What a blood plasma-for-profit clinic means for public health care

The federal government has quietly approved a plasma-for-profit clinic in Saskatoon, drawing fiery criticism from politicians, scientists and patients

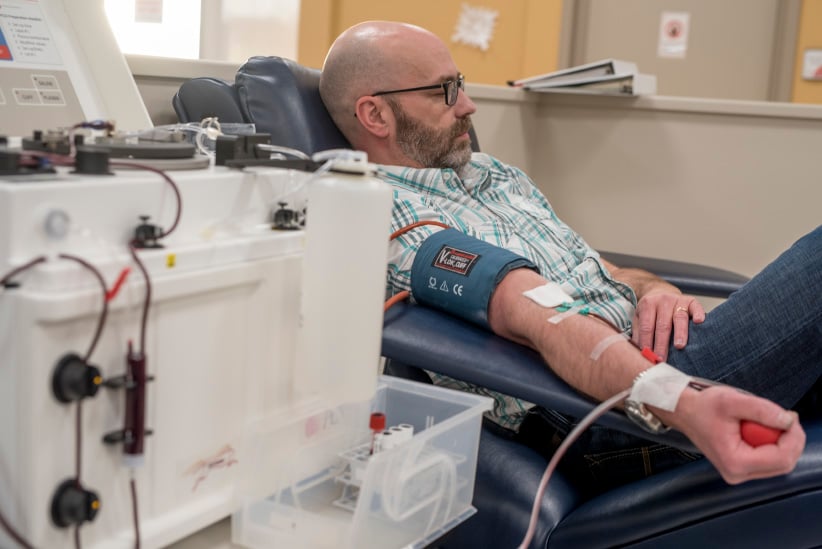

Separation of red blood cells and plasma. After separation the red blood cells are re-injected to the donor.(Photograph by Derek Mortensen)

Share

Three days before Christmas 2016, jingly seasonal music fills the air at Canadian Plasma Resources (CPR) in Saskatoon, located in a non-descript building in a quiet industrial stretch. In one direction, a strip of pawn shops; in the other, the Saskatchewan Polytechnic. Prospective donors are greeted by an artificial Christmas tree, a Purell dispenser and screening restrictions: medications they can’t be taking, that they must be between 17 and 61 years of age and weigh at least 50 kg. They’ll need SIN documentation, proof of a current fixed address, and government-issued photo ID. A young man is filling out a 42-question donor form, with queries from “At any time since 1977, have you received money or drugs for sex?” to “Are you aware of a diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease among any of your blood relatives (parent, child, sibling)?” Another 21 questions will be reviewed during a nurse’s examination.

Inside, the plasmapheresis room betrays no hint of holiday bustle: only four of 34 reclining chairs are occupied—three women and a man, all middle-aged. A TV plays overhead as straw-coloured plasma courses through tubes. A staff member ferries plastic containers filled with the golden liquid—the protein- and antibody-rich component remaining after white and red blood cells, platelets and other cellular components are removed—to the back for processing and freezing. For their time, typically an hour and a half, donors receive a $25 Visa gift certificate—or they can donate that amount to a charity for a tax receipt. Unlike full blood, which can be donated every two months (three for women), plasma can be given weekly. Frequent CPR donors are eligible for bonuses; “Super Hero Rewards” members qualify for monthly draws with quarterly draws for “silver” and “gold” donors with “prizes valued at over $2,000.” CPR’s recruitment techniques include social media and ads in university bathrooms. The location now has 800 registered donors, only 30 per cent of their 2,500-donor target, says CEO Barzin Bahardoust.

Canadian Plasma Resources is not Canada’s first paid plasma operator: the former Cangene in Winnipeg has paid for plasma with a rare antibody since the 1970s, and more recently has been collecting regular plasma. But the cascade of events surrounding CPR’s ill-fated entry into the Ontario market in 2013 put it in the crosshairs. CPR’s proposed locations, next to a Toronto men’s shelter and Hamilton methadone clinic, led to a public outcry and 2014 provincial legislation banning payment for blood products passed unanimously; Quebec has had a similar law since 1994. Police raids of CPR’s Toronto location and its threat to sue the provincial government,made headlines. Health Canada’s licensing of CPR’s Saskatchewan location in February 2016—and its proposed entry into New Brunswick this year and British Columbia thereafter, with stated plans to have 10 centres operational by 2020—has divided not only provinces, but patient groups and politicians as it exposes the backroom politics and economics that course through the once-public Canadian blood system.

