My excuse was youth. What’s theirs?

Barbara Amiel on why mental illness can’t be treated with legalities

Share

Back in the 1960s I had “Charlie.” Charlie was a derelict living in Toronto flophouses. I was a CBC researcher living in a highrise studio apartment. My assignment was a documentary on skid row lives, and Charlie was one of the three winos I had selected. All of them had mental disorders of varying degrees. They heard voices or suffered from paranoia. The day before shooting, Charlie went AWOL, ending up in the drunk tank. I bailed him out on CBC expense money.

Charlie didn’t have a golden voice, but he heard lots of voices and had conversations with them all. He wanted a regular job, he told me. After filming, I bought him a clean T-shirt and took him to a centre hiring hourly labourers. When I came home, an inebriated Charlie was waiting. He preferred working on camera and thought that was his true calling. I took him into my apartment for coffee and a talking-to. Afterwards he left—taking some small sterling silver items of mine.

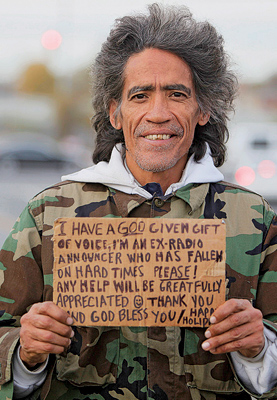

My excuse was plain stupidity and youth. I’m not sure what excuses the enthusiasts behind the golden-voiced, down-and-out Ted Williams who, in a predictable arc after discovery by a journalist, gained worldwide fame, was arrested for an altercation, took part in an intervention on television’s Dr. Phil show, and disappeared into rehab. His sob story was watched by millions, when they weren’t watching people with utterly no connection to victims of the Tucson killings (except nearby zip codes) sobbing their eyes out. Heaven knows, Americans can go on “healing” and “counselling” and “intervening” until every last person is in therapy. But the problem when a popular culture goes barking mad is that complicated problems get reduced to cartoons.

The Tucson murders raise issues that can’t be cured by a “walk for peace,” calls for healing—or gun control. Jared Loughner was demonstrably mentally disturbed. He used a gun to kill six people and wound 14, though he could as easily have driven a truck into that crowd, or a snowplow like the Toronto chap who allegedly went on a 90-minute rampage last week and killed a policeman. Because Loughner had previously given signs of an unquiet mind, demands surfaced for a central registry (in cloudland perhaps) noting symptoms so he could have been prevented from purchasing weapons. Since blame must be assigned, we have the college who didn’t report him to authorities, the police who let him off earlier when he ran a red light, and the man in the moon who must have heard his nightly wailing.

I’d be all for gun control if it would help rather than aggravate the situation—if you could remove guns from criminals or insane people alone rather than those on the side of the angels. But it makes no sense. After all, a life or two might have been saved if someone in that crowd at Safeway’s had had a gun in their handbag.

The passengers on the Greyhound bus travelling along the TransCanada Highway ran like hell as one of them stabbed and decapitated his seatmate, but I doubt if a passenger with a gun would have run, let alone the bus driver if armed. Here in Florida, where I am staying, a bill is proposed to allow the unconcealed carrying of weapons. The thought of encountering visibly armed fellow shoppers at the 7-Eleven store is unnerving at first, but on consideration I suppose it should be reassuring.

How do you deal in advance with people who have mental disorders that may turn violent—short of an Orwellian society? Loughner had no criminal convictions, no hospitalization. There are loads of websites with feedback 10 times more violent and bizarre than his ramblings. In a litigious society, what American doctor would risk certifying anyone incapable of violence and fit to own a gun? What university would risk being sued for reporting a student because they said inappropriate things in class? Was it political correctness, liability worries or both that, according to National Public Radio, suppressed the discussions at Walter Reed Medical Center about perceived paranoid behaviour in Maj. Nidal Hasan, who allegedly went on to kill 13 Army personnel at Fort Hood? Tort reform in America that reduces liability and jury awards would be more help in reducing violence than gun control.

Starting in the 1960s, a deinstitutionalizing movement ended most forcible medicating and confinement of mentally ill patients in Canada and the U.S. The result were Charlies: people unfit to live in the outside world sleeping on streets, wandering about muttering to themselves, or in prisons. Families were wrecked by members who would not take their antipsychotic medication and could not be forced to, except for short periods of time. A reasonable guesstimate was that 98 per cent of people with mental illnesses did not commit violent acts. Should they all be locked up, declared incompetent or rigorously monitored for the two per cent that might? For how long? If the voices tell a person to paint himself blue, what harm to society or himself? How can we know in advance if the same voices will order something violent?

I have no difficulty with a society that makes it hard to lock people up for a meaningful period of time, though I have some difficulty with making it virtually impossible. Getting the right balance is difficult in the best of circumstances. But mental illness is now defined and treated in a defensive legal setting rather than an aggressive clinical one. If this is to continue, there is no point our going beserk when a lone individual does. We must submit to the rule of trial lawyers and legislators and quietly bury our dead.