The rise of the internet’s ‘dirtbag left’

How a new strain of progressive leftism is using humour, irony, and diaper jokes to push back against the emerging alt-right

Chapo illustration. (Graeme Shorten Adams)

Share

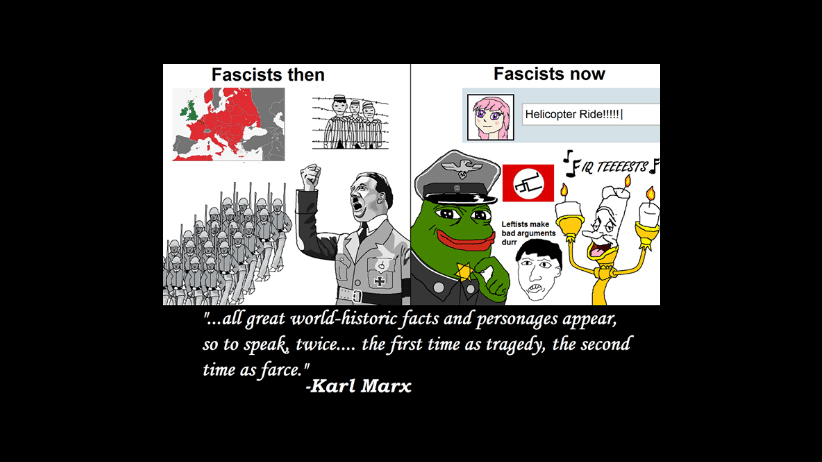

Earlier this year, a sloppily doodled MS Paint comic appeared on Reddit—the online news aggregator and so-called “front page of the internet”—juxtaposing images of 20th-century fascism with more modern symbols of far-right political thought. Under the column “fascism then” loomed the usual suspects: soldiers goose-stepping in formation, concentration-camp prisoners in striped pyjamas, a barking-mad Adolf Hitler. Under “fascism now” lurked a weirder assemblage of ideological signifiers of the so-called “alt-right”: a snickering cartoon frog in Nazi regalia, the crooning French candelabra from Disney’s Beauty and the Beast, an anime character, a badly drawn swastika.

The comic carried a caption courtesy of Karl Marx: “All great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice…the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.” The passage is often condensed to read something like: “history repeats itself: first as tragedy, then as farce.”

Making sense of the shifting terrain of contemporary far-right politics demands an understanding this move from tragedy to farce. On its face, the emerging alt-right—a term coined by American white supremacist Richard Spencer, a far-right thought leader who claimed that the alt-right had been “memed into existence” and is also known for being punched in the face on camera by an antifascist on Donald Trump’s inauguration day—seems like a joke. It’s a movement dominated by cruddy comics, memes, jokes at the expense of politically correct “social justice warriors” (SJWs), and the open trolling of good taste. It’s difficult to take the alt-right seriously—and, indeed, to understand whether it takes itself seriously.

But according to author Angela Nagle, whose new book Kill All Normies tracks the ascendency of the alt-right over the past decade or so, the movement is very real. Emerging online over the past decade, early iterations of the alt-right attracted what Nagle describes as “a strange vanguard of teenage gamers, pseudonymous swastika-posting anime lovers, ironic South Park conservatives, anti-feminist pranksters, nerdish harassers and meme-making trolls whose dark humour and love of transgression for its own sake made it hard to know what political views were genuinely held and what were merely, as they used to say, for the lulz” (“lulz” being a term for ironic jocularity). And the popularity of the alt-right has been further encouraged by the presidency of Donald Trump, whose open contempt for political correctness, brazen vulgarity, and occasional borrowing of alt-right memes on Twitter has made him a figurehead for this vanguard—a unifying force around which these assorted factions could rally, with varying degrees of irony and earnestness. Now these collectives of online trolls are nurturing real-world political agitators, from disgraced anti-political correctness provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos, to Oval Office insider—and noted admirer of Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl—Steve Bannon.

Still, in the rare instances where such groups are covered in the media, they tend to be met with a combination of incredulity (“they can’t actually believe this!”) and ambivalence (“oh, they’re just joking”). “It’s weird,” says Nagle, over the phone from downtown Dublin, where she makes her home. “There’s a mixed reaction: one is that they’re all fascists and the fascist takeover is just around the corner, and at the same time there’s the problem of not taking their ideas seriously, of not really being interested in thinking about their ideas. It’s kind of a contradictory, and lazy, response.”

As Kill All Normies makes abundantly clear, there’s a deeply disturbing agenda seething beneath the snowballing alt-right’s irony and in-jokes. “They always wrong-foot journalists by making them think that the alt-right is so complicated, that if you try to write about them, you’ll goof up and look stupid,” says Nagle. “But the stated goals of the alt-right include an ethno-state in America, and eventually a white empire in America, Russia and parts of Europe. That would necessitate war, at the very least, and probably genocide.”