The very mention of selling blood product resonates in a country scarred by the “tainted blood scandal” of the ’70s and ’80s. Bureaucratic negligence, regulatory malfeasance and corporate greed contributed to Canada’s greatest health care tragedy, one that saw more than 8,000 Canadians die—and more than 30,000 afflicted—from blood infected with HIV and hepatitis C. The details are horrific. Montreal brokers, who imported blood from Arkansas prisoners, relabelled it “Canadian blood” and then exported it, leading to hepatitis C outbreaks in Canada and internationally.

The resulting inquiry, a five-year investigation, produced a 1,200-plus page report in 1997. Justice Horace Krever referred to a “nationwide public health calamity.” Blame didn’t lie only with the Canadian Red Cross reacting too slowly to the AIDS crisis, Krever concluded; it was systemic failure driven in part by the profit motive. His report recommended people “should not be paid for their donations, except in rare circumstances.”

The Krever report shaped the current volunteer-based public blood system: Health Canada is the regulator, responsible for blood safety. Canadian Blood Services (CBS) and Héma-Québec were founded in 1989 to manage the country’s supply of blood and blood products. What Krever could not have anticipated, however, was the explosive rise of a market for plasma. Fresh plasma, collected from voluntary donors in Canada, is used for transfusions. Of this there is no shortage, with demand declining as keyhole operations require less and less blood. Demand is soaring, however, for “source plasma,” a raw ingredient pooled before fractionation, a processing technique that separates it into component parts for treatments: albumin for burns and trauma, factor VIII to help clotting in people with hemophilia and other bleeding disorders, and intravenous immunoglobulin (Ivig) for infections and immune disorders. The Ivig market is growing at an estimated eight to 10 percent a year, with Canada one of the highest per capita users. Ivig product can run $7,000 per treatment—and more than $200,000 annually. Plasma is the stuff of pharmaceutical alchemy: A donation that nets a donor $25 can yield pharmaceutical products worth at least $300, hence the proliferation of paid-plasma centres in the U.S., Germany, Hungary and the Czech Republic.

Patient groups dependent on plasma-derived drugs, including the Canadian Hemophilia Society (CHS), vocally defend the need for paid plasma. CBS and Héma-Québec already import plasma-protein products from the U.S., manufactured with plasma collected from paid U.S. donors, they note. Yet the matter is controversial, even within patient groups. Minutes from an April 2013 CHS meeting indicate the Ontario and B.C. chapters voted against paid plasma in Canada. The B.C. chapter subsequently lost funding from head office.

Safe blood advocates speak in terms of the integrity of the system: “Pay for plasma means a private corporation is owning some of the sovereignty over our public blood system and our donors and it is in direct opposition to Justice Krever’s landmark inquiry,” says Kat Lanteigne, co-founder of advocacy group BloodWatch.

There’s also concern that plasma collected by CPR will not ever directly benefit Canadian patients. CPR boasts a “Give plasma, give life” motto and offers assurance on its website that “by becoming a plasma donor, you can help Canada satisfy its own needs for plasma therapies.” But there is no guarantee, or legal requirement, that the plasma it collects ends up in Canadian hospitals or clinics. Currently CPR’s plasma is in limbo, sitting in a freezer while the company awaits the necessary licences to ship for fractionation or to bring the components back to Canada and sell them.

The irony of a for-profit plasma facility opening in Saskatchewan, the cradle of Canadian medicare, is not unnoticed. Sheri Benson, NDP MP for Saskatoon West, where the CPR facility is situated, heard about it when it opened in February. She wasn’t surprised the Saskatchewan Party-led provincial government gave a green light, given its openness to health care privatization. What alarmed her, she said, was the newly appointed Trudeau government—specifically Health Minister Jane Philpott, a medical doctor—approving it: “I was disappointed that the decision was made by this minister of health, with her public health background and some of the rhetoric we’ve heard from the Liberal government about the importance of science and evidence.”

Michael Decter, a former Ontario deputy health minister and adviser to the Krever commission, also expresses dismay over the licensing. “I was enormously disappointed and upset,” he says. “The minute you enter a for-pay plasma element you begin to undermine the voluntary collection.”

