Why your sustainable tuna may still be unsustainable

Rewarding fishermen for their sustainable catch, while allowing them to fish unsustainably, dupes consumers into supporting companies that take part in bad behaviour

The tuna vice holds a tuna head. (Photograph by Nick Iwanyshyn)

Share

(Pixabay)

This piece first appeared at The Conversation.

Tuna is one of the most ubiquitous seafoods. It can be eaten from a can or as high-end sashimi and in many forms in between. But some species are over-fished and some fishing methods are unsustainable. How do you know which type of tuna you’re eating?

Some tuna is certified as sustainably caught by groups such as the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) that set standards for sustainable fishing. But these certifications are only good if they are credible.

In late August, several media outlets published stories about On the Hook, a new campaign by a consortium of retailers and academics who have taken issue with some fishing practices allowed by the MSC. As a university professor whose research focuses on private seafood governance, including certifications and traceability, and fisheries policy, I am deeply familiar with the issues at hand. I support the campaign, but don’t stand to gain from the outcome.

The Western and Central Pacific skipjack tuna fishery is one of the world’s biggest. Some of the tuna caught here carries the MSC’s blue label, identifying it as the best environmental choice for consumers. But the same boats making that sustainable catch may also use unsustainable methods to catch unsustainable fish on the same day.

The On the Hook coalition sees this as at odds with the MSC certification, as do I. Yes, sustainable and unsustainable fish can be separated; there are people on board whose sole job is to do this. But rewarding fishermen for their sustainable catch, while allowing them to fish unsustainably, dupes consumers into supporting companies that take part in bad behaviour.

Does sorting work?

The On the Hook campaign singles out one fishery in particular: the “purse seine” fishery in the tropical western Pacific Ocean. This fishery covers the waters of eight island nations, including Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. Under the Nauru Agreement, these nations, usually referred to as the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA), collectively control access to about one quarter of the world’s tuna supply.

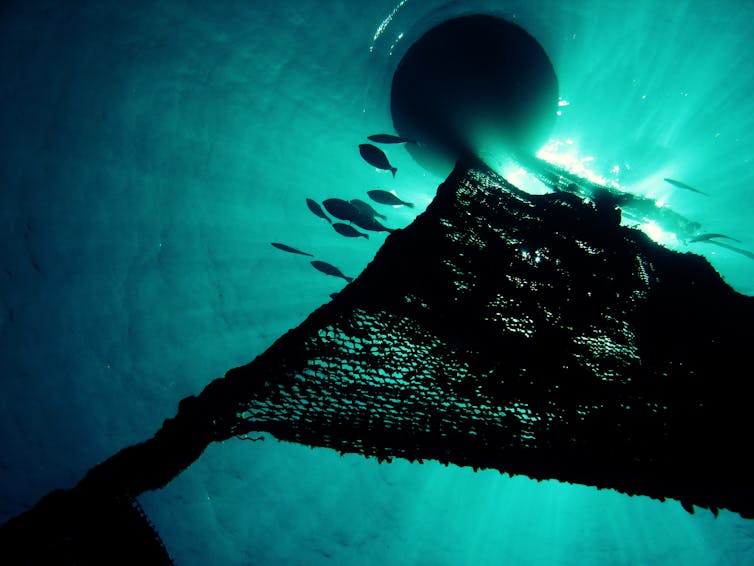

Fishermen can use nets to catch free-swimming adult tuna and earn MSC certification for their catch. But these same fishermen can also use fish aggregating devices (FADs) — instruments that attract all kinds of marine life, including adult tuna, juvenile tuna and hundreds of species of sharks, turtles and other fish — to net their catch. Fishing on FADs is faster and less costly, but these devices are associated with high levels of bycatch, one of the main sustainability concerns in many fisheries. Fishing on FADs does not earn MSC certification.

