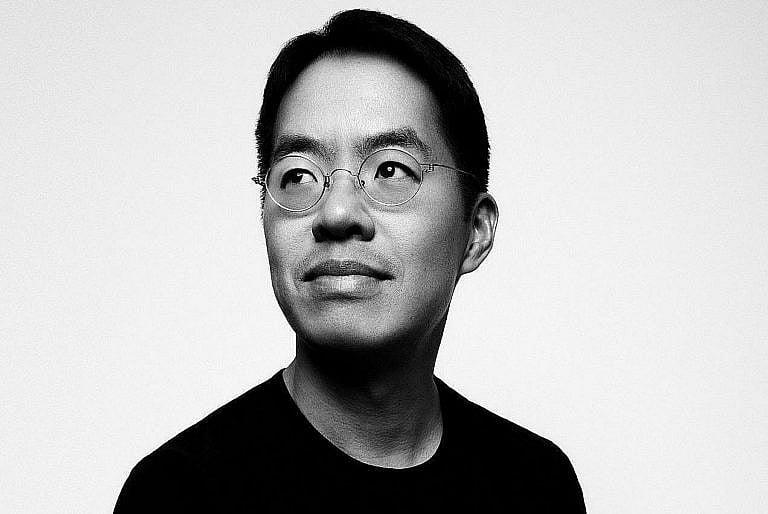

Vincent Lam has worked on the frontlines of Canada’s opioid crisis. It haunts him.

“Some patients stopped treatment, overdosed and died. Those cases will always be with me.”

(Photography by Wade Hudson)

Share

In his Giller Prize–winning short story collection, Bloodletting & Miraculous Cures, Toronto physician Vincent Lam took readers behind the exam-room curtain and into the hectic, heart-straining lives of young doctors. His fifth book, On the Ravine, out this month, plunges readers into the opioid crisis, via two of Bloodletting’s most memorable characters. One of them is the considered, compassionate Dr. Chen—thought to be Lam’s alter ego—who is determined to save his patients, no matter the personal cost.

It’s a dynamic that Lam knows well. In 2013, as opioid use exploded across Canada, he pivoted from emergency medicine to addictions and, in 2017, opened Toronto’s Coderix Medical Clinic. There, his team takes a two-pronged approach to substance-abuse treatment: pharmaceuticals and therapy. Lam believes the problems proliferating in Canada’s ERs and addictions clinics—crowded waiting rooms and lack of consistent access to GPs—are intertwined. Regardless, he is determined to provide quality care, to his patients and himself.

Would you use the word “crisis” to describe the current rates of opioid abuse around the world? The situation seems dire in On the Ravine.

The number of deaths has certainly been increasing, but I’m not sure when you officially declare a crisis. Every single death is a tragedy. My concern is that if we only think about the current situation as acute, our treatments will be knee-jerk. There’s danger in thinking that after some dramatic intervention—like medication or a costly rehab stay—everything will suddenly be better. Those can help, but they’re just steps in a long journey.

Much of Dr. Chen’s life seems drawn from yours, from his love of cycling to his experience of regularly running into his patients on the streets.

I definitely identify with the characters. I know Toronto and I know addictions medicine. One character even has a shoulder injury, and I’ve had recurrent dislocations. And I rarely attend a public event on addictions where someone doesn’t tell me about their own past issues or the ongoing struggles of loved ones. In the book, I wanted to explore what happens when you try to help people when you’re not sure what the right boundaries are.

Caring for patients with addictions can involve cyclical disappointment—they come to you wanting to change, then repeat behaviours. Does that keep you up at night?

I have three kids—ages 12, 15 and 17—so I’m exhausted by the end of the day. But I do think about my patients, past and present. Some call from time to time to let me know that they’re doing well. Others stopped treatment when I felt they weren’t ready and subsequently overdosed and died. Those cases will always be with me. That’s the price of caring for patients. When things don’t work out, I partake in their pain.

How do you take care of yourself?

Some of my self-care is simple nuts and bolts: a healthy daily routine, a reasonable diet and physical activity. The other piece is understanding boundaries. Every physician needs them, but they’re especially necessary in addictions work.

Because patients push them?

Every single day. I don’t share my home or email addresses with them, and I’m careful with social media. Sometimes, a patient will say, “If you don’t prescribe what I want, I’ll have to steal something to get the drugs I need.” I’ve had many patients make harmful choices, even after I gave them exactly what they wanted. No matter what I do, they still have the responsibility of choice.

How else are your boundaries challenged?

I’ve spent lots of time with patients after hours, when I should have been at home making dinner. People have tried to intimidate me by detailing their criminal histories. I’ve had patients flip the table in my office and smash the clinic’s front window. I’m usually not frightened in the moment, because I understand that these behaviours have roots: they may be a way for a patient to feel powerful when they otherwise feel helpless. These are uncommon occurrences, but they’re hurtful. I’m a human being. I don’t get to switch that on and off.

So caring is hard, but not caring isn’t the answer. How do you reconcile that?

It’s a constant calibration for anyone who’s trying to help someone with a substance issue. Health-care professionals, families and friends all struggle with feeling that they’ve simultaneously not done enough and done too much. The most important thing they can do for a loved one with an opioid-use disorder is remain involved in their life.

So the tough-love idea that you should kick addicts out and let them work things out on their own—

It’s not a good model. It’s difficult to know how to love someone and how to set limits. But cutting people out and saying “Come back when you’re better” is not a successful strategy.

Do you have any advice for those families and friends?

The person with the substance-use disorder is responsible for their own decisions, but loved ones still need to figure out what role they can play in their lives. That’s the part they can take responsibility for.

