Writing the stars: 28 years covering showbiz

Brian D. Johnson on the nature of celebrity from Meryl to the Bieb

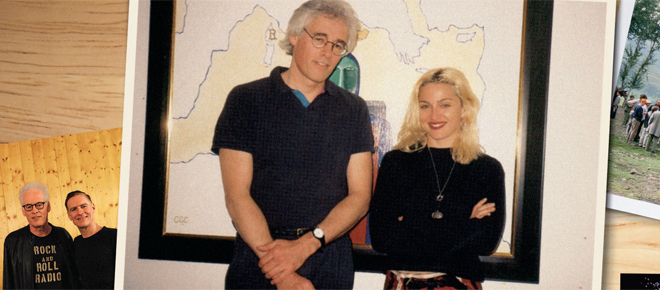

Courtesy of Brian D. Johnson

Share

When I rang the buzzer at the gate of Madonna’s house 25 years ago, she was at the height of her fame. It was the year of the Blonde Ambition tour, many houses ago. She lived in a white bungalow on a cul-de-sac in the hills above Sunset Boulevard. An assistant ushered me into a severely white living room where Madonna appeared unannounced. As she offered a firm handshake, I was shocked by how small and plain she looked. Bleached hair hung limp from dark roots. Scarlet lipstick set off a pale complexion that was less than immaculate. Then I took in the clothes: the red Gaultier pants and a white lace top with bare shoulders that left her nipples visible through the fabric. After the introductions, Madonna promptly covered up with a black sweater, as if exposing her body had just been part of the presentation. Throwing open French doors that led to the pool, she sat down on a gold divan, clipped my microphone to her necklace and said, “So here I am. I’m going to spill my guts and try not to bore myself in the process.”

The assistant disappeared and left us alone for an hour and a half.

Today that would never happen. Sure, some stars still invite Vanity Fair into their home for a full-service interview, but more typically they hold court in the industrialized petting zoo of a hotel media junket. Stacked in a holding pattern like planes on a runway, journalists are fed through an assembly line of interviews, slots of 10 to 20 minutes shaved down to the last second by squads of publicists. It’s not unusual for a handler to sit in the corner of the room, babysitting the message. The face-to-face interview seems arcane in a digital age, this junket ritual of slicing a star into minute portions so everyone comes home with a personalized relic. We talk about “doing the stars.” (“Have you done Meryl? She’s so great.” “I just did Julia. Talk about attitude.”) But now it seems the stars are doing us.

Maybe it’s a good time to be getting out of the game. After 28 years, I’m leaving the magazine. I’m not retiring from journalism, or film criticism (I’ll maintain my blog at Macleans.ca), but I’m stepping away from the machine—both the well-oiled editorial engine that puts out this magazine each week, and the showbiz juggernaut that feeds the entertainment beat. After logging countless interviews, it seems a fitting moment to reflect on a more golden age, before fame became a matrix of marketing, fashion and social media.

The first movie star I interviewed was Michael J. Fox, when he was a 26-year-old riding high on the success of Back to the Future. Meeting on the set of Family Ties in L.A., we chatted during his cigarette breaks, then at lunch he drove me across town in his Porsche, which he drove like a racecar, seatbelt unbuckled. Beer cans littered the floor, a detail my editor agreed to leave out of the story because it suggested he was a drunk. Today no star would leave himself that vulnerable, and no editor would jump to protect him. As Fox told me in an interview last fall, “If they’d had iPhones with cameras when I was coming up, I’d still be in jail.” Just over a year ago I had an audience with the next generation’s young Canadian superstar, Justin Bieber. Granting me a half hour in his dressing room before a show, he impressed me as a polite, serious young man who showed not a hint of the bad-boy antics that would start just weeks later. I felt I’d been played.

“What’s he/she really like?” It’s what everyone asks when you meet someone famous. But how can you know? When I interviewed Robert Downey Jr. for his breakout hit, Chaplin, I couldn’t understand why he was so nervous. The guy was sweating bullets. That was before the world knew that this young genius was a drug addict.

Even with old-school access, the celebrity interview is a sticky transaction, a blind date that demands forced intimacy on an uneven playing field. The star is rich and famous, the journalist is not, yet we pretend to ignore our differences. The journalist is automatically suspect, a sycophant concealing a switchblade. But an actor sentenced to a weekend of robo-interviews may feel his skin crawl with a deeper sense of duplicity. Amid the shared alienation, we look for glimmers of common ground.