That risk was made manifest on Dec. 21, when CBS CEO Graham Sher announced CPR’s Saskatoon operation was causing the decline in volunteer donations in the city. Two months earlier, in October, at Canadian Blood Services’ annual general meeting, Sher asked governments for “a pause of support for commercial activity” in plasma until CBS unveiled its own plan to increase plasma collection, expected this month. Canada currently only collects 17 per cent of the plasma it requires for plasma-derived treatments; the CBS wants that number to rise to 50 per cent.

The arrival of paid-plasma, the first human material Canadians can sell (selling sperm, eggs and embryos is prohibited) on the 20th anniversary of the Krever inquiry, tests the country’s commitment to public health care, says Matthew Herder, an associate professor of medicine and law at Dalhousie University: “Certainly it raises pretty dark questions about the tainted blood scandal and how seriously we continue to pay attention to what went wrong.”

Canadian Plasma Resources was a company born of confidence in governments’ appetite for a for-profit plasma industry. Its parent company, ExaPharma, is owned and operated by the Riahi family which has experience in the global pharmaceutical industry, and was incorporated in July 2009, a month after its principals met with Health Canada. CPR was registered in November 2010 to “operate plasmapheresis centres.” In November 2012, it applied for federal licences with plans to open three centres in Ontario. Run by Barzin Bahardoust—who affixes “Dr.” before his name in reference to his Ph.D. in electrical engineering—it invested some $9 million in real estate and equipment, and hired staff, among them former CBS employees and veterans of the German plasma-fractionation industry. All was proceeding smoothly until early 2013 when media revealed the proximity of two centres to drug users and an indigent population, imagery that raised concerns over blood safety and paid-plasma companies exploiting low-income, vulnerable communities.

In response, in April 2013, Health Canada convened a closed-door, one-day meeting of “stakeholders”: patient groups, government, and the Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association (PPTA), the industry group representing the $20-billion biopharmaceutical plasma-dervived therapies sector. No media was allowed. Activist Michael McCarthy, a hemophiliac who contracted hepatitis C in 1984 from tainted blood, was present. The meeting was a “sham,” he says. “It wasn’t an open and transparent process.” McCarthy, a senior adviser to former Ontario health minister Tony Clement, knows government manoeuvring: “It looked like an orchestrated meeting where the outcome was preordained,” he said. “You had CBS, the PPTA and Health Canada talking about, ‘All we have to fear is fear itself. Science will protect us this time around.’ ” What scared him, he said, was going down the same road that caused us to get into trouble in the ’70s and ’80s, with “Trust us, the science is good this time,” says McCarthy, also lead plaintiff for Canadians Affected by Tainted Blood. “And that’s not what the story was about. It was about making the same mistakes. This is the riskiest part of the blood system; this is where the money is made; this clouds people’s judgment.”

The Health Canada consultation process also summoned a charge of “policy laundering”—the term for governments manufacturing a record of support for a pre-determined policy objective—from health care policy scholars at Dalhousie. Writing in Impact Ethics, Matthew Herder and Françoise Baylis, a professor who specializes in bioethics, argued that claims made by Health Canada and CBS—among them “collecting enough domestic plasma to be self-sufficient in plasma products is not operationally or economically feasible with a volunteer model”—will eventually “become ‘the’ supporting evidence for subsequent claims in support of a pay-for-plasma policy.”

Related: Should we pay for blood?

A voluntary program aimed at domestic self-sufficiency hadn’t been attempted, they wrote, noting Health Canada “cannot legitimately extrapolate from the experience of other countries that are culturally very different from Canada, do not have a similar health care system, or commitment to altruistic blood donation.” They questioned the lack of evidence to show a commercial plasma collection system would, in fact, ensure a sufficient supply of plasma products in Canada and asked Health Canada to “seriously explore alternative strategies to encourage and facilitate voluntary plasma donation.”

Anyone following blood politics will recall that by 2013, CBS was getting out of plasma collection, closing a centre in Thunder Bay in 2012, citing declining demand for transfusion plasma and inefficient collection costs. Sher appeared unworried about the negative effect paid-plasma centres might have on voluntary donations in a 2013 interview with Maclean’s, despite available data that suggested that indeed happened. CBS was then busy exploring the prospect of becoming the central depository for organs and tissue transplant in Canada, an initiative that failed to gel.

