Women need health and dental care to stay out of prison

A new study reveals that basic health care, both in prison and on release, is essential to ensure successful reintegration into society

Dentist with microscope glasses during a root canal intervention. (Alejandro Moreno de Carlos/Stocksy)

Share

This piece first appeared at The Conversation.

“What I have done is not who I am. Most of us are emotionally and physically wounded. It’s not easy getting out and starting over. We need help, don’t just throw us out into society.”

This testimony from a woman in the Alouette Correctional Centre for Women describes a problem many face on release from a provincial prison. They have no safe place to go — no welcoming family, no home, no job, no community to support them in establishing a healthy crime-free life. Many have untreated chronic health conditions — including diabetes, high blood pressure, cancer, hepatitis C and HIV/AIDs — and mental health challenges stemming from severe abuse in childhood. Likely they have no family doctor.

When you haven’t seen a dentist in years and your mouth is missing teeth, it can be hard to impress at job interviews, hard to find work. When you have chronic pain in your mouth after years of using a crack pipe, it is tempting to seek comfort through illicit narcotics — from the street.

It is not surprising then, that 40 percent of women return to provincial prison within one year of release. Or that a staggering 70 per cent are back behind bars after two years.

A new study from our research team at the Collaborating Centre for Prison Health and Education at the University of British Columbia reveals that basic health care, both in prison and on release, is essential — to ensure successful reintegration into society.

Asking women what they need

In British Columbia, the population of women prisoners is on the rise. The number of women incarcerated each year has increased 20 per cent between 2012 and 2015. There have been few studies to date on the rates of return to prison among the female prison population. There is research that evaluates the effectiveness of substance abuse programming, investigates risk factors for return to prison and the effectiveness of community-based after care. None have examined the role of health-related factors.

Our research study, Doing Time, began with participatory health research forums held within the Alouette Correctional Centre for Women. In these forums, inmates gathered informally to talk about their life trajectories and what their hopes for the future were. They are described in more detail in our book, Arresting Hope.

![]()

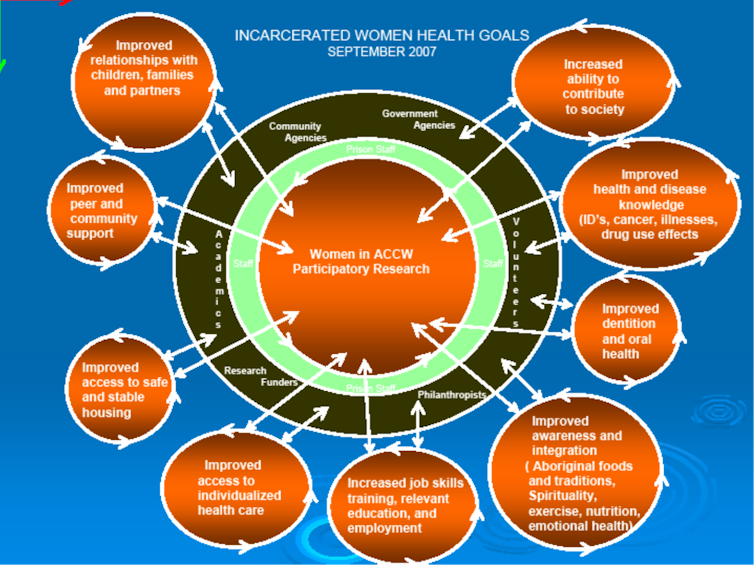

Inmates also identified the health and social goals they believed would help them transition successfully into the community.

Author provided

These goals included: 1) improved relationships with children, family and partners; 2) improved peer and community support; 3) safe and stable housing; 4) improved access to primary health care; 5) increased job skills and relevant employment; 6) more exercise and better nutrition; 7) improved dental care and oral health; 8) improved access to health education; and 9) increased ability to contribute to society.

Interviewing women in the shadows

We interview 400 women about their progress towards these goals, at the time of release from BC Corrections facilities, between 2008 and 2010. We conducted follow-up interviews with 207 of them at three month intervals. The interviews were conducted by peer researchers who themselves had been formerly incarcerated. Each peer researcher attended a workshop on interviewing skills, guided by a manual and supported by a video we created entitled Women in the Shadows.

Most of the women interviewed had only a high school diploma or less and only 10 per cent were employed. Seventy per cent were homeless. Over half the women in the study reported Indigenous ancestry. The average age was 34. In almost half of the interviews, women indicated that they had engaged in criminal activity during the preceding three months.

Why do women return to prison?

The study tested over 100 social, demographic, criminal and drug related factors as well as progress related to the health goals. Significant predictors of criminal activity included: not having a family doctor, depression, not having children, having less than a high school education and incarceration for theft under $5,000 or for a drug offence.

They also included poor general health, treatment for hepatitis C, lack of opportunity to learn about health, poor nutrition, poor spiritual health, not having a dentist and use of marijuana or cocaine.

In prison, women receive only emergency health care. Emergency dental care often involves extraction of teeth, rather than restorative care. Missing teeth are a strong deterrent to a successful employment interview. Crack pipes damage teeth, causing women to suffer chronic pain, which fuels a desire for comfort through illicit narcotics.

Author provided

Treat the addiction, eliminate the crime

The majority of the women interviewed had chronic health conditions, including diabetes, high blood pressure, cancer, hepatitis C, HIV/AIDs, depression and anxiety. Less then one third received treatment during prison. Poor health among incarcerated women has been well documented, with high rates of mortality, mental health disorders, substance use, communicable disease and injury.

Substance use, lack of transportation or medical insurance and night-time work contribute to neglect of health prior to incarceration.

Sexual and physical abuse in childhood and adulthood contribute to mental health disorders which, in turn, lead to self-medication and entry into the drug and sex trades. “Treat the trauma and you will treat the addiction. Treat the addiction and you will eliminate the crime,” is a phrase we use in the Doing Time study, over and over.

In Canada, it costs $116,000 per year to keep a woman in prison and $21,000 per year to supervise her parole. Access to a primary care physician, a dentist and nutrition counselling are powerful protective factors against re-engagement in criminal activity.

These are simple solutions that every woman has a right to. It is time to integrate primary and preventive health care and education into our criminal justice system.

Patricia Jansen, Professor of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia; Mo Korchinski, Researcher in Prison Health, University of British Columbia, and Ruth Elwood Martin, Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of British Columbia