(Shutterstock)

Under normal operations, the fishermen use both methods. “Compartmentalization” is a technique that allows the unsustainable portion of the fish to be separated on board the vessel from the sustainable portion. This is supposed to provide assurance to consumers that they are making a sustainable choice. Yet the negative environmental impacts connected to FAD fishing operations should surely also be considered in an MSC assessment. Currently, this does not happen.

Compartmentalization remains necessary because there isn’t enough of an economic advantage for companies to make only sustainable catches. It costs fishermen more to fish sustainably because they have to find the tuna, instead of waiting for it to come to the FAD.

A fleet using both methods can be part of a higher value premium market and earn financial security from the high volume, yet unsustainable, fishery. If purse-seining tuna vessels need to subsidize their sustainable fishing with unsustainable practices, then MSC certification has not provided the incentive it set out to.

A holistic fishery

Millions of tonnes of tuna have been fished from the waters of the Western and Central Pacific fishery. But the countries controlling these waters have not benefited to a large extent, mostly due to a lack of cooperation in bargaining for benefits, which allowed distant nations to exploit the fishery.

In the past decade, these Pacific Island states have increased their bargaining power in regional negotiations by implementing a scheme that controls the number of boats that can enter their waters. Under the program, called the vessel day scheme (VDS), these countries can now charge higher fees to boats that want access.

For example, PNA countries used to extract between three per cent and six per cent of the value of tuna fishery in their waters. Since their bargaining power has increased, they can now extract more than 14 per cent of the value, and this number is likely to continue to rise.

This is no small accomplishment for these Pacific Island nations, and other coastal state collectives are now trying to emulate their success. But this does not mean that all of the practices they allow are commendable, including those that are not representative of the “best environmental choice” in seafood.

On my Facebook feed, a colleague recently commented: “A Pacific Islander owned sustainably certified fishery is the wrong target.”

Let me clear up this misconception. The On the Hook campaign is not targeting the PNA, but the MSC. It would like the MSC to delay the recertification — authorized by the accreditation body in September — of the PNA fishery until the compartmentalization practice has been addressed. The fishery needs to be considered holistically.

(United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization/Danilo Cedrone), CC BY

For example, the MSC could specify that to earn a certification, a boat cannot fish sustainably and unsustainably on the same fishing trip. Consumer dollars should not be supporting the very practices the MSC condemns.

Another colleague remarked that because the PNA is challenging big industry, the On the Hook campaign might benefit big industry and hurt the PNA. In fact, it is the same boats, the same fleet, the same companies that are fishing MSC-certified tuna and on FADs.

Muddy waters

My colleagues also worry that the campaign calls into question the credibility of the MSC label. But this has actually become commonplace, with many groups pointing at examples of certified fisheries that are not sustainable. For example, the WWF has recommended that seafood buyers should stay away from MSC-certified Mexican tuna.

I would argue that the MSC is tarnishing itself by normalizing the practice of compartmentalization. It is no longer clear that fish carrying the MSC label offer the best environmental choice. Many Canadian fisheries, like lobster, herring, and Atlantic redfish, are MSC-certified. The faltering credibility of the MSC is a major risk for Canadian fish harvesters who rely on the MSC label to communicate their good fishing practices.

Additionally, Canadian consumers who are used to searching for the blue MSC check mark when they shop for seafood can no longer do so thinking that the logo conveys accurate information. Consumers need to know that the waters are muddy, that seafood sustainability is a moving target, and that it is not easy to make the right choice when standing in the aisle at the supermarket.

Governments and businesses need to make that choice easier for consumers. And they could start by dealing with compartmentalization in the PNA fishery — and elsewhere.

The PNA countries could also make demands. They could allow access rights only to vessels that agree to drop the practice of compartmentalization and that are transparent about their fishing practices.

More than anything, the MSC needs to take a good look at itself and remember what it is supposed to represent — the best environmental choice — not consumer confusion.

Megan Bailey, Assistant Professor, Canada Research Chair, Integrated Ocean and Coastal Governance, Dalhousie University