Paid plasma was a campaign issue in the 2014 Ontario provincial election; Exapharma/CPR created the Ontario Plasma Coalition, spending $209,060 to promote private plasma collection. Bahardoust’s testimony in December 2014 to Ontario’s standing committee on social policy looking at paid plasma promised “a $400-million investment in Ontario to open 10 plasma collection centres and to build and operate a fractionation plant with strategic partner Biotest AG.” He spoke of 2,000 new manufacturing jobs for skilled workers being lost to the province: “Now the investment and jobs will go to those provinces where we have agreements to operate, beginning in Western Canada.” That month, Ontario banned payment for blood and Health Canada licensed two CPR facilities in Ontario that would never open.

By then, CPR had brought in lobbyist Jim Pimblett, a former adviser to former prime minster Paul Martin and Liberal leader Michael Ignatieff, who travelled the country to ignite interest in the economic benefits of paid plasma. Alberta and Nova Scotia proved resistant, while Saskatchewan, Manitoba, New Brunswick and B.C. were receptive. CPR’s meetings with premiers and health ministers included two board members from Biotest AG. According to a Freedom of Information request, CPR met with B.C. Health Minister Terry Lake in November 2014 to discuss CPR’s proposal “to establish a plasma-based pharmaceutical business in B.C. employing more than a thousand people.” An email from Pimblett to the government refers to Biotest, a German-based multinational, as a CPR “investor.” Biotest runs 13 plasma collection centres in Europe and 22 in the U.S. and has major fractionation capacity. It also has deep pockets, with reported 2015 revenues of $825.6 million. In an email to Maclean’s, Pimblett says he “erred” in calling Biotest an investor: “Biotest is not a shareholder or investor in [CPR] and they never have been.” He adds “there were discussions about Biotest having an option to invest but Biotest ultimately chose not to pursue it . . . I must have incorrectly characterized the discussions between the companies as complete when they were not.” CPR and Biotest AG have “a strategic partnership, Pimblett writes, in which CPR “supplies Biotest with plasma for fractionation, and Biotest in turn provides [CPR] with finished pharmaceutical products for the Canadian market while they build fractionation capacity in Canada.”

Other emails obtained under Freedom of Information by the Saint John Telegraph Journal indicate Pimblett also met with Victor Boudreau, New Brunswick’s health minister, in April 2015 to establish “shared messaging” over possible public backlash regarding a proposed Moncton clinic close to the university. On Sept. 16, 2015, the minister sent a thank-you note to Bahardoust for meeting with business development agency Opportunities New Brunswick. He reassured him that “the government has not introduced, nor does it plan to introduce any new legislative or regulatory measures that would prohibit, or act as a barrier to this type of operation.” Boudreau declined Maclean’s request for interview.

B.C. Health Minister Terry Lake was so inspired by the meeting that he wrote an op-ed in the Vancouver Sun in April 2016, titled “Pay-for-plasma poses no threat.” He focused on potential jobs and said: “I’ve been assured by Canadian Blood Services that the technology and systems now in place— whether for products derived from public or private plasma donations—safeguard the supplies of these products.” Sher echoes the reassurance to Maclean’s. “Much of the controversy around the plasma file are premised on issues of historic concern around safety and stuff that occurred in the 1980s,” he says. “Those are not the issues today. We are not concerned about safety of plasma derivatives from paid versus unpaid donors.” David Page, executive director of the Canadian Hemophilia Society, expresses frustration when the issue of safety comes up. “This is not a safety issue and anyone who says it is doesn’t know what they are talking about,” he says. “Patients do not need to be told that products—and most products in Canada come from U.S. paid donors—are not safe.” As support for this view, patient groups and industry refer to the “Dublin Consensus,” a three-page paper established in a 2010 meeting in Dublin attended by patient groups and industry. Blood-safety advocates denounce it as an industry paper, arguing the gathering was organized by a plasma users coalition created by the PPTA. Sher defends it: “It is a patient and stakeholder form, not an industry form. Without access to the commercial for-profit industry internationally, there wouldn’t be sufficient plasma drugs to meet patient needs. That’s what Dublin says.”

Hemophiliac Curtis Brandell, who lives in Vancouver, disagrees. “By paying people for plasma over a long term you’re exposing people to risk because there are definitely pathogens that may come along that could possibly evade our new-found technology,” he says, adding: “If it is so good, why even test the blood?” Ivig drug labels themselves offer caution: “Product is made from human blood and may carry a risk of transmitting infectious agents,” says one.

Decter recommends caution. “Blood is inherently dirty,” he says. “We didn’t know what HIV was when it turned up. We didn’t know what hep-C was when it turned up. I’m a skeptic when people tell me that it’s all safe now. That’s not the precautionary principle and that’s not the history of blood where we keep finding new things that cause harm. I don’t mind being a Luddite on this one. Better safe than sorry.”

