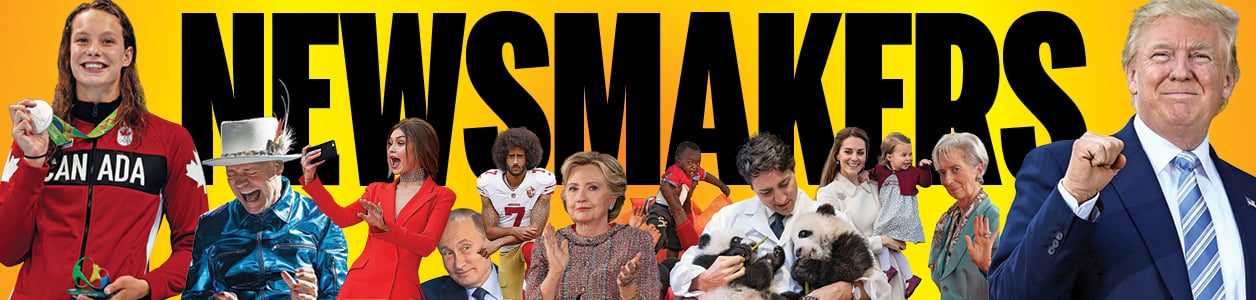

Newsmakers: Penny Oleksiak, Canada’s champion

One day she was just another Canadian teenager—the next, Penny Oleksiak was an Olympic powerhouse

Canada’s Penny Oleksiak smiles after winning the gold medal and setting a new olympic record in the women’s 100-meter freestyle during the swimming competitions at the 2016 Summer Olympics. (Lee Jin-man/AP)

Share

Our annual Newsmakers issue highlights the year’s highlights, lowlights, major moments and most important people. Read our Newsmakers 2016 stories here, and read on to see why Penny Oleksiak made the list as one of our seven Newsmakers of the Year.

Mere days before Penny Oleksiak flew off to Rio de Janeiro for the Summer Games she was a normal 16-year-old out shopping with friends and trying to haggle for discounts at Lululemon by saying she was a member of Canada’s Olympic team. The salespeople were having none of it. Oleksiak wasn’t just an unknown in the world of Olympic sports; she couldn’t even point to any success at the Pan-Am Games in Toronto a year prior, because she didn’t make the team.

It took only one week in Rio for Oleksiak to write herself into the history books. Her first piece of Olympic hardware came when she anchored Team Canada to a bronze medal in the 4 x 100-m relay, ending a 40-year medal drought for the country in that event. A day later, she added a silver medal—this one all for herself—in the 100-m butterfly. It marked the first time in 20 years a Canadian woman won an individual medal in an Olympic swimming event. Next came another bronze, thanks to Oleksiak anchoring Canada’s 4 x 200-m freestyle team.

With three medals around her neck and her best event yet to come—the 100-m individual freestyle—Oleksiak probably should have been focusing on getting some rest, like she promised her coach she would, instead of using Snapchat to catch up with friends back home into the wee hours of the morning. Indeed, in the first part of her 100-m freestyle swim, held a day later, her coach and friends could be forgiven if they thought Oleksiak’s late nights online had caught up with her. In the eight-women final Oleksiak was well back in seventh place at the halfway point. Her six-foot-one frame was a full body length behind the leader—surely an insurmountable gap to overcome against the sport’s elite. Then the swimming world came to learn of Oleksiak’s closing speed. As her childhood coach stressed to her from her earliest meets: “Finish your races. It’s all about the back half,” Gary Nolden recalls telling her. “Anybody can blast it out in the front, but what you do in the back half shows your training.”

In the most memorable and nerve-wracking sprint in Canadian swimming history, Oleksiak’s closing 50 m was nearly a half-second faster than her second-fastest challenger. When she touched the wall, she was so gassed it took more than 20 seconds for her to catch her breath and look up at the scoreboard. But when she did, she saw that she had won a gold medal and set an Olympic record in a tie with American Simone Manuel.

Not only did Oleksiak become Canada’s first swimming gold-medal winner since Mark Tewksbury in 1992, she earned the title of youngest gold medallist in the country’s history: 16 years and 59 days old. And the four medals around her neck from one Summer Games puts her alone atop the Canadian Olympic record books.

“I think if she went back to Lululemon now, she would [get a discount],” says Alexis Bragman, another close friend from the Toronto Swim Club.

They might even think it wise to pay her for the privilege.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Newsmakers 2016″]