Why social media has taken over your life—and you need to sign off now

Jaron Lanier says social media is turning us into highly manipulable addicts. The only solution is for users to pay—and own their own data.

(Shutterstock)

Share

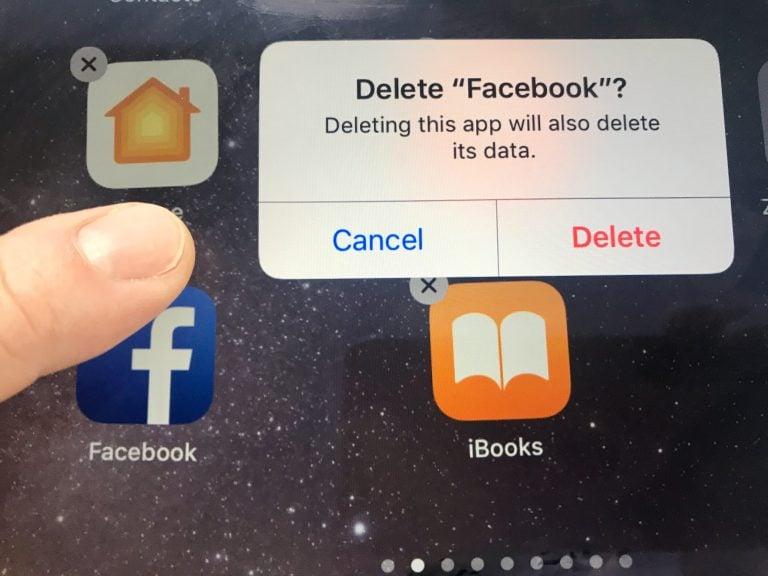

For those who worry social media is running—or ruining—their lives, tech guru Jaron Lanier offers no reassurance. However, he does have a plan. In his wryly titled new book, Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now, Lanier sets out why he believes the likes of Facebook, Instagram and Twitter are making their users more belligerent and less happy, and he suggests an entirely new system whereby the programs are responsible to their users.

Lanier was a pioneer of virtual reality in the 1980s. He now works as a “Prime Unifying Scientist” at Microsoft and is supremely well-connected in Silicon Valley. He insists that social media (along with Google’s YouTube and its algorithmically created video feeds) has a “deleterious business model,” to which he gives the droll, bathetic term BUMMER, or “Behaviors of Users Modified, and Made into an Empire for Rent.” Lanier bemoans his own influence on this problem: in the 1990s, when he worked on scaling up the internet, he was among the advocates for widely distributed free software—which was then monetized through advertising and spawned widespread data-harvesting. But BUMMER isn’t just about collecting data: it seeks to create “engagement,” leading seamlessly, in Lanier’s view, to addiction, and thence to manipulation. Users are driven to think in certain ways by their feeds. What fuels this whole process is the stirring up of negative emotion: When something we read or see online makes us angry, whether it’s a fake-news Tweet or a conspiracy-fuelled video—we engage.

There is hope, Lanier contends, if we delete our accounts—thus withholding our data and disrupting the BUMMER business model. And if users start paying for social media services, Lanier writes, the companies “will serve those users,” rather than the “hidden third parties” who pay for ads—or propaganda—to be shoved in our faces. On the phone from Berkley, Calif., where he lives, Lanier spoke with Maclean’s about why he feels social media is eating away at civil society, and how we might be able to help build it up again.

Q: At the start of your book, you mention that even if people agree with your arguments, they “might still decide to keep some of [their] accounts.” Is it possible to do so without being manipulated?

A: Well, the effects of the manipulation programs in social media on the population are statistical. On average, people do become crankier, more irritable and less happy than they would have been, but there will be some minority of people who do better with [social media]. I feel it’s up to individuals to figure it out. I can say you’re probably becoming a worse person if you use it, and if that’s so, I don’t think there’s any detail in how you use it that can improve that. The system is devious and diabolical, so when it gets you, it’s like [asking] a gambling addict, “Can you still gamble and just be less of an addict?” If you’re starting to see that degradation, it’s very hard to put a Band-Aid on it. You’re just going to have to delete the account. I’ll tell you an example: Elon Musk has gone nutso and, out of the blue, started accusing one of the rescuers of the Thai boys who were trapped in the cave of being a pedophile [a claim he would later retract]. That’s [Musk’s] addiction talking. That’s the same thing that happened to Trump and others who get a Twitter addiction and turn into assholes, which I don’t believe has been Musk’s character in general. He will continue to be one until he deletes his Twitter account.

Q: Not long ago, you praised him for deleting Facebook.

A: Yes. Well, this is the tricky thing: Sometimes people will delete one but stick with another, and that’s why I advocate just deleting them all.

Q: Do you yourself have dummy accounts so you can check some of these services?

A: Well, I have friends who are in top positions in all these companies, so I can just visit them and see the latest stuff they’re doing. In the old days, my cats had accounts, but I don’t even think it’s necessary anymore.

Q: The likes of Facebook do make it hard for you to see anything posted to their service if you don’t have an account. Is there a productive way of using these services without giving too much away?

A: I’ve gotten this question from world leaders and all kinds of prominent people: “Well, I only use social media in this very limited way. Is there a problem?” And yeah, there is. Let’s say you never post on Twitter at all; you just have an account. You’re still under surveillance based on what you look at. If you use any of the Facebook[-owned] programs, including WhatsApp or Instagram or Messenger, you install software that puts you under constant surveillance, and then your data is adding to the machine, where correlations between you and people who have something in common with you are used to try to form better behaviour predictors so that people can be manipulated. The stream of stuff you see [on] the services is still designed to grab, addict and modify you, but also, you’re contributing to that effect for other people.