And while it’d be easy to dismiss this fascist to-do list as a delusional racist fantasy shared by message-board trolls with dreams of goose-stepping across the Washington Mall, the alt-right—and its more watered-down version, which Nagle terms the “alt-light”—has a real presence in the United States. It’s embedded in Canada, too: A recent “free speech” rally in D.C. saw Richard Spencer speaking of the fear of white people becoming a minority in America, a panic shared by former Canadian ambassador Martin Collacott in a recent Vancouver Sun editorial. Canadian Gavin McInnes, who used to write crass jokes for VICE magazine before getting canned, has reinvented himself as a far-right commentator for Canada’s The Rebel and as the pater familias of a “pro-Western fraternal organization” called The Proud Boys, a Canadian detachment of which reportedly crashed an Indigenous protest held in Halifax on Canada Day, clad in the standard uniform of skinny jeans and Fred Perry polos. Alexandre Bissonnette, perpetrator of the January massacre at the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec City that claimed six lives, was revealed as being radicalized by alt-right ideology and online “trolling.”

Good liberals have been viscerally—and justifiably—repulsed by the ascent of such groups, and the way their ideology informs real violence. But what’s just as disturbing, says Nagle, is the ways in which the alt-right emerged online as a reaction to the left. Nagle’s book pulls double-duty as a deep, thoughtful critique of the left and of this reactionary online call-out culture. “There is no question,” Nagle writes, “that the embarrassing and toxic online politics represented by this version of the left, which has been so destructive and inhumane, has made the left a laughingstock for a whole new generation.”

Nagle sees the rise of the violent, hateful, and often deliberately confounding culture of the alt-right tied up inextricably with failures of the left. Where the internet was once viewed as a utopian space for free expression, and experimentation with thought and identity, it eventually became colonized by a calcified leftist sameness, thanks to sites like Tumblr and Twitter, where buzzwords and ideologies multiply and spread like viruses. There was also a certain sanctimonious and self-righteous tone that came to dominate these conversations. Certain strains of leftism—and especially those that valued identity above all other social and political categories—began to monopolize the free market of ideas, making the experience of being online if not entirely oppressive in its patrolling of ideas and verbiage, then certainly much less fun.

Many who were alienated by this culture drove deeper underground, to sites like 4chan and Reddit, where new mutations of far-right, anti-feminist, racist, Islamophobic, white supremacist ideologies—with their focus on memes, jokes, trolling and pushing back against political correctness—restored, for them, the earlier anarchic promise of the Internet. As Nagle writes, the emerging alt-right “had little in the way of a coherent commitment to conservative thought or politics, but shared an anti-PC impulse and a common aesthetic sensibility.”

The culture of call-outs and one-upping “wokeness”—a condescending term used to describe an overstated performance of political correctness—was diagnosed as far back as 2013 by British blogger and political theorist Mark Fisher. In his essay “Exiting the Vampire’s Castle,” Fisher decried the “stench of bad conscience and witch-hunting moralism” that emanated from the online social-justice set. He also identified the collective paralysis among those on the left who disagreed with those tactics, a “fear that they will be the next one to be outed, exposed, condemned.” Fisher, predictably, became a target of such condemnation after his essay was published; many ghouls returned to mock him when he committed suicide earlier this year.

“Anyone on the left with any independence of mind has experienced this backlash,” says Nagle. “People will look back at this period as a moment of madness—if it ends. I feel like there’s much more of an exciting, funnier left-wing culture emerging around people who are critics of it. That’s not a coincidence. You can’t be a puritanical purger and have a sense of humour.”

Enter a new culture of the online left. It’s a reinvigorated wing that’s simultaneously anti-alt-right, anti-PC and anti-SJW, anti-centrist and against liberal-democratic line-toeing. It’s a movement that uses many of the tactics of the online alt-right—humour, memes, Twitter trolling and open animosity—while remaining committed to progressive leftist ideology. It’s sometimes called the “alt-left” or the “vulgar left,” or the “Dirtbag Left”—a term coined by Brooklyn based writer, podcaster, and activist Amber A’Lee Frost.

Frost is a co-host of the popular politics podcast Chapo Trap House. Founded by politically savvy Twitter jokers Will Menaker, Felix Biederman and Matt Christman, Chapo Trap House gained massive traction during the 2016 U.S. presidential primaries among online factions of “Weird Twitter” and “Left Twitter” who were eager to push back against the ascendency of war-hawk Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton and stem the tides of #ImWithHer memes. “Twitter was poised to examine the primaries in a way that the established media either would not or could not,” Frost writes in an e-mail. “This was a great moment in terms of consciousness-raising and communication.”

