Why we needn’t be so mindful of what we eat

The director of the Cornell University food and brand lab on how to eat less and enjoy it more.

Share

Psychologist Brian Wansink is the director of the Cornell University food and brand lab and an authority on eating behaviour. His book, Slim by Design: Mindless Eating Solutions for Everyday Life, calls for a societal overhaul of how we approach food and eating.

Q: Your subtitle is “mindless eating solutions.” Shouldn’t we be mindful of what we eat?

A: In an ideal world, yes. In the real world, it works for five to 10 per cent of us. Instead, we need to set up our eating environment so that, mindlessly, we eat less and enjoy it more.

Q: You propose people need to improve their “food radius.” What is that?

A: Most food choices happen within five miles of where we live—our home, two or three most frequented restaurants, our main grocery store, our work, our kids’ schools. If we tackle that, we’ll not only eat better but have a positive effect on our families, our neighbours as well as the 80 per cent of people who don’t care what or how they eat.

Q: You write that people’s kitchen counters can reveal whether they’re fat or thin.

A: Yes, we found we could predict weight by what foods are visible. If there’s a box of cookies or bag of potato chips, occupants weighed nine pounds more than the norm. If cereal was visible, they weighed 21 lb. more. Any soft drink—even one can of diet cola—and they weighed 25 lb. more. If they had a fruit bowl, on the other hand, they weighed eight pounds less.

Q: You write that if food is inaccessible, people won’t eat it and you even advise people wrap their ice cream in foil. Why not veto ice cream to begin with?

A: Having it available but inaccessible is how some people have to do it. Sterilizing your kitchen of tempting food is going to backfire—you’ll eat it somewhere else. People who are problem snackers should have one cupboard—up high, way low, in the basement. You’ll also need something for kids; it can’t always be carrot sticks. The lab was commissioned to advise a notable gossip columnist who worked 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. She said her kitchen wasn’t the problem; there was no food in it. But that was her problem; when she’s hungry she had to do something drastic, like order an entire takeout meal.

Q: You recommend people use smaller plates and glasses to fool the eye and stomach.

A: You don’t want plates smaller than nine inches; you’ll know you’re deluding yourself. We also found changing a serving scoop from two ounces to three ounces increased the amount of ice cream served by 14 per cent. People didn’t gauge ice cream served; they gauged scoops. Now everyone in my lab is using tablespoons to serve everything.

Q: You also recommend coloured plates.

A: We found it isn’t the colour, it’s the contrast between the plate and what you’re serving that matters. When you serve white pasta on a white plate, you’ll serve 18 per cent more than white pasta served on a darker plate.

Q: You’ve also observed thin people navigate buffets differently.

A: People say you can’t go to a buffet and not overeat. At any buffet you find one-third of people are skinny. So what do they do? We found six things: they sat about 16 feet farther from food; they were three times as likely to face away from food; 71 per cent of thin people scouted the food, walking around before picking up a plate. Conversely, 73 per cent of overweight people did the opposite: they took more items because they weren’t as selective.

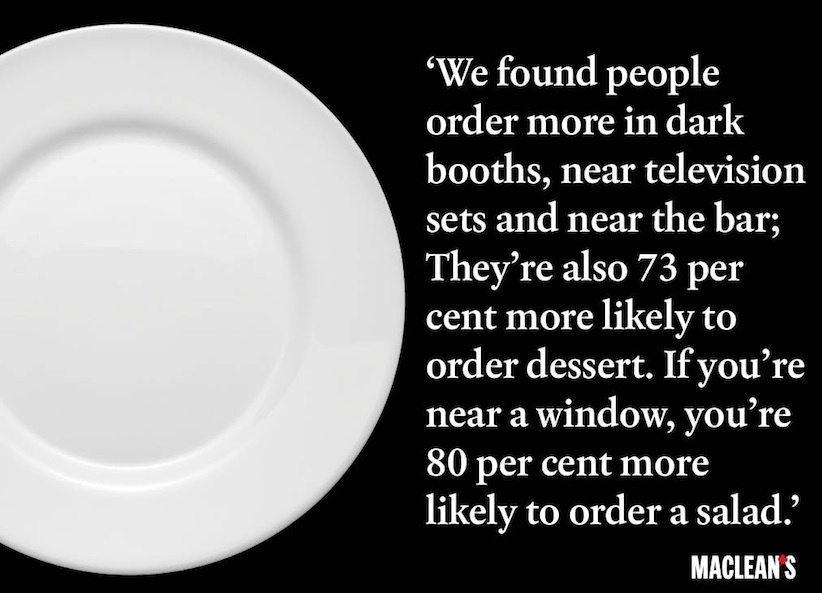

Q: You’ve done extensive studies mapping out restaurant “fat tables.” Where are they?

