An interview with the woman who found Richard III

Philippa Langley did the impossible. She discovered the last English king slain in battle.

Richard III king of England, painting by an anonymous artist, no date. (Getty Images)

Share

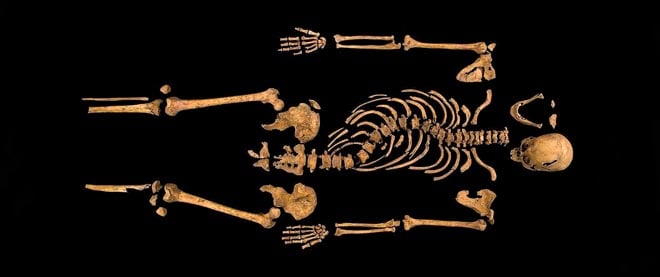

On Feb. 4, 2013, experts in Leicester, England, confirmed the bones of King Richard III had been identified, more than five centuries after he’d been killed on Bosworth Field by the invading forces of Henry Tudor in 1485. The discovery is due to the efforts of one woman: Philippa Langley. In The King’s Grave: The Search for Richard III, to be published in Canada on June 3, Langley and historian Michael Jones interweave her battle to uncover his bones with an evaluation of Richard’s tortuous life and death, including how Tudor propagandists such as Shakespeare created a murderous monster of a man.

No one was sure where he was buried. Rumours had his body consigned to the River Soar, while others reported he was buried in the choir of the long-vanished Church of Grey Friars. Interested in writing a screenplay on the monarch, Langley travelled to Leicester in 2004 to see possible locations where Grey Friars may have stood, including a parking lot belonging to the social services department. Knowing she’d never get permission for a hunt for long-lost royal bones, she tied it to something archaeologists and Leicester wanted to locate: Grey Friars. Taking advantage of new research into Bosworth and the church, she tenaciously raised funds and got officials and scientists to sign onto a two-week excavation of three trenches in that car park. It was the longest of shots that parts of the friary and church could be found, and one of those trenches would hit the choir. On Aug. 25, 2012, the first day of the dig, they found Richard.

Philippa Langley talked with Maclean’s a week before the High Court ruled that Leicester had the right to bury Richard in its cathedral.

Q: How did you become a Ricardian [a person who wants to rehabilitate the reputation of Richard III]?

A: I read a book in 1998 by Paul Murray Kendall. I hadn’t been taught about the Wars of the Roses and Richard III in school, so what I had in my mind about this king is the Shakespearean version. This biography knocked me sideways, because Kendall uses historical sources, records and the accounts to talk about a man who was loyal, brave, pious and just.

As a screenwriter, that absolutely fascinated me: I wanted to know how one man could be two different characters. I needed to research it for myself, so I joined the Richard III Society, because they have the best archives, the best brains and the best knowledge of Richard III.

Q: And what was your conclusion about who Richard III was?

A: He was a man of his times, a medieval man, for sure. But he wasn’t as the Tudor writers and Shakespeare painted him. The man I could see in the historical sources was a man who seemed very concerned with justice and loyalty and doing the right thing most of the time.

Q: Was he ruthless?

A: They all had to be ruthless, the men and the women. They were ruthless times. He was not as ruthless as those around him, and that’s definitely the key point. Richard was made, at the age of 18 or 19, constable of England. The constable had the power to execute at will. But Richard, you can see, he stayed his hand. He would have to see that someone was definitely guilty of something before he would authorize a punishment. If you put that in relation to some of the others who were constables of England, Richard is way far and beyond them in his temperance in that role.

Q: Do you think he’s ever going to be fully cleared of killing the princes in the Tower?

A: I think there’s a chance, because there’s so much interest now in Richard III that new research is being done. There are things that I’m doing, that I can’t tell you about, but we’re looking in places they haven’t looked before. I think there may be something in an archive somewhere, or some documentation, or in a household book of a great family. We don’t know, but I think it’s time to start looking, because I think this mystery can be solved.

Q: When did you get the idea of searching for Richard’s body?

A: I took a trip to Leicester and some Ricardian friends told me to go to this car park, because they thought it might be part of the larger Grey Friars precinct. Somewhere in that large precinct may have existed the Grey Friars church where Richard was buried.

I had this experience as though I was walking on Richard’s grave, and it became the catalyst and the driver for a complete 180-degree U-turn in my research focus. I went from researching his life to researching his death and burial.

Q: Describe what the area looked like before the dig.

A: It was an open-air parking area surrounded by Georgian and Victorian buildings. About 70 to 80 cars can park there. I went to this particular area that I was drawn to and, just to my left, I saw a hand-painted letter R on the tarmac, which was a reserved parking space. That was the first parking bay, and they found the body in the second parking bay, exactly where I had my experience.

Q: How close did the archaeological excavation come to not being started?

A: It was on a knife’s edge for 3½ years. We were in the worst recession in living memory. No one, but no one was interesting in digging up a car park, even if we were going in search of a king. The academics don’t go to search for famous people; they were happy to look for the church, but I had to pay for it because I was using archaeological contractors. They couldn’t do it without the money being there.

The car park I wanted to dig was a very busy, important car park for Leicester city council, so getting their permission to dig that car park was huge. And I have to say it’s thanks to them that this search happened. They gave me permission to dig.

It was a two-week dig with one week re-installation work afterward, so a three-week project.

Q: When did they find Richard?

A: We found the body on the first day within four hours, and in the exact place I said he would be. But we didn’t know it was Richard then; we’d only started digging.

