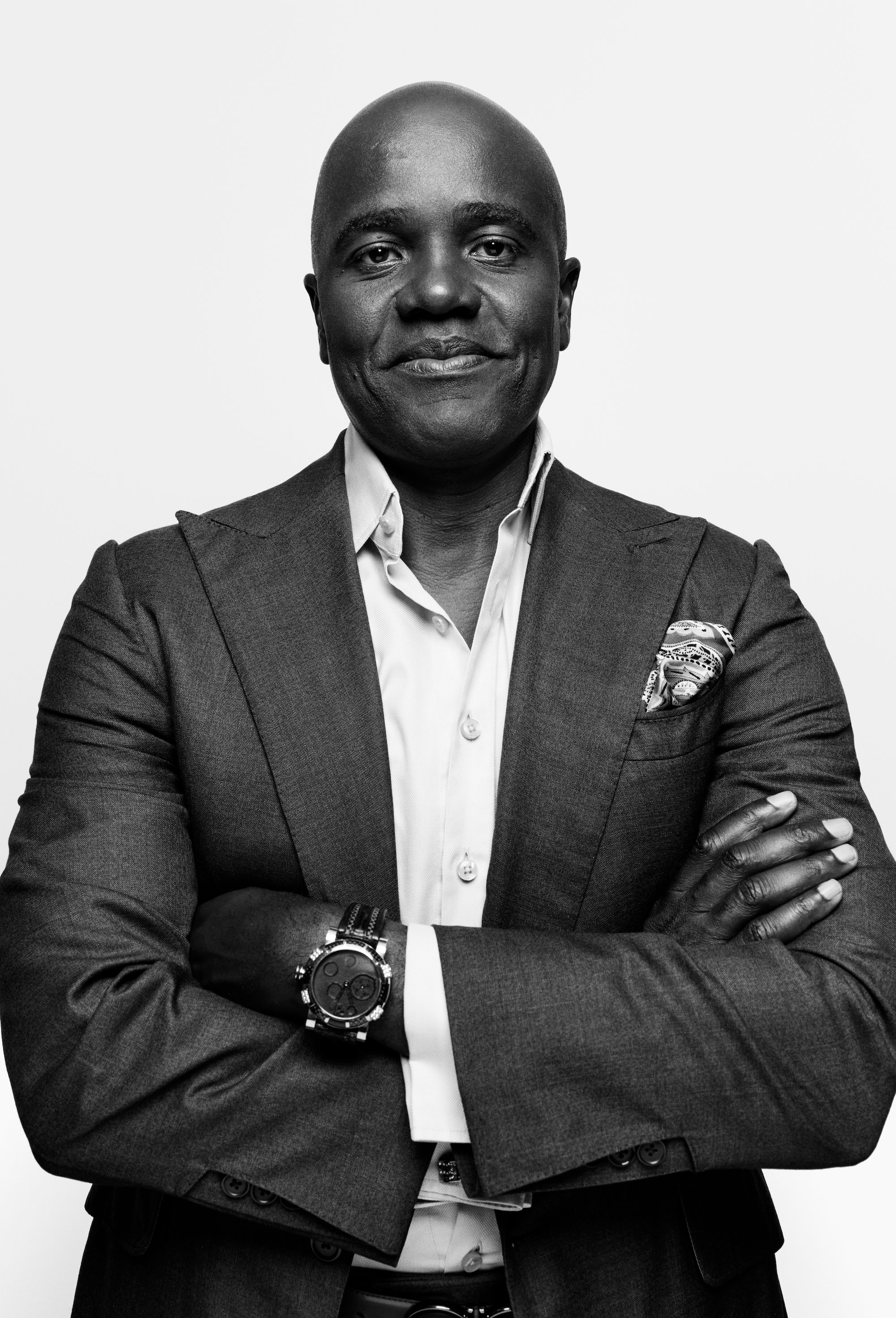

Why Wes Hall is betting on Black entrepreneurs

On Dragons’ Den, he’s known as “The Fixer.” That nickname holds true in real life, too.

(Photos by Wade Hudson)

Share

Don’t let the fancy suits fool you. For Wes Hall, the self-styled “King of Bay Street,” and the first Black Dragon on CBC’s Dragons’ Den, the path to success has been hard-won. He grew up with his 14 siblings in a tin shack under the care of his grandmother in Jamaica, immigrating to Canada at 16. He then worked as a cleaner and a chicken catcher before breaking into Bay Street as a mailroom clerk. Later, Hall amassed his fortune by counselling companies contending with hostile takeovers as founder of the shareholder services firm Kingsdale Advisors. In his new memoir, No Bootstraps When You’re Barefoot (out October 4), Hall details the experiences that shaped his journey to becoming one of the most influential forces in Toronto’s Financial District.