A: We found people order more in dark booths, near television sets and near the bar; They’re also 73 per cent more likely to order dessert. If you’re near a window, you’re 80 per cent more likely to order a salad. It could be that sitting next to a window cues the mind to freshness; in a back booth, it’s out-of-control indulgence.

Q: To what extent is this a chicken-and-egg situation, in which people who feel healthier and are thinner want a more prominent place—or are they given one?

A: We don’t know. But why debate causality when the couple behind you just took that [high table] next to the window?

Q: You write about how menus are creatively scripted to make us eat more.

A: Menus guide us to whatever items are coloured, bold, boxed. It biases us; the first item is more likely to be taken than 35th item. Secondly, the words used create biased expectations—to the point that something having a hint of vanilla or toasted coconut will make us spend 15 per cent more. We also found “crispy” comes with 102 more calories than something that doesn’t; fresh has fewer calories.

Q: You’re a fan of doggie bags, yet note few people ask for them.

A: Only 20 per cent of North Americans with leftover food do. Part of the reason is the “endowment effect”—once we own something we don’t want to give it up, even to be taken home. So we need to commit to taking it home ahead of time.

Q: How should people navigate grocery stores for more healthful results?

A: The first things we see in grocery stores, we’re more likely to take. We start with an empty grocery cart and nature abhors a vacuum. Luckily, the first thing most people see is produce. The problem is aisle two, which is usually unhealthy. So you have to shop healthier parts of store—produce, meat, whole grain aisle—not follow numbered aisles.

Q: You make a similar point about how people fill trays in cafeterias.

A: The first thing a person picks up is a “trigger food” that influences other choices. If we give a person an apple, they behave themselves; if they get a cookie, everything else is indulgent.

Q: You recommend adults make their own lunch for work because it’s healthier. But you suggest kids buy lunch at school. Why?

A: When we make lunches for other people, we think of it more as an indulgence but we hold the reins back on ourselves. When I make lunches for my kids, I give them things I’d never think to give myself. It’s a way to show I love them.

Q: What role does processed food play in weight gain—the fact it makes people eat a lot more to get a flavour hit?

A: It’s not that processed food is inherently inferior. It’s that it’s targeted to the lowest common denominator in terms of taste. Hamburger Helper is my comfort food; every time I’m in charge of dinner that’s what we have. But I’ll add vegetables, put in better meat; it’s still processed but made according to [my] directions, not General Mills’.

Q: That’s shocking. Isn’t celery your comfort food?

A: [Laughs] I grew up in a lower-middle-class family in the Midwest; casseroles were big.

Q: What is the role of class and wealth in the fat-thin divide? You write that people eat more when they buy in bulk—but that’s what you do if you’re trying to save money.

A: There’s not much we can do about income disparities. We can give people tips and suggestions. I’m currently working on a project with Cornell’s medical school helping low-income people eat better for less.

Q: How important is knowing how to cook?

A: It opens options—you don’t order pizza. Everybody is within seven dinners of being a capable cook. Are the meals going to be great? No. But the feeling of empowerment is dramatic.

Q: You write that employers are moving toward monitoring weight so they can offer benefits for thin employees.

A: Having employees sign “health contracts” certainly can be an approach smart companies could take. If they believed they could save on insurance or co-pay they become very interested. We’re currently working with a big company in Japan who want to do it not by weight or BMI but by waist circumference; I think it’s a terrible measurement.

Q: What have you learned over 25 years?

A: Almost every person, when we show them how they’re influenced, say, “[That] wouldn’t influence me.” They think they’re smarter than a bowl, smarter than a serving spoon. It’s amusing. Even with experts, nutrition experts, they say, “I know better.” But look at data. Show bartenders [that] they serve 30 per cent more liquor in short, wide tumblers than tall highball glasses, they deny it. We all think we’re uniquely unaffected by these things.

Q: How did we end up with mindless eating, constant snacking, and jumbo-sizing?

A: In 1960, North Americans spent 24 per cent of our income on food; now it’s six per cent. We have 500 flavours of potato chips sold at office supply stores and gas stations. This has created a new norm: it’s not weird to take a bottle of pop into a meeting; it’s not weird to take a snack break the way we used to take smoking breaks. A few years ago I lived in Paris where snacking is gauche. I spoke to a woman who said she was taught snacking is what lower-class people do. Holy cow! That’s indoctrination. We sure don’t have that norm here.