Was there a single incident that made you switch from emergency medicine to addictions?

It was a gradual change. I worked in emergency medicine for 13 years. I really enjoyed it, but it was difficult to always be opening the curtains to a new relationship, having to win trust and then not knowing how things would turn out. I was also seeing the significant burden that opioid use had on the medical system.

When did you realize opioid use in Toronto was at a tipping point?

There were many moments. We hoped that making opioids more tamper-resistant could change the problem. That’s not what happened at all. In some cases, people shifted from short-acting drugs, like Percocet and OxyContin, to street heroin. Then fentanyl began to displace heroin. Now we’re in a situation where we don’t have any great answers. I don’t think any single solution will solve it.

What prompted you to treat your patients’ addictions at the root?

Pretty early on, I understood that simply prescribing medications wasn’t going to be a solution for the majority of people. The roots of substance-use disorders are typically far deeper and far older than the substance use itself. At my clinic, we combine pharmaceutical treatment with therapy. I’ve also seen that the people who tend to get better have something they want to be doing—not a big flashy thing, just “I want to keep studying” or “I want to stay at my job and see my co-workers.”

What are some systemic changes you’d like to see in how addictions are treated in Canada?

Addictions become a crisis when we don’t have access to good pain management and mental health care. The absolute top priority is to make sure everyone has access to a family doctor. In Ontario, medicine is an array of disconnected services. If you have a mental health problem, you may or may not have a GP. If your family doctor feels you need additional support, they might struggle to get you a counsellor, because everyone is working independently. Also, if at some point you visit a detoxification facility, they probably won’t communicate with any of your existing professionals.

What can be done?

We should demystify addictions training in the med-school curriculum for family physicians and fund in-patient addictions care in hospitals. We also need to think much more about prevention, especially in post-injury care, where people are often prescribed painkillers. Canadians should have access to physiotherapy and occupational therapy that’s covered by insurance, plus work policies that give people paid leave to recover from injury or pain.

Are you optimistic that we can make these changes?

There’s no easy fix, but the good news is that everything we have to do is within our medical expertise. We do need political and financial support, though.

What do you think Canada’s politicians are getting right (or wrong) on the issue of addiction? I’m thinking of Pierre Poilievre’s negative stance on safe-supply programs.

Politicians are feeling pressured to take sides, but that doesn’t mean it helps the system. It’s not helpful for Poilievre to call safe consumption a failed experiment launched by “woke Liberal and NDP governments.” I would point out to him that it’s within the normal practice of medicine to innovate ethically, to try things that are off-label—meaning, not yet supported by clear data—and then evaluate critically. Doctors used to prescribe medicated cigarettes as a treatment for asthma.

What about B.C. premier David Eby, who proposed involuntary treatment for people who’ve experienced multiple overdoses?

I agree with Vancouver physician Paxton Bach, who said, “The evidence around compulsory treatment is pretty clear, especially short-term treatment, that it’s largely ineffective and might actually do more harm than good.” I don’t think the issue is that there’s an abundance of high-quality, easily accessible in-patient treatment spots in Canada and patients just aren’t willing to go. It’s quite the opposite. We need to be mindful about politicizing a medical issue. We wouldn’t want MPs to decide whether we should have experimental cancer treatments.

Where do you stand on safe supply, giving people with addictions safe access to drugs?

It’s a thorny issue. I feel more comfortable with the alternate terminology: the public supply of addictive drugs, or PSAD, which is a harm-reduction approach that distributes pharmaceutical-grade drugs to reduce reliance on illicit supply. Advocates come from a place of wanting to help, but we don’t yet have clear evidence that PSAD reduces overdoses and deaths. We do have very good evidence that buprenorphine, methadone and sustained-release oral morphine can. I use them in my clinic.

We sometimes hear the argument that addicts don’t deserve quality medical care—even from doctors themselves. Some even use an acronym: GOMER, or “get out of my emergency room.”

Some patients have told me that they’ve been treated differently once a doctor learns they receive methadone or another addictions treatment—that they were somehow “less kind” to them, which is hugely problematic. They say the judgment can be wordless but distinct. Medical workers won’t say patients don’t deserve health care. It will be more along the lines of “They have to want to help themselves.” Everyone has the right to health care.

You’ve written that doctors are not so different from their patients. How so?

We’re all driven by the same fundamental desires: we want to feel like we belong. We want to have our basic needs met, like food and shelter. And there are things we all want to avoid, like fear and anxiety. Trying to move away from those two things is a fundamental reason people turn to opioids.

Have you ever taken opioids yourself?

I had appendicitis during my first year of medical school and was prescribed Tylenol 3s. Fortunately, I don’t recall them being especially pleasurable. I’ve taken care of patients whose serious problems started with codeine.

How do you handle the grief that comes with losing a patient?

Of course it impacted me when patients died in the ER. But in addictions, I take care of people for months and years—some for almost a decade. So it’s much more personal now. I acknowledge my feelings of sadness, loss and failure. I give them room within myself. I also train younger physicians, help to write new addiction guidelines and work on improving my own practice. I ask myself, “What can I do to make this situation better?” I see my colleagues struggle all the time. I encourage young doctors to do other types of work as well, for balance.

What has doing this work taught you about humanity?

Well, that’s a small question. I’ve learned that for most people, every decision they make seems reasonable to them in the moment. But when those things become repeated and ingrained, they can cause someone a great deal of harm.

Do you ever see patients get better?

Absolutely. Those cases speak to the human capacity to make hard choices that are true to oneself. It’s an incredible thing to witness people imagine a change they want in their life and to provide the support they need to do it. In some ways, this is the most satisfying work I’ve ever done.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This article appears in print in the February 2023 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.