Health Canada’s authorization for the Saskatoon facility began on Dec. 18, 2015. The site was was inspected on Jan. 18, and a licence was granted on Feb. 2, 2016; it opened two weeks later with Health Minister Dustin Duncan in attendance. Pimblett coordinated supportive messaging with patient groups. Emails between him and the Canadian Organization for Rare Disorders (CORD), obtained by Maclean’s, reveal the organization asking Pimblett to “submit on our behalf.” In the press release, CORD said it “appreciates the dedicated efforts of Canadian Plasma Resources to achieving this first plasma-collection facility.” Paid plasma is vital, says CORD president and CEO Durhane Wong-Rieger, who acknowledges CPR’s plasma may not benefit Canadians. “But it will add to world supply,” she says. In that world supply, Canadian plasma has high value, says Bahardoust, due to perceptions of the nation’s health. It’s common for blood patient groups to work with industry, Wong-Rieger says: “We all work with manufacturers.” Page says the CHS receives “substantial funding” from industry but remains independent in its governance.

CBS’s position on paid plasma has been erratic. In February 2016, CBS issued a statement expressing confidence in a dual voluntary-paid system while noting it would “continue to monitor these practices closely.” Then, in October, Sher called for governments to “pause” on commercialization. Two months later, CBS announced declining donations based on “anecdotal evidence that there’s brand confusion,” says a spokesperson, referring to staff receiving comments such as, “I donated plasma with Canadian Blood Services just down the road.” Bahardoust denies donor overlap: “There are only a handful of [CBS] regular blood donors who have joined our program out of the 800 plasma donors we have.”

Health Minister Jane Philpott has come under fire for the CPR licence in both the House of Commons and Senate, where she was grilled in November by Sen. Pamela Wallin, who asked why CPR’s licence was granted, given potential competition with CBS’s voluntary donors. Philpott waffled, referring to Canada as “having one of the safest blood supply systems in the world, in large part because there were serious errors made in the past and we had to correct our ways.” She then deflected responsibility to the provinces. Health Canada’s role is to ensure facilities are safe and regulated, she said: “The decision about a specific clinic, whether it can operate and whether it can compensate donors . . . with something like a $25 gift card for groceries, for example—those decisions are not made by Health Canada but by the provinces and territories.” She referred to the “Dublin Consensus” as evidence that “the blood supply in this country is safe and that plasma protein products used in this country are safe.”

Wallin responded that her concern was not safety, agreeing “standards are quite high,” but rather accountability: “Because several provinces indicated that they don’t support or like this activity, is there any reconsideration of this on your part in terms of licence-granting?” Philpott deflected again to the provinces, calling the matter one of “provincial jurisdiction.” Decter sees politics at play: “The federal government is trying to negotiate a health accord with provinces with disparate views on this issue; they’re not going to touch this issue. They should but they’re not.” The minister declined Maclean’s interview request.

In terms of CBS’s request for “pause,” Health Canada told Maclean’s via email it “will carefully assess the concerns raised by CBS, and will be consulting its provincial and territorial partners, in order to inform next steps.” In an interview, Liz Anne Gillham-Eisen, acting director for the office of policy and international collaboration, says the “pause” request was directed at the provinces, not the feds. When asked if anyone held ultimate responsibility for the Canadian blood supply, she answered it was run “jointly.” In a clarification, Health Canada writes that the blood system is collaborative: “In the case of an unforeseen or broader crisis that affected multiple parts of the system, the parties would use existing processes to address it collaboratively.” In other words, the blood-system buck doesn’t stop at any definitive place.

Blood Watch is not giving up, says Lanteigne: “Minister Philpott and Prime Minister Trudeau are in for the fight of their lives; there is no way we will stand down on this issue and allow our blood system to be sold off—or that of the sovereignty of our donors—so that a private company can make a profit and exploit vulnerable Canadians.” Bahardoust is confident future licences will be granted: “We are not really concerned on the federal level,” he says.

Back in Ottawa, Philpott ended her questioning in the Senate with a plea to give blood and plasma: “It’s really unfortunate that we can’t manage to get voluntary donations to meet the very serious need for plasma protein products, so I encourage all senators to find ways to donate blood and plasma as soon as possible,” she said. Where Canadians should go to make these precious donations was left unsaid.