[There’s a] network effect, meaning that everything’s on Facebook, so everything stays on Facebook. Anybody who’s doing something like organizing a football game for their kids tends to feel they need to be on it, so there’s a practical addiction, and there’s the actual addiction in the brain. Those two things combine to make it very hard to leave these [services]; however, I’m still calling people to leave, for a very practical reason. If everybody’s on this, then nobody can think outside of it. And if nobody can think outside of something, then society is stuck. You have to have diversity of thought. In the past, society has addressed waves of addiction that were degrading our lives, like cigarettes and drunk drivers: political organizers were able to change society for the better by countering those addictions. But you can’t even have the conversation if absolutely everybody is stuck within the addiction framework. Even if a few [people leave], we create that space for the conversation we desperately need.

Q: How about accessing social media via a VPN, with anonymizing plugins on one’s browser—is it possible to not be subsumed by “the machine?”

A: It’s very hard, because Facebook works extremely hard to know who you are. The whole point is to manipulate you, and they can’t do that if they don’t know who you are, so they have access to a vast range of information. For instance, if your cellphone is on, even if you’ve turned off geolocation, you’re still pinging on towers, and different services will combine the pinging from the various carriers to try to isolate where a person is. Of course, you can make some progress; it basically becomes a game of cat and mouse between you and the engineers who are trying to discover your identity at one of the largest companies in the world. You have to be constantly re-evaluating your strategy, and that’s labour-intensive.

Q: In the book, you argue that empathy is being eroded because our feeds are being tailored in certain ways, so different people are being fed different perspectives on the same events, and therefore are less attuned to understanding what others might be thinking or experiencing. Is this exacerbating the political split between right and left?

A: What tends to happen is, the algorithms look for correlations between people. For instance, let’s suppose you and I eat the same breakfast cereal; we tend to like going to the same park, or any random thing. Then it’ll compare us with hundreds of millions of people to find the two million people who have those things in common, and then people who like the same brand of socks. They’ll say, “Well, this person went to the same park and [had] the same education… They kept clicking when we showed them this, so we’ll show the same thing to somebody else who’s like that.” Now, if you iterate on this billions of times, you end up showing the same stuff to people who initially had a little bit of overlap in some data about them, so they start to have more and more overlap.

However, as you said, it’s not that the whole society sees one thing, but rather, it splits into pieces. In the U.S., we’ve seen this extraordinary polarization. It’s a funny thing: The algorithms are trying to modify people based on data, and as that iterates more and more, you do start to bring groups of people into more similarity—and then if the “bucket” they fall in is different than another one, then they’re more and more alienated from that other one. The last time we saw this degree of polarization in the U.S., I think, goes back to the Civil War period. In that case, the difference was based on geography and background and the means of economic livelihood: all physical-world stuff. And in this case, for the most part, the polarization is artificial: people who have similar interests and experiences are being convinced they’re entirely separate.

Q: And yet, everyone has opinions on the same things and the same people—such as Donald Trump.

A: Well, Trump couldn’t have been president without the social media addiction process. His mere existence as president is created by Twitter and the way it can be used by people trying to disrupt society, meaning specifically Putin’s intelligence agencies.

We have people who are brought under a common umbrella of a media feed designed to addict and manipulate them, and if they’re in the same bucket, they have a bizarrely common set of reference points. In the past, if people watched television, they still had a broader range of experiences during the day, but people are constantly connected to their phones, so if they’re in the same bucket and receiving the same feeds, then people can have an artificially created commonality of experience and outlook that’s not characteristic of previous times, unless you’re living in a police state like North Korea or [under] the Stasi.

Q: The solution you prescribe is to have people pay for social media, and to give them ownership of their own data, which they may provide in exchange for reimbursement. To what extent is this idea being taken up?

A: It seems to have gained currency, so to speak. I’ve gotten contacted by hundreds of start-ups that are trying to do some version of it or other. It’s been talked about by regulators in Europe, and it suddenly is in vogue in some of the big tech companies, too—not just Microsoft, but also Tim Cook from Apple has expressed similar ideas. It’s really an interesting time.

Q: Is it possible that our habit of providing data to big companies on our smartphones could be turned into something redemptive?

A: You mean, am I hopeful that this era will inspire people towards something better, to make use of their phones in a more positive way?

Q: Sure.

A: A lot of the reasons people were attracted in the first place to smartphones and to social media—which are two distinct things—are perfectly valid, and a lot of good stuff happens. If people can find a way to make it through being parents of a little kid by connecting with other parents, or if people with unusual diseases can find each other and share experiences, that’s great. Of course we should celebrate those things. What I hope is that as people start to notice the super-extreme concentration of wealth and power among the people who run the biggest computers, and as they start to see the strange way that social safety nets are being undone and there’s a rise of xenophobia all over the world at once, they’ll realize that these two processes are the same process. At the same time, they hear from Silicon Valley that artificial intelligence and robots are going to make their jobs go away, so the only people who matter own and run the artificial intelligences and robots, and everybody else will just be grifters, hanging on if they can. They have to understand that that whole world runs on data that’s being stolen from them. If they started getting paid for what they’re doing with their phones, and to pay for what they enjoy on their phones, that transition would make everybody’s life more honest, straightforward and dignified.