The power of paying it backward

Jillian Horton remembers one of her most influential teachers and friend, Michael Groden, and the small creative gambles he made possible

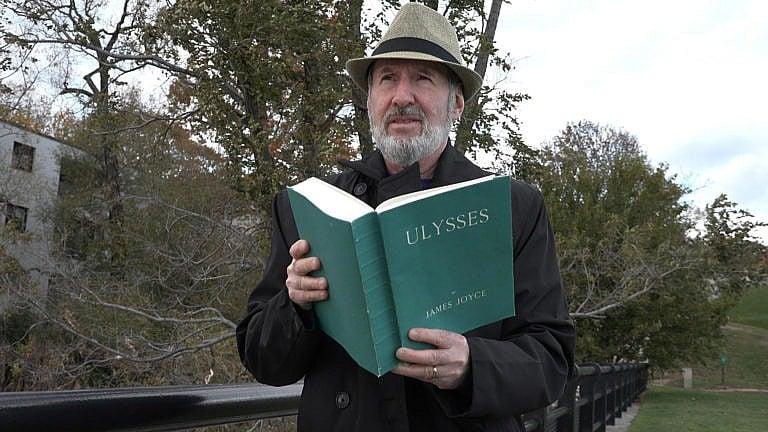

Michael Groden in the short film about him and his book “The Necessary Fiction: Life With James Joyce’s Ulysses” (Courtesy of Godfrey Jordan)

Share

Jillian Horton is a physician and writer and the author of the new memoir, “We Are All Perfectly Fine”

A beloved professor of mine died on March 25. His name was Michael Groden and he was a renowned Joyce scholar. He made me fall in love with The Dubliners, but that wasn’t even the half of the gift he gave me, and it all started with the dreaded first essay of the year.

It was 1993 and I was a student in my second year at Western University, struggling to write a paper about a poem by D. H Lawrence titled, “Piano”. I must have crumpled up a dozen lame opening paragraphs. At some point, in a fit of desperation, I made a wild change of gears. I folded a small facsimile of a notebook out of some old, cream-colored stationary and set to work with an artist’s pen. I tried to situate myself inside Lawrence’s writing process, imagining his drafts of the poem alongside sketches of his mother and his Latin conjugations. At some point, after I’d invested an entire weekend in this project, it became clear that there would be no time for me to write anything else, and I realized with a flicker of trepidation that I would be handing in this weird little chapbook to a professor I barely knew.

When it came time for me to slip my work under Professor Groden’s office door, I felt a mix of pride and terror. Pride for the lovely, detailed work of art in my hand, and terror because not only was it not an essay—it was the antithesis of an essay. I’d written a page-and-a-half note to accompany the project, trying to explain that I’d used the assignment as an opportunity to explore how the poem itself might have been influenced by the space in which it was created. But I’d never handed in anything like this, and I was acutely aware that as a scholarship student, failure meant a risk of losing the golden ticket that had enabled me to go to Western in the first place.

I felt sick as the days passed. I do remember the class when Professor Groden, as I still called him then, announced that he was done marking the essays and they hadn’t been a particularly good crop. My heart sank, and I shielded my eyes as he handed me back my little booklet. I snuck out into the hall to read his comments.

What a great idea to experiment like this. You’ve captured what could have been said in a traditional essay, but you’ve shown much more.

How can I remember his exact words 28 years later? I don’t have to remember them. I never threw out that notebook, or that piece of paper with his enthusiastic praise for the risk I’d taken. In fact, I had his note pinned up on a bulletin board for most of my undergraduate years, and it still lives in a metal box with some of my most precious belongings from that stage of my life.

Over the course of the next three years, Mike became one of my most influential teachers. I spent a fourth-year seminar writing essays and a short play under his direct tutelage. He treated everything I penned with tenderness, rigor and respect, pushing me to take as many creative risks as possible. He was wiry, kinetic, always on the move. I can still picture him darting into the Grand Theatre before the curtain rose on another play I had written. I remember soaking up his praise afterwards, how it kept me from ever wondering too much if my work was worthwhile, how he supported my decision to pursue a career in medicine. His voice was one of several that echoed in my ears and kept me writing, against the odds, for the next 25 years.

I hadn’t known when I took that first risk that Mike’s wife was the renowned American writer and poet Molly Peacock, or that he was already a person who saw traditional academic pursuits as necessarily creative. I also didn’t know how difficult his life had been. Diagnosed with melanoma more than a decade earlier, he had undergone one course of experimental treatment after another. He lived with a kind of uncertainty that is foreign to anyone who has never had to co-exist with the shadow of a life-threatening illness. Later, when I became a physician, I would come to understand the bullet he had dodged and would always be dodging, the psychological risk he took to continue to engage with life and plan for a future, because melanoma is often the ultimate gaslighter of cancers, receding just when you think all hope is lost, returning just when you think you’ve evaded it.

So it was for Mike. I gave a special virtual lecture at Western University earlier this month when I released my new memoir. I didn’t even know he was sick again. His wife, Molly, wrote me to say that even though his hearing was almost gone, Mike was watching me proudly, cheering me on as best he could.

Just a few months ago, I finally read Randy Pausch’s touching book, “The Last Lecture.” A celebrated professor himself, Pausch talks about the importance of not just paying it forward but paying it backward to our teachers, and the power of that loyalty.

We always imagine we’ll get a chance for one more coffee, to pay it backward at just the right time, to thoughtfully untangle what a teacher meant to us or how they helped to catalyze something important in our own lives. Then, suddenly, that opportunity is gone, and all we can do is pay our respect in this moment, settling our debts out in the open. How sorry I am that my lecture was his last. And how grateful I am that he got to hear it, the culmination of a lifetime of small creative gambles, ones he made it possible for me to take when I was first getting started, just when I needed him most