraged these annotations to build a machine-learning model that can seamlessly infer actions of people in photos.”

Facebook has already started to apply the same thinking to video in the hopes of perfecting it there, too. As with live broadcasting, Facebook is not at the forefront of this kind of thing; Google Photos has had something similar for a while, but it lacks the deep-rooted veins of a billion-user social network.

The day a machine watches you in much the same way a human can is tantalizingly—or worryingly—close, depending on your perspective.

A few weeks after Facebook announced its Lumos update, Candela spoke with Steven Levy, the editor of Backchannel. He told Levy there are four areas in which A.I. is applicable: vision, language, speech, and camera effects. “All of those, he says, will lead to a ‘content understanding engine,’ ” Levy wrote. “By figuring out how to actually know what content means, Facebook intends to detect subtle intent from comments, extract nuance from the spoken word, identify faces of your friends that fleetingly appear in videos, and interpret your expressions and map them onto avatars in virtual reality sessions.”

In March, Google announced it had found a way to teach its computers to interpret video content without manual tagging. Google can also pinpoint when that content appears in the video. “For example, searching for ‘tiger’ would find all precise shots containing tigers across a video collection in Google Cloud Storage,” Google said. And in November, a team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology announced they’d created an A.I. system that, when given a still image from a video, could predict what might happen in the next few frames.

Could A.I. interpret video as it watches thousands of live videos in real-time?

Yes, says Sanja Fidler, an assistant professor at the University of Toronto who works in the field of computer vision. Someday—and probably soon.

“In the end, if you have a lot of labelled data, you can start training these algorithms to do this for you,” she says. A program may be able to recognize, for instance, whether someone is at the beach, or in an urban environment, or what store someone is standing in. “You could start reading this from the actual videos. You can start analyzing the behaviour of people, which is not what you’re getting from images.”

An algorithm is already at work recognizing disturbing content, perhaps explaining why I saw none in my one-day experiment. No doubt, questions of content allowance—what qualifies as “pornography,” for instance—will arise, just as they did when Facebook removed the Pulitzer Prize-winning 1972 photo of a young naked Vietnamese girl fleeing an American napalm drop.

Just as likely, however, will be questions about behavioural analysis.

When a Facebook Live broadcast is over, “the video will be published to the Page or profile so that fans and friends who missed it can watch at a later time,” Facebook says in its FAQ page. “The broadcaster can remove the video post at any time, just like any other post.”

But just because something has disappeared from a user’s Facebook wall—just because nobody will ever see it—doesn’t mean it’s gone. The control we feel over the content we create is somewhat deceiving. Anyone who has ever downloaded their Facebook history knows that, no matter what you’ve chosen to delete or make private, Facebook remembers.

“They are storing this data, they are processing this data,” Fidler says.

Facebook warns its users of this fact in its terms of service, likening the deletion process to “emptying the recycling bin on a computer… the removed content may persist in backup copies for a reasonable amount of time.”

READ MORE: The dark irony behind Facebook’s fake news problem

I asked Facebook whether it permanently stores videos, or whether they are deleted permanently once they’re removed from a user’s wall. I asked Facebook what data it collects from Facebook Live videos, or from accounts belonging those watching. And I asked Facebook how it uses the data collected from a Live video. Facebook answered all three questions by providing a link to its data privacy page.

There is a push in Europe to force Facebook to change the way it collects and shares. Last week, both French and Dutch officials said the site “had not provided people in their countries with sufficient control over how their details are used,” the New York Times reported. France fined Facebook €150,000 ($227,000) for failing to meet privacy protection rules in that country. However, in just over a year, Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation will go into effect, and, under those new rules, tech companies could be fined as much as €20 million ($30.3 million), or four per cent of company revenue—whichever is higher.

Which means, in Europe—unless Facebook finds a way around the new rules—shareable personal details could become very limited indeed. In the U.S., there is an attempt to extend privacy rules that now apply to internet service providers to Facebook and Google, meaning they would need user permission before sharing things like browsing history with advertisers. However, that bill has a distance to go before passing.

In the meantime, Facebook forges ahead, and the consequences of its technological prowess, coupled with its global reach could be considerable.

Currently, via your online behaviour, Facebook understands what you’re like on the internet. It knows the websites you visit, the pages you like, your political affiliation, where you live. Via the photos you share and the posts you write, it probably knows a fair bit about how you spend your time offline, too. Facebook might know where you like to go on vacation, and maybe where you work. It probably knows which friends on your list you actually spend time with and talk to. It might even know what your children look like, and what park they visit.

Live video could tell Facebook a lot more.

What happens when Facebook Live’s built-in video scanning A.I. can tell what brand of sofa you own and clothing you wear? Or whether you’re pregnant?

Better yet, what happens when A.I. understands not just the topic of live human conversation, but its content? Most of that data might still not have what García Martínez calls “commercial value.” Your drunken party conversation or lip-sync to Justin Timberlake might not tell Facebook anything more about you than it already knows. But live video may be more telling of human intent, emotion, or desire than anything any of us would write in a post or message, or reveal in a photograph. At the moment, for instance, when Facebook’s A.I. examines a video, it can’t judge honesty; it cannot distinguish whether your rant about a product or political party is sincere or mocking, or whether your smile in a photo is genuine. An algorithm cannot yet scan live video footage and tell if we’re lying. What happens when it can?

“How has it come to this? How has it come to this? It’s twenty past six on a Monday night, and I’m in the pub and I’m pissed.”

A man named Alex, whose public profile page says he lives in Scarborough, North Yorkshire, U.K., is indeed sitting in a pub on a Monday evening. He lounges in front of a window, wearing a toque. He occasionally takes a drag from his vaper. Alex chats idly about getting “a vindaloo later.”

At this point, he has one viewer: me.

“Facebook Live, what a fantastic invention that was,” Alex says. “So, who are you, one viewer? Who is it?”

Alex picks up the phone. The camera faces the skylight above him, he is cast in silhouette. “Who is it? Who is it? I don’t know how to use this, I haven’t got a clue.”

I sit silently at my computer in Toronto, watching. It is just Alex and I. In some ways, this is just like television—a camera over there feeding to a screen over here—just taken to a banal extreme. But there is one crucial difference: most of the time, Alex doesn’t look directly at the camera, and thus not directly at me; instead, he looks at his phone’s display—the mirrored reflection of himself.

Moments pass. Eventually, some people listed as Alex’s friends on his profile are alerted to his livestream and start to leave comments; questions about his car and the music playing in the background.

In all, Alex is live for just under a half hour, after which he starts a new livestream.

What did I learn about Alex in those few minutes? He mentioned a few details about his life beyond the pub, including a long diatribe about what menu items he enjoys at a local Indian restaurant that also allows customers to bring their own alcohol. Inconsequential details I will soon forget.

In a near future, when Facebook’s machine learning is perfected, it may learn the same few things about Alex that I did, understand the same words and context, and, like me, internalize them for later use. Unlike me, Facebook won’t forget.