The archaeologists had to continue to dig the site, because we didn’t even know if we were in the Grey Friars precinct site. A week later, we discovered what looked to be the church, and then the archaeologists wanted to dig in another trench because it was farther east, and we know Richard was buried in the choir, which is in the east. So that decision made sound sense. But I’d spent 7½ years, by this point, getting to the car park; I wanted the remains found farther to the west exhumed, because that was part of my journey. We exhumed them on Days 11 and 12 of the dig and it turned out to be him.

Q: What was your reaction when you saw the remains being revealed?

A: That was a tough one, strangely. Because I’d spent so many years researching Richard III, I knew he was very physically able, and physically active. We know he fought in three battles, and we knew his itinerary. This man was never off a horse; it looked like he had a very strong work ethic. So when they revealed the remains in the grave and when the specialist said he was a hunchback, that absolutely threw me.

I thought, “This can’t be Richard III, because it doesn’t add up”—also because we have descriptions from people who met him during his lifetime, and nobody mentions it. So I thought, “This can’t be him.” But then when they showed me the battle trauma, it was very clear this was Richard.

But when the specialists got him back to the university and had a look at the remains, they realized he wasn’t hunchbacked. (That’s such an inappropriate word, but we don’t have another.) He didn’t have kyphosis, he had a scoliosis. The grave had been cut too short for the body, so that’s why his head was up and forward and on his chest, which is what happens with kyphosis.

When they said he had scoliosis, it made sense, it fitted, because it doesn’t stop you from having a very active life. Usain Bolt has scoliosis.

Q: The discovery and identification made headlines around the world. Do you think attitudes before the announcement are the same as the attitudes after it? Has there been a shift?

A: Yes, there’s been a big shift. When we were examining the remains on the table, the specialist called him a hunchback. I asked if scoliosis patients are called hunchbacks, and he said no. So I couldn’t understand why he was calling this guy a hunchback. And I think there’s a big perception of Richard III; that’s what’s always been said about him. Now it’s been a major step forward to getting to the real man, rather than the caricature. We’ve been able to blow so many myths that surround Richard, just by finding his remains.

Q: Now there’s a legal dispute about where and how his bones should be buried. Can you explain it?

A: A group of collateral descendants of Richard III have made a formal application to the courts to enable consultation to take place on where Richard is buried and the manner in which he is buried. There is a judicial review that took place on March 13 and 14 in London on whether consultation takes place or not.

Q: The initial judge who allowed the dispute to move forward made a point that this isn’t an ordinary exhumation, but that of a monarch. What is the general attitude within the country to the need for consultation or not?

A: I’ve been going up and down the country doing talks about the discovery. What’s coming back to me is the need for consultation. People up and down the country say we can’t bury an anointed king of England and a former head of state without some form of consultation. Whether the judges say that is another thing.

Q: What is your view?

A: When I was doing the project, I went to the Ministry of Justice that is responsible for issuing exhumation licences. They were clear that some form of consultation would have to take place if Richard were found. The landowners, Leicester city council, who gave me permission to dig, were clear that consultation would have to take place. Even the contractors on the dig, the archaeologists, also said at one point that some form of consultation would have to take place. I always thought some form of consultation would take place.

Q: Did you expect the post-identification legal questions to be raised?

A: No. My lead partner, Leicester city council, was always going to consult on the matter, and they would hold the exhumation licence. If everything had gone as we expected, Richard would be reburied by now, and consultation would have taken place.

But I’m afraid, because of a mistake, the exhumation licence went to the University of Leicester. They took the unilateral decision not to consult, and it’s that decision that has put us in this position.

Q: How was that mistake made?

A: We have a real issue with exhumation-licence application forms. They don’t have enough space on them to detail all the information you need to detail, such as who the client is, what happens to the remains after exhumation, who has the permission to exhume them and who’s going to look after them. So what happened on the application form was that the archaeological contractors who are based at the university, but are an independent business at the university, couldn’t get their name on one line. Their name is University of Leicester Archaeological Services, so they had to put “Archaeological Services” on the next line.

A comma was inserted by the Ministry of Justice after “University of Leicester” so it looked like it was the University of Leicester who were applying for the exhumation licence. They weren’t. It was Leicester city council.

Q: That’s how the entire legal issue began?

A: Yes. It’s a big mess and nobody is talking about it. We can see where the mistake has happened and we can see that Leicester city council would consult. All this has been caused by a comma. There would have been no Plantagenet Alliance [the group of collateral descendants fighting in the courts for consultation], no judicial review, none of it, if it had happened the way the Looking for Richard project had outlined. The comma caused the whole mess.

Q: What is your preferred outcome? Where would you prefer to have him buried?

A: I don’t have an issue with where Richard is buried.

My issue is how he’s buried. I made it very clear that the ethos in the Looking for Richard project was that he wouldn’t be treated as a scientific specimen or resource or relic or object. I wanted him treated as a human being, a fallen warrior on the battlefield and, in that sense, I wanted him to receive what we give all who have fallen on the battlefield: They are laid out anatomically within their coffins and they are sent to a place of sanctity and rest prior to reburial.

That was very clear in my agreements. Once Richard III was identified, I would be able to take him to a place of sanctity and rest, so he wouldn’t stay in a box in the university. I’m still waiting to get that agreement from the University of Leicester.

So right now, Richard is still in a box, in the university, and he’s not in a place of sanctity and rest. I think that’s inherently wrong.