Among the Dragons, he’s known as “The Fixer,” and that nickname holds true in real life, too: In 2020, Hall founded BlackNorth Initiative, an organization that is working to dismantle anti-Black racism in the business world, inspired by the racial tension that plagued his early career. Now back in the Den for a second season, Hall shares his thoughts on the meaning of making it big, and the faith, family and fortitude that guided him through it all. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You’ve said that Bootstraps isn’t supposed to be like other typical how-I-made-it, instruction-manual memoirs. How so?

When you read those kinds of books, it’s like, “Okay, here’s the step-by-step.” There’s nothing in my book that specifically shows readers how I became successful; it’s about the struggles I went through. The things I experienced as a child defined the person that I became: the father, the husband, the philanthropist and the businessperson. Without those experiences, would I have started BlackNorth, an organization that helps other underserved people? Would I have been a good dad? Even though those times were painful, I learned some important lessons from them. The book is about taking chances and never feeling sorry for yourself.

When did you realize you had made it?

When I was making Wes, the 2016 documentary about my life, and when I was writing this book. I saw all the pieces of my life put together and went, Man, this shouldn’t have happened to me. I shouldn’t be here.

What does “making it” mean to you?

When my wife and I started having kids, I remember that she would ask for more diapers, and I didn’t have the money to buy them. Those were not comfortable conversations to have. Now, when I can stay in a five-star hotel and not have to worry about paying the bill at the end, that’s comfortable.

You write that success truly came for you when you started letting your faith shape your life.

I talk in the book about being a Jehovah’s Witness, and knocking on people’s doors. That gave me a thick skin. It also taught me that I have a calling that’s bigger than just myself.

Do people ever open their door and say, “Wes Hall? What are you doing on my front porch?”

I get a little bit of that. But Prince and Michael Jackson were Jehovah’s Witnesses. So are the Williams sisters. Those people are way more recognizable than me.

How have your life experiences shaped the way you approach contestants on Dragon’s Den—particularly Black contestants?

If all the Dragons look the same, they’re not worrying about diversity. But once the Dragons look different from each other, people start to think that maybe the people in front of the panel should be just as diverse. I’ve supported a number of BIPOC entrepreneurs, even outside of the show. One is a company called BIPOC Executive Search, which develops leadership in communities of colour.

Kevin O’Leary was the adversarial pot-stirrer on the show. What’s your Dragon schtick?

My thing is to support the underserved—entrepreneurs who go to the traditional funding avenues to get capital and are essentially laughed out of the joint. A lot of the Dragons say to the contestants, “You’re not an entrepreneur.” If you have the guts to start a business, you may not be as successful as someone else, but you are an entrepreneur. I’m not a mean Dragon.

How have the racial dynamics of Bay Street changed since you started frequenting big boardrooms?

Change is very slow. I’ve been on Bay Street for 30 years, and I think that people now might not get the kind of opportunity I got way back then.

It’s hard to believe that things are somehow worse.

Companies are now looking at resumés very, very closely, and saying, “Well, they went to this school, and they have these relationships and connections.” We’ve regressed a little bit. For Black entrepreneurs, there’s still a lack of confidence among investors that we’re capable of building businesses. When I started Kingsdale, I couldn’t get anyone to get back to me, and the same attitude exists in the executive suites today. A lot of people just don’t want to bet on us.

You’ve talked about the fact that Canadian companies typically don’t collect race-based data. Why is that a problem?

A lot of companies say, “We’re not going to collect it, because we don’t want it to look like we’re discriminating against somebody.” But if you don’t know the makeup of your organization, how else are you going to know whether you’ve made progress? If, as a business owner, I’m saying I would like to have a diverse organization, why wouldn’t I want to collect statistics that will help me increase that diversity?

Has the Great Resignation reached Bay Street? Are people seeking more balance?

I see it, but I don’t really think it has the same impact on Black and Indigenous people. If they finally get hired into the C-suite, they’re unlikely to go to their bosses and demand that they be allowed to work from home. People of colour could really take advantage of this dislocation in the workforce by not making the same demands as people of privilege—people who take their access to jobs for granted.

It’s been a long road, but you’ve got the nice house, the nice car and a great family. Is there anything else that you would like more of?

I’d like to do more philanthropy. There are communities in Canada that are in extreme poverty. I’d also like to do more in Jamaica, in areas like the one I come from, where there are zero jobs.

What’s stopping you?

Unfortunately, it’s the time factor. Once you get to a certain level in business, you get pulled in so many different directions. People see the benefits of having you associate with what they’re trying to do. You can’t say yes to everyone. I’d love to have more time for the things that I enjoy.

How does the King of Bay Street spend his off time?

In the summer, I like to spend a month with family, travelling to parts of the world we haven’t seen before. I read a few books and think about all the different business ideas I have, and how I can get started on them.

Can you give me an example?

Last time I had an idea that was really out of my comfort zone, I ended up owning the Harbor Club resort in Saint Lucia. I’m still dealing with it, actually. I try not to let myself get so bored that I get into trouble.

This article appears in print in the October 2022 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $8.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $29.99.