One thing you learn by meeting stars in the flesh is whether their charisma holds up. Many look disturbingly ordinary, or short. Mick Jagger and Tom Cruise are tiny. A gum-snapping Cameron Diaz was drab and greasy. Meg Ryan failed to light up the room. But a star can also leave you awestruck when you least expect it. To sit down with an aged, elegant Gregory Peck, and hear the cadence of that Kill a Mockingbird baritone, was like having coffee with God.

There are screen goddesses who radiate palpable divinity even at close range. Among those I’ve met, Jessica Lange, Michelle Pfeiffer, Meryl Streep, Sophia Loren, Juliette Binoche, Uma Thurman, Jodie Foster and Michelle Williams were all luminous. All of them had exceptional skin. Skin doesn’t lie. Nor do eyes. And movie stars do tend to have more light in their eyes than the rest of us. Paul Newman’s electric blues had an intensity no camera could fully capture. Angelina Jolie’s regal gaze can cut through a crowded press conference and melt a journalist at 20 paces. Donald Sutherland’s eyes are so large and liquid they look as if they might devour you. And Harrison Ford’s are exceptionally busy—the stare of a paranoid stoner locked in a perpetual conspiracy thriller, trying to make up his mind if he’s predator or prey.

Ford was one the more anxious subjects I’ve encountered, at least in the first of our three interviews. We were in a Manhattan hotel, and the streets below were jammed by a homecoming parade of troops from the Persian Gulf. When I asked about the war, Ford muttered that he was “appalled.” Then he paused for a full 15 seconds of silence until he finally said it was too complicated to discuss in an interview. He seemed possessed by a mortal terror of sounding inauthentic, and would keep correcting himself, erasing phrases, sometimes crumpling up an entire train of thought and throwing it out. As Ford talked, he fiddled with the glass top of the coffee table, squaring it at the corners, the former carpenter searching for a straight line. “I’m not crazy about interviews,” he acknowledged when asked about his reputed aversion to doing press. “But I don’t hate them. I have an aversion to celebrity. I have an argument with the place that celebrity has in this country and in this culture. There’s just too much celebrity babble out there.” And that was years before the inescapable surveillance of Twitter, Facebook and TMZ.

Ford made a fetish of humility. “I’m in a service occupation,” he sighed. “It’s like being a waiter or a gas station attendant. The guy in the restaurant is waiting on six people; I’m waiting on six million.” By the third time I interviewed him, any nuance of anxiety was gone. He wore a mask of leisurely confidence, as if he’d finally understood that celebrity was just another crazy role to be mastered, a comedy role heavy on charm. It made him less interesting. He no longer acted like an imposter in the house of fame.

Just as Ford acquired a shell persona, celebrity has become a well-armoured citadel, protected by legions of flacks. It was erected during the ’70s and ’80s, as movie stars became absurdly powerful and overpaid. But over the past decade, their salaries have wilted. A single actor can no longer be counted on to “open” a movie with thunderous box-office. And the stars are now being upstaged by their roles: franchise action figures like Batman, Katniss Everdeen and Jack Sparrow wield more power than those who play them. And for the journalist, it’s harder than ever to find the actor behind the marketing machine.

A face-to-face interview is not always the most direct route. I once had a remarkable “phoner” with Meryl Streep. There was immediate chemistry, with laughter bouncing back and forth, and after our allotted time was up, she just kept on talking—Meryl merrily yakking about this and that until finally I had to cut the conversation short: I didn’t have all day. The next time we talked was at a junket in Montana to promote The River Wild. It was a pristine setting, on a lake ringed by mountains. But it was late, Meryl was spent, and as she talked for the umpteenth time about how women read rapids better than men, and how she got thrown from a raft and sucked into a hole, she looked right through me.

Another time I once spent 2½ hours interviewing Jack Nicholson, a luxury that now seems preposterous. By then I wasn’t just doing the stars, I was collecting them, and Jack was a trophy interview, one who required an elephant gun. John Updike once called celebrity “a mask that eats into the face.” But unlike Ford, Nicholson didn’t fret about that; like the Joker, he was too busy enjoying the meal.