A given Chapo episode sees the hosts yukking it up at the expense of hacky mainstream media op-eds (New York Times columnist Ross Douthat is a favourite target of the gang’s derision), or critiquing the limp, liberal identity politics of the recent, and much-lauded, Wonder Woman movie. With its bricolage of trenchant political commentary, obscene inside jokes, absurdist comedy, socialist boosterism, and giddy vulgarity, Chapo became a kind of citizen’s band radio frequency for leftists isolated by the pervading online culture that practices sanctimony over solidarity. It currently receives more than US $66,000 a month in listener donations, nearly triple that of other top-earning podcasts fan-funded through Patreon. “I think people are just relieved to know they can be socialists without being humourless, sanctimonious or pious,” says Frost. “We let people have fun in an atmosphere where it’s hard to laugh.

Where more orthodox forms of leftism are marked by defeatism and self-seriousness, Chapo is shot through with irony and self-deprecation. It emboldens the left not only to criticize itself, but to laugh at itself. See, for example, the very embrace of the term “Dirtbag Left.” “[It] speaks to a lot of people who have been dismissed or chided by liberals for embracing vulgarity, eschewing sanctimony or piety, and refusing to be civil to the right wing,” says Frost. “The libs have no principles beyond good manners, so I think ‘Dirtbag Left’ says something positive about what we do believe, and what we’re willing to ruthlessly fight for, regardless of established etiquette.”

This disregard for standards of civility or “good manners” feels especially important to the emerging Dirtbag Left. When Michelle Obama beamed during last year’s presidential primaries that “when they go low, we go high,” the mainstream media and the liberal establishment praised her for her dignity and restraint. But for many others, Obama appeared not as a torchbearer of good governance and civic rectitude, but a fool. Like so many institutional liberals, she fundamentally misunderstood the degree of animosity the Democrats faced, comforted in the false belief that their ideals or courtesy and good manners would somehow win the day.

What Michelle Obama—or Canadian writer Jonathan Kay, who recently issued a critique of social media boorishness in a National Post essay—miss in their clarion calls for civility is that, for many, politics isn’t just some academic discussion or reimagining of a collegiate debate club: It’s a battle. It’s about drastically opposed visions of society rubbing against each in open conflict. The reinvigorated left doesn’t want to debate; it wants to disgrace.

The fact is that there are many on the left who don’t want to be civil—who want to mock and joke and hurl ad hominem and be as baseless and vulgar as possible. And why? Well, for one thing, it’s productive (and fun!) to unnerve those in power, and to make them feel uncomfortable in their laziness and privilege. And if it’s acceptable for members of the utterly powerless online liberal #Resistance to tweet at Donald Trump calling him a “Cheeto” or a “carrot” as if he’ll miraculously resign when he’s read it for the 17-millionth time, why is it not also valid to needle more immediate villains with harsher, more pointed criticisms?

These tactics will likely present a problem for some. The valuing of vulgarity and snarky hostility (“so much for the tolerant left!”) may scan as cannibalization and in-fighting among those with loosely shared agendas (i.e. anti-Trumpism). The dirtbag left understands this. What they reject are progressive-leftists being neglected, despite the foundering of the liberal/Democratic institution. They’re tired of sitting, slouched and bored, elbows on the table, at the kids’ table. And unlike the purely anarchic alt-righters doing it “for the lulz,” the alt-left offers a coherent, practical, progressive political agenda. As Chapo co-founder Will Menaker put it on a recent episode of the show, addressing an imagined audience pragmatist liberals and centrists: “Yes, let’s come together. But get this through your f–king head: you must bend the knee to us. Not the other way around. You have been proven as failures, and your entire worldview has been discredited.”

Now, just as the Reddit-incubated alt-right is finding horrifying expression in real-world political violence, the sundry gripes and demands of disaffected modern progressives appear to be receiving good, honest answers. The arrival of populist socialist politicians like Bernie Sanders in the U.S. and Jeremy Corbyn in the U.K. speak to the empowerment of a reinvigorated left. It’s not just about scatological jokes and mean tweets; it’s about mobilizing people in a way they want to be mobilized, to seek real, practical alternatives to the entrenched consensus, like subsidized education, healthcare, affordable housing, higher corporate tax rates, government oversight to prevent whole apartment blocks immolating, and ending bloody, colonial adventurism in the Middle East.

As Chapo’s Frost sees it, the end goal of Left Twitter and catalyzing podcasts like hers is to help the left regain its footing, to organize—and ultimately unplug. “The most important thing social media can do politically has always been to get people off the internet,” she says. “People need to get offline and plug into organizing and campaigns in the real world.”

Like the alt-right, this new left recognizes that humour, and that anarchic sense of intoxicating liberty provided by the internet, can draw people into the fold. If, as poster boy white supremacist Richard Spencer believes, a political ideology can essentially be “memed into existence,” then it can also be memed out. If the alt-right can push for a white, patriarchal, pro-Christian empire in the guise of a smirking cartoon frog, then online-savvy socialists can issue a call for robust trade unionism and shoring up social welfare state inside jokes about the sitting President of the United States’ overstuffed adult diaper exploding. If world-historic tragedy can rear its head as rotten farce, then maybe revolution—or at least reasoned, thoughtful, progressive change—can, too.