It was 1990. We met at his office on the Paramount lot where he was finishing The Two Jakes, his laborious sequel to Chinatown. Four days into a fast to lose weight, Nicholson chugged water, chain-smoked Camels and talked circles around himself, often making no sense. It was more of an audience than an interview. At one point, when I tried to redirect a line of questioning, his eyes narrowed into crocodile mode. “I don’t necessarily want to give you the interview you want,” he said in that familiar desert-dry drawl. “I want to give you the interview I want.” But I tried to take him on. After he declared the white male to be the world’s only real minority, we got into an argument about money. He insisted wealth doesn’t change your life, and after pocketing $50 million for Batman he presumed to be an expert.

“You probably think if you had $150,000 it would solve your problems,” he said.

“I could get a year or two out of it. Write a novel. Pay the mortgage.”

“I bet that don’t cover your mortgage. And writing a novel, I go with Nietzche. If you don’t want to write it in your blood, save us the space. I’m the only modern writer of my generation. I do it without paper. There are a tremendous amount of books I read where I think, this person knows me and my work.”

One of the privileges of being a Hollywood legend is that no one will tell you you’re crazy.

In his prime, Jack was a rock star among movie stars, a satanic majesty ruling Hollywood from his aerie on Mullholland Drive. But actual rock stars are another species, and among those who are not dead, none is more iconic than Mick Jagger. For a journalist who grew up as a Stones fan, he was the Everest of interview subjects. By the time I met him, the idolatry phase was long gone. But that summer afternoon in 1994, a day at the office for him was still a monumental event for me. We sat in an empty classroom of a Toronto school where the band was rehearsing its Voodoo Lounge tour in the gym. He seemed strangely diminished in the flesh. Pale, impossibly slight, a concave chest peeking through an untucked pink shirt, an indolent youth in old skin.

Jagger never says much in interviews. Unlike his cohort Keith Richards, who rolls out soundbites like the ancient Mariner, he deflects questions with sly diffidence. (“The Rolling Stones are a rock band. They make records and they go on tour. You can’t really expect them to do an awful lot more than that.”) But how he says what he doesn’t say eludes transcription. Watching him talk, I kept getting lost in his face, a quicksand of compulsive gestures that seemed to have a mind of its own. Later when I listened to the tape, all the meaning lay buried in the inflection, lazy arabesques of innuendo from a man tired of his own cliché. You could hear the words melt away in his mouth, consonants turning to rubber, vowels stretching like taffy. He sounded like a harmonica. Which is to say, you had to be there.

By contrast, perhaps because she was young and intellectually insecure, a superstar craving credibility, Madonna crisply answered every question like a schoolgirl trying to score an A. She chose her words carefully, as if crafting an essay, saying more than once that she didn’t want to sound stupid. Despite being a pop idol with millions of fans, she felt only a handful of people understood her art. As she dished about Sean Penn’s new baby, Warren Beatty’s penis size and God’s bisexuality, it was all wonderfully clinical.

At a certain point it seemed polite to stop asking questions. Madonna unclipped the microphone, let out a long sigh, then leaned back on the divan, baring her midriff. I decided to push my luck and ask for a tour of the house. It ended in the bedroom: a white bed, a stuffed cat on the pillows. “It’s a good throwing cat,” she said, hurling it to the floor. Before leaving, I asked Madonna for a photo of us to run on the editor’s page. She wasn’t made up for the camera, but agreed, as if she didn’t have the power to refuse.

One way to avoid being intimidated in a star’s presence is to overcompensate, and I handled Madonna with a nonchalance that bordered on indifference. We never uttered each other’s names. She didn’t flirt or express some token curiosity about my life as some stars will. Which was just fine. I was not a fan.

When you are a fan, an interview comes as a mixed blessing, an end of innocence. In a rare case, you may strike up some kind of relationship, which I’ve done over the years with Leonard Cohen. But then Leonard handles interviews with the same loving sanctity he brings to everything else; if the journalist is female, he may offer to draw her a bath.

Interviewing Mick was strangely distancing, because it felt too comfortable, especially the second time. Once in Cannes I spotted him at a party for Trainspotting. He was standing in a corner talking to friends, twitching to the music. Seeing stars in the wild is different than in the media zoo. Like anyone, I still get a kick out of it, and wonder if I dare bother them. Eventually I did approach Jagger. I’m a journalist, I thought. I have a right. A duty! Thankfully, he remembered me. We asked each other what we were doing in Cannes. We chatted about movies. It was brief, pleasant